For all the blustering about trade wars, the fact is that Donald Trump’s punitive actions against China during his presidency didn’t do much to hurt its economy. But it’ll be a very different story if he wins in November and makes good on his pledge to slap tariffs up to 60% on Chinese imports.

Group Chief Economist Neil Shearing talks to David Wilder in the latest episode of The Weekly Briefing about what Trump 2.0 might mean for China, and how fresh trade actions could exacerbate the forces that are fragmenting the global economy. Neil also explains what lies ahead for this stock market bubble in the wake of that Nvidia earnings report and previews the coming week’s key inflation data for the euro-zone and the US.

Also on the show, Asia-Pacific Head Marcel Thieliant and Senior Markets Economist Tom Mathews discuss what the stunning rebound in Japanese stocks says about its economy and Ariane Curtis from our Global Economics team introduces the Long Run Economic Outlook, our unique, in-depth look at the world to 2050.

Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 23rd of February and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, what next for Japan stocks after they finally crawl the way back above their 1990 high and an exclusive look at our long run global economic outlook. But first, Neil Shearing Group Chief Economist is with me to walk over the week gone by and anticipate the big events in the coming five trading days. Hi there, Neil.

Neil Shearing

Hi, David.

David Wilder

I wanted to start by asking you about the Franco -Prussian War. Kidding. It's got to be about inflation central banking, doesn't it?

Neil Shearing

I'm afraid so. We're back to inflation. We're back to monetary policy.

David Wilder

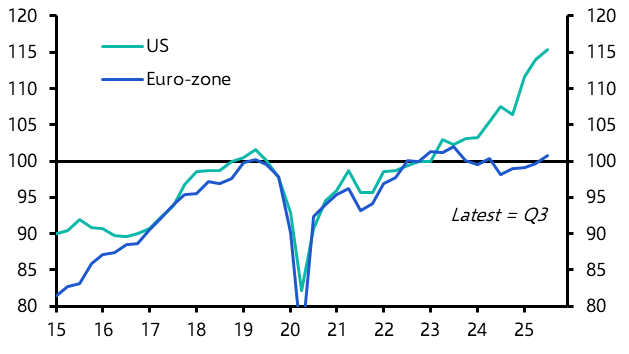

One day inflation will be back at target and rates will be neutral and we can talk about Bismarck. But this is not that day, is it? We've got Eurozone and US inflation data in the coming week. It's all coming as rate cut expectations are being pushed further into 2024. Central bankers for the most part seem to be telling markets to cool their boots. Let's start with the Eurozone data haul because our Europe team has been tracking signs that services inflation is looking a bit sticky. Is that a risk for the coming week's release, do you think?

Neil Shearing

Well, I think it certainly is a risk. It's the key part of the release that we're going to be keeping an eye on. I mean, for what it's worth, we think that both headline and core inflation in the eurozone are going to come down. So you've got headline inflation down to two and a half percent in February in next week's release and core inflation down to three percent. Energy inflation goes up, that's more than offset by falling food inflation. And then you're right, there's the core part, which is obviously the part that the ECB is going to be most focused on. And there are some signs that the falls in core inflation have been slowing and perhaps service inflation has become a bit stickier in recent months. Now, to some extent, that's not the big surprise. Obviously, core inflation has come down a long way. Like I say, it's back at kind of 3 % and we still think it's going to fall further. So some of those factors that have pushed up services inflation, I don't think will persist, but it's clearly, as you say, rattled a few on the governing council. We've had a few speeches over the past week or so pushing back on the idea of rate cuts in April. And it's now the case that I think markets are pricing a less than 50 % chance of an April rate cut. We'll be publishing our ECB Watch, which is the publication in which we preview the forthcoming ECB meeting in the coming week. We'll take a view on April's meeting there. For now, we think it's probably too soon to completely rule out an April rate cut, given weakness in the real economy, of course. German recession confirmed in some of the GDP data over the past week or so. And given the fact that we think core inflation has got further to come down, it's probably a bit too soon to rule out an April rate cut still.

