Last week we published ‘AI, Economies and Markets’, our in-depth report on the economic and market implications of artificial intelligence. The report and accompanying data painted a positive picture of the potential effects of artificial intelligence on productivity, economic growth and corporate earnings.

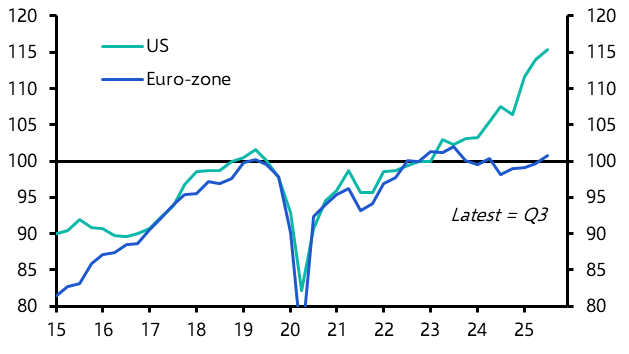

But it also made clear that some economies are far better positioned to reap the gains from AI than others, and that the process of adoption will cause enormous dislocation. Accordingly, while the US is likely to lead Europe and China in the AI revolution, there will be winners and losers within every economy. (You can read the full report here and register to join an online briefing with its authors on 5th October here.)

The AI revolution is one of several “megatrends” that will reshape the global economy over the next two decades. A second is climate change and the efforts to tackle it; and a third is US-China fracturing or, to use the IMF’s language, “geo-economic fragmentation”.

These megatrends are becoming increasingly prominent within market discourse and, indeed, form a growing part of our conversations with clients. The idea of peak globalisation was considered controversial when we first began talking about it more than five years ago. It has since entered the mainstream.

All of this is good for debate. However, three points are worth stressing when thinking about how these megatrends will affect economic and market outcomes over the coming years.

The first is that these trends are not fixed – they are fluid and will shift over time. Our report on AI is not the final word on this issue. Instead, it represents the start of a flow of analysis that we will continue to update as the technology – and social and political attitudes towards it – develop. The same is true of our work on both fragmentation and climate economics.

Crucially, while political shifts are unlikely to significantly reverse these megatrends, they will shape their evolution. For example, the US presidential election next year won’t halt US-China fracturing, but it will have a fundamental impact on the form that it takes. (A Trump victory would probably see a return to the transactional approach to trade policy that dominated between 2016 and 2020, and the increasing use of trade tariffs as an economic and geo-political policy tool.) Understanding how these shifts could play out is therefore critical to understanding their potential economic and market effects.

The second point to note is that, while there’s a tendency in markets to view these megatrends in isolation, in practice they are inherently linked and feed off one another. For example, the AI revolution is likely to become a new fault line in US-China fracturing – restrictions