David Wilder

What about US PCE? This is the inflation series that the Fed watches. The next release is out this coming Thursday, comes on the heels of that massive January payrolls number and the hot CPI reports for January. What's this week's release going to do to expectations for that first rate cut, do you think?

Neil Shearing

Yes. Now, first point is that this is PCE data for January. We've got the inflation data for the eurozone is for February. This is for January. So that's the first point to make. The second point as it relates to the US is that it's PCE that the Fed looks at rather than CPI. And in particular, it's core PCE. So that's the number to be watching for and paying attention to. It increased by 0.24 % in December. We think it's going to increase by 0 .35 % in January. That 0.35 % of course is important because it gets rounded up to 0.4% and I suspect if that's the number, it might send a few more shockwaves and few more jitters through bond markets. And it will reinforce this narrative that inflation or rather the disinflation process has stalled. When you unpack exactly what's going on under the hood, I think there are fewer reasons to be concerned. A lot of the increase in PC, core PC that we're anticipating in January is about stronger gains in healthcare services and portfolio management charges that are linked to a strong stock market rather than factors that are necessarily driven by the underlying strength of demand in the economy and underlying price pressures. So perhaps less to be concerned about when you dig into the data than the headline number might suggest for Core BCE, but I think it could be another week in which the inflation data start to unsettle bond markets.

David Wilder

Let's look further ahead. Let's look past these inflation releases, look past central banks and hone in on November's US election because we're continuing to add to our analysis of what this election could mean for the global economy. This past week, we've had two major pieces of work on aspects of that, the global macro risk, the market risks around that. The latest looks at what could happen if Donald Trump is re-elected and makes good on his tariff threats that he's making on the campaign trail. Looking at our report and some of the election polling data, it would be hard not to conclude that on the economy at least, Beijing must be pretty nervous about his re-election.

Neil Shearing

Yes, that's right. I mean, actually, when you look at the effect that the first round of Trump tariffs had on China's economy in the 2016-2020 presidency, it's pretty difficult to ascertain there's any effect at all really. Now, there's a couple of reasons for that. One is that the impact of tariffs on China's exporters was offset partially by a weaker renminbi, but also we saw some routing of exports through third party countries as well. So that helped to kind of mitigate the effects of tariffs on China's export base. I think this time will be different and it'll be different for a couple of reasons. One is that the scope of the action that is being proposed by Trump at this stage looks larger. Of course, he's the presumptive nominee and he has to in election two, so we shouldn't assume that he's going to be the next president. And what's more, policy has often changed from what I discussed on the campaign trail. But nonetheless, what he's talked about so far, 60 % tariff on Chinese goods, for example, looks much bigger in scope and size than we've seen previously. In order to fully offset the effect of that tariff, the renminbi would need to fall to something like eight and a half against the dollar, our estimates suggest. And I think it's difficult to envisage.

slide in the currency on that scale, given the destabilising effects that it would risk. So that's the first point. The scope of the tariffs and action proposed by Trump seems to be greater and the scope for the currency to offset that is smaller. I think the other point is that the nature of China's economy has shifted over the past three, four years. In particular, we've seen large investment in China's manufacturing base, particularly during the pandemic. We've also seen China's trade surplus, current account surplus, rebound as a share of global GDP over the past couple of years. So it's now much larger than was the case in 2016, 2017. Now you won't get that by looking at Chinese trade data. When we use the Chinese customs data, which takes account of the fact that a large chunk of Chinese exports increasingly go through what are called bonded trade zones and therefore don't appear in the Chinese balance of payments data, the Chinese trade surplus looks a lot larger. So China's invested a lot in manufacturing capacity. Its trade surplus with the rest of the world has already rebounded a long way. And now there are concerns, not just in Washington, but also in Europe, about Chinese firms dumping manufactured goods on the rest of the world because they have this excess capacity. So I think that the geo-economic and the geopolitical context has moved on a lot in the last four or five years.

David Wilder

Putting all that together, what does this mean in terms of global fracturing or fragmentation as the IMF calls it? How does this fit into that narrative that we've been following the past few years.

Neil Shearing

Now we spent a lot of time over the past couple of years, including on this podcast, talking about small yards and high fences when it comes to US China fracturing. The small yard being a small area of bilateral trade or investment flows affected by controls, but the high fence being the fact that those controls are very strict and stringent. So large amounts of US China trade and investment flows don't really get affected by fracturing, but those aspects that are affected by fracturing, for example, chips and batteries and advanced manufacturing and biotech, the controls in those areas can be very stringent and the effects of those controls can be wrenching. One of the issues though is that we have never really defined just how big that small yard is and what's included in it. And I think one of the dangers or risks with say a 60 % unilateral tariff on Chinese goods proposed by Trump is that unintentionally, that yard becomes much larger. So we move from a situation where we have a small yard and a high fence to a larger yard, but still a high fence. So we unintentionally perhaps expand the scope of US -China fracturing to include a much larger number of areas.

David Wilder

The other big piece that we had on Trump this week all about his impact on financial markets, as big a splash as his policies could cause, I think that piece concluded it wouldn't be enough to burst this AI-driven stock market bubble. I mean, that's key, isn't it? This is a tech -driven market bubble like railways, like the internet before it. Given we've had these Nvidia earnings as well this past week, talk a little bit about market bubbles and the development of technology like AI.

Neil Shearing

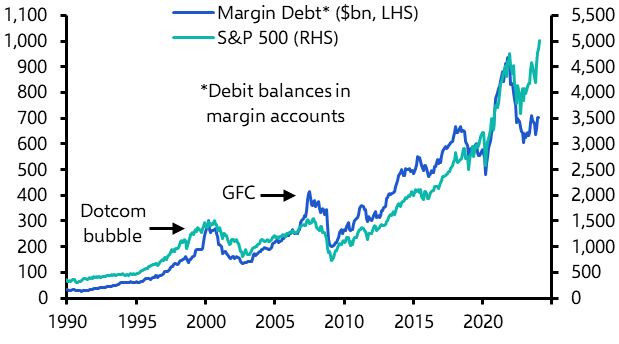

Well, I think one of the big differences this time around compared to previous episodes is that actually the tech companies that are at the forefront of the AI revolution are hugely profitable and hugely cash generative. So if you think about the tech stocks that inflated during the dot -com boom of the early 2000s, often many of these companies were kind of loss making. Whereas we've just seen, as you say, in videos results, huge revenue growth, huge profit growth. And the same is true of the other magnificent seven. So I think the context is slightly different. However, if we look at conventional measures of valuation, it does look pretty stretched in the tech space look at price earnings ratios, they look stretched. If you look at measures relative to other valuations, so for example, valuations of equities relative to bonds, it looks stretched too. So I think this probably is the early stages of a bubble, notwithstanding the fact that these companies are profitable. And there are lessons from history here. You're right that it is common for bubbles to inflate around new technologies. However, one of the other lessons from history, as Keynes says, is that bubbles tend to inflate for a lot longer than one can stay solvent. And if you look at the measures of valuation as stretched though they are, they're nowhere near as stretched as they became at the height of the dot com bubble. So my sense is yes, this is a bubble that's starting to inflate, but on balance, it's probably got a lot further to go.

David Wilder

Neil Shearing there on market bubbles, Trump versus China and our inflation previews for the coming week. I'll add our US elections page to the podcast notes. It's the gateway to our growing body of analysis on the macro and market risks around November's vote. On bubbles, I'll add a note by John Higgins, our chief markets economist, which explains why this bubble is different, what that means for the market outlook. All of this analysis is available as part of a subscription to CE Advance, our premium platform. Learn more at capitaleconomics.com. Staying on markets, Japan's Nikkei 225 index finally hit a new record high this past week, overtaking the previous record set 34 years ago. The performance of Japanese stocks has been helping fuel talk that the country's economy and its industrial base has finally turned a corner after a decades -long hangover from its debt binge. I spoke earlier to Marcel Thieliant, our Asia-Pacific head and Senior Markets Economist Tom Matthews about whether there's anything to the hype around the rise in Japanese share prices. Here’s that conversation now.

David Wilder

Hi Marcel. Hi Tom.

Marcel Thieliant

Hi David.

Tom Mathews

Hello.

David Wilder

Marcel, I'd like to start with you. What we're seeing in the stock markets, to what extent does this reflect a fundamental shift in perceptions around Japan Inc?

Marcel Thieliant

Well, there's definitely been a narrative that there has been a fundamental improvement, particularly in corporate governance that explains the recent strength in the stock market. And if you look at indicators of corporate governance, they certainly have improved. So the TOCA Stock Exchange compiles an annual yearbook with lots of indicators and they pretty much all point to in the right direction. The key problem though is that it's a bit more difficult to see that on the ground. So if you look at the profit margins of Japanese firms, Japan ranked in the middle of the pack among G7 countries on the eve of the pandemic, but its profit margins are now the lowest in the G7. So it's a bit difficult to argue that this improvement in corporate governance is having any real effects on corporate behavior. I think what's less appreciated though is the fact that higher inflation could actually be quite positive for the stock market. Now in principle, if you have high inflation, you should also have a higher discount rate. So it's not necessarily positive.But the Bank of Japan obviously has kept interest rates at close to zero and long -term interest rates also haven't risen all that much even as the Bank of Japan has loosened its grip on the bond market. So if you think that inflation in the long run will be much higher than it was before the pandemic, that is definitely a positive for the stock market and could explain some of the strength that we've seen recently. I think the main problem though is that investors are conflating cyclical strength in corporate earnings mostly driven by the very weak yen with a structural improvement. So the weaker yen boosts corporate profits in basically through channels. The first is through export earnings. Now, Japanese firms mostly price their exports in US dollars and price them to market, which means that they don't typically adjust those prices very much. So weaker yen basically boosts the yen value of those foreign currency imports, exports, but more importantly, Japanese firms earn a lot of money from their overseas subsidiaries and those earnings are worth one to one more in yen if the yen weakens. So a lot of the strength in corporate profits that we've seen over the last couple of years is simply down to the weak yen. And once the yen does start to strengthen as overseas interest rates fall back again, that tailwind will turn into a headwind.

David Wilder

Tom, tailwind to headwind – talk a bit about the yen in driving these stocks and talk a bit about where we see the yen going over 2024 and obviously implications for Japanese equities.

Tom Mathews

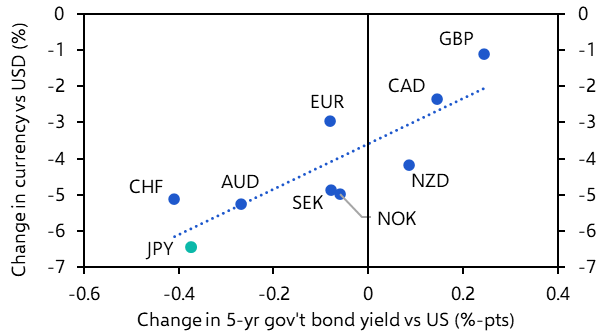

Well look, I mean to start with, we see the yen quite a bit stronger over the rest of this year. So we're forecasting 130 to the dollar. That's almost 15 % stronger than its current level of around 150. And there's a couple of reasons for that really. The first is where we see relative interest rates going. So it's interest rate differentials to the US that have been really the big driver of the weakness of the yen over the past couple of years. You know, we saw the Fed hiking really aggressively earlier on in this tightening cycle and of course the Bank of Japan not doing anything at all and in fact holding down yields with this yield curve control policy earlier on as well. So that's where this huge interest rate gap opened up in favor of the US dollar relative to the yen. We're now starting to look at the other side of that cycle where the Fed is probably going to be easing later this yearwhere the Bank of Japan might actually start tightening. And in fact, we think that in particular that investors are underestimating how far the Fed will ease. And that's likely to push yields down in the US and in favor of the yen relative to the US dollar. And it's quite possible the Bank of Japan might actually put a little bit of upward pressure on yields in Japan too. So all that could be quite potent and could potentially give the yen quite a bit of a boost.

The second reason is we think the valuation of the yen is just really low. Things like it's a real effective exchange rate, for example, so looking at how it reflects relative prices to Japan's trading partners. On measures like that, it's basically as low as it's been in about 50 years. So you could see quite a big turnaround. Now that, as Marcel alluded to, would be pretty negative for Japan's stock market, essentially. So we're forecasting Japan's equities to fall quite a bit over the rest of this year.

That's solely because we think the strong yen will basically unwind some of their recent relative strengths. What we are forecasting also is that in dollar terms, they'll hold up a bit better, partly because of that yen strength providing effects returns to investors from overseas.

David Wilder

Remind us of what our forecasts are for Japanese equities. We forecast the TOPIC, is that right?

Tom Mathews

Yes, that's right. For the topics, we're forecasting 2,440 for the end of this year, so that is almost 10 % below its current level, as I said, really just reflecting the large rebound that we're anticipating in the yen relative to the dollar. And yes, you're right also that we do forecast the topics. Obviously it's the Nikkei at the moment that's got everyone's attention because it's the one that's retraced its all -time high, whereas the topics is still slightly below its own mark on that basis. But the topics, of course, as listeners will know, is the market cap weighted index, the more modern one that I think is probably ultimately more relevant for investors than the somewhat old -fashioned Nikkei.

David Wilder

Marcel, I want to bring you back in. You've spoken about inflation, obviously touched on the BOJ, but just to give us a bit more on this. So you're forecasting an April rate hike from the BOJ. You've just published a note talking about how the BOJ has succeeded in creating a high pressure economy. Talk about that in terms of the BOJ policy outlook. Have they finally slain deflation?

Marcel Thieliant

You could actually argue that they had this slain deflation before the pandemic already when inflation averaged about half a percent. But I think what they may have finally achieved is actually meeting their 2 % inflation target. I mean, a lot of the strength in inflation that we saw over the last couple of years was simply driven by the weak yen and sorry, import costs. But they're now mounting signs that domestic inflation is picking up. So this is what the bank Japan likes to call the virtuous cycle between wages and prices.

So wages are basically rising in response to higher prices as employers seek compensation for the fall in real wages. And that is, at the moment, this cycle is probably strong enough to meet the 2 % inflation target, but not more than that. So we think that the Bank of Japan will now use the current window of opportunity to end negative interest rates, to also end yield curve controls, so basically end the most distortionary and the most extraordinary policy measures that they have in place. We don't think there's a case for outright fighting monetary policies. Once that has happened and as the yen starts to strengthen the second half of the year, bringing down imported inflation again, we think that the Bank of Japan will just stay put for the foreseeable future.

David Wilder

Tom, finally, I can't let you go without asking an AI related question. We're talking just hours after those Nvidia earnings were out. AI at the tipping point, says CEO Jensen Huang. What does AI mean in terms of Japan stocks?

Tom Mathews

Look, I think it's definitely been on net positive for Japan's stocks. We've seen since AI enthusiasm, if you like, started to grow around the middle of 2023 that Japan's stocks have done well. And of course, as we've discussed, the last part of that is the weakness of the yen. But I think they have benefited from enthusiasm about AI as well. So they've lagged maybe the US, which is really the center of this technology and the center of this excitement among investors about that. But they have actually fared better than a lot of other benchmark indices like Euro stocks, for example, or the FTSE or Canada’s TSX Composite as well. So other indices are actually Japan does seem to be doing a bit better and maybe benefiting a bit more from that investor enthusiasm. And we saw that again today with a decent boost from those Nvidia earnings for Japan's equities as well. So I do think they stand to benefit from that sort of enthusiasm. They're seen as being maybe a bit closer to the tech than some and benefiting in a bit from it a bit more than some, not as much as the US for sure, but certainly relative to some of those other benchmark indices. It seems like they stand to do well.

David Wilder

Will that imply that it's going to follow the same similar trajectory to what we're forecasting for US stocks in terms of bubble falling and then bursting and 2025-ish?

Tom Mathews

Yes, that's right. It's a bit more complicated by the big moves in the end. So if we're thinking about the topics itself, it's going to have that huge headwind. But if we're thinking about the performance of Japanese equities and dollar terms, then yes, absolutely, it should do quite well. Again, not as well as the US and our forecasts, but relatively well before, perhaps, deflating later on in the decade.

David Wilder

That was Tom Matthews and Marcel Thieliant on Japan's stunning market rebound. I'll post Marcel's note about how the BOJs created a high pressure economy on the podcast page as well as some recent analysis on the yen outlook from our FX Markets team. Watch out for our coverage of that BOJ April decision. There'll be lots of analysis about the macro policy and markets angles in the leader on the day and in the aftermath and Marcel and co will be doing a drop in. That's one of our short form online briefings on the day itself. Details to follow CE advanced clients get invites to all our drop ins as well as a host of other tools to engage directly with our economist team. Find out about our premium platform at capitaleconomics.com/ce-advance. Ariane Curtis from our global economics team will be participating in a drop in This coming Thursday, 29th of February, to talk all about the world economy to 2050. Ariane's the lead economist for our Long Run Economic Outlook, which is our annual report all about the forces that will shape the global economy in the coming decades. It's in-depth analysis coupled with extensive forecasts of key macro variables across DMs and EMs and this year's report focuses on the risks of protectionism, but also on AI as a driver of long term global growth. I spoke to Ariane about the report earlier in the week and I started by asking how important AI is going to be to the global outlook.

Ariane Curtis

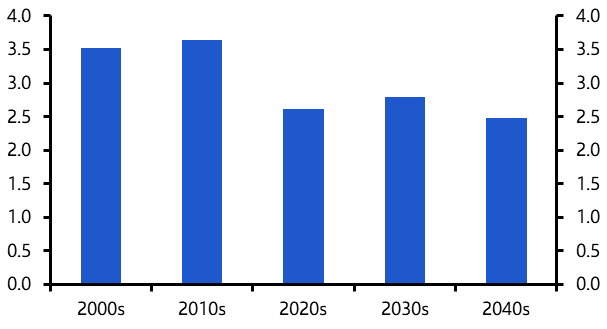

Yeah, it's going to be quite important, especially in advanced economies and within that, especially in the US. So if we're right, that AI is going to prove to be a genuine general purpose technology then we think we could see productivity gains pretty similar to what we saw in the US during the ICT digital revolution. We think the boom isn't going to happen immediately. It's probably mostly expected to come in the 2030s really, but that should lead to productivity growth in advanced economies averaging about 2 % in that decade versus the sub 1 % rates that we've become accustomed to in the past couple of decades. So yeah, quite important.

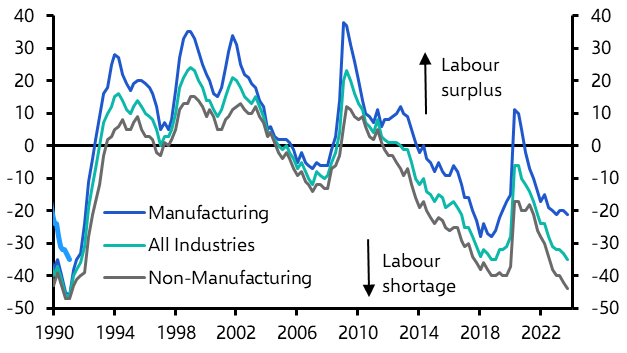

But as a counterweight to that, we have this long running overhang of demographics. You talk about this, what sounds like a very meaningful productivity boost from AI, but I think one point your report makes is that it's not going to be enough to counter the impact of aging workforces. Isn't that right? Yeah, certainly not in some cases. So if we look at, for example, in Italy, in Germany, in Japan, all of those countries are set to see quite significant declines in their working age populations in the coming decades. The demographic outlook is also pretty bad in some emerging economies, such as the Asian tigers. And in those cases, we think that the weaker demographics, as you say, will offset any of the gains from AI. But it's not the case in every country. In fact, we think that strong net migration in Canada and Australia, for example, together with the fact that both of those economies are pretty well placed to benefit from the AI revolution could explain why we expect growth to be the fastest among advanced economies actually in those two countries, even slightly higher than in the US.

David Wilder

So immigration as an answer to these demographic forces and this idea that actually, you know, aging workforces isn't just an advanced economy issue. You mentioned some emerging economies there. I wanted to get onto that actually, because I think one benefit of this report is it brings together these big picture themes that the economist team have been spending months, sometimes years, analyzing, presenting them in this coherent framework for thinking through what the global economy is going to look like over the long term. And this China view is a case in point. Obviously, lots of worry about China from a demographic point of view. But there's also a lot of attention at the moment on China's economy, the slowdown, the absence of meaningful stimulus and whether the government will push through enough stimulus. Your report makes clear that in the absence of fundamental reforms that China watchers have been waiting decades to see, the long -term outlook for the economy is a fairly grim one. In terms of the big macro picture, the big global picture, talk about where we see China going and what that means for the long term.

Ariane Curtis

Yeah, so as you say, we do expect growth to slow quite substantially in China, and that's really going to be quite a major drag on the global economy. So if we're right, that growth already in China is going to slow to about 2 % by the end of this decade and be even weaker by 2050. That's going to have a big bearing on the global growth forecast. So for example, that compares to growth in China of about 7 % in the past two decades. This is one of the reasons that we don't think China is going to surpass the US in the relative economic size. And it's actually barely going to gain any ground in the coming years. And since really China was one of the major engines of global growth since the financial crisis, the slowdown, as I said, is a major reason why global growth is going to slow over the coming decade. But all that being said, in the report, we do try to flag some of the key upside and downside risks, given that for long -term forecasts going such far out, of course, so much can change in the state of the global economy. And one of our key upside risks is that if state intervention in China was pared back and they allowed structural reforms to gather and pace, then this could really actually boost productivity growth could even potentially lead to China eventually overtaking the US if these reforms did have significant impact. So that would be, of course, a quite big upside risk to global growth if that were to materialise. But not our base case.

David Wilder

I wanted to end just talking about inflation and interest rates because obviously that is the big talking point of the moment. But I would like to look further out, look out towards 2050 once we get past this current post -pandemic burst of price rises and monetary tightening from central banks, what does the long -term future hold?

Ariane Curtis

Yes, I think we've tried to make the case in both this report and in our previous work on r* that really the era of ultra -low inflation and low interest rates in advanced economies is probably over. So all those kind of, some of these structural factors which weighed quite heavily previously on both of those, we think we'll go into reverse in the coming decades. So as I mentioned, AI is going to boost potential growth in economies. And given the ageing of populations, it's likely that desired investment relative to savings is also going to rise. And all of this is really going to push up on equilibrium interest rates. So equilibrium interest rates, which often are referred to as r*, we think will rise in the coming decades. And especially in the US. And so r*, our estimate of equilibrium interest rates, we think is going to rise from, you know, close to zero in the eurozone to about 1 % and a bit over that in the US to 2%. So, you know, we've not really seen equilibrium interest rates at this level in the post financial crisis era.

David Wilder

That was Ariane Curtis on the long run economic outlook. I will post a report on the podcast page. There's much more in there about demographics, economic fracturing and protectionism, as well as the inflation and rate outlook. I'll also add details of the drop in. Sign up to ask Ariane and the team your questions about the long term outlook in the live session or just register to get a recording of the session as soon as it's finished. But that's it for this week. We'll be back next week with our preview of the UK's spring budget statement, our deep dive into the outlook for carbon prices and Neil will be back talking central banks and inflation, bringing us up to speed on what's been happening and what we expect to see in the coming days, weeks and months. Until then, goodbye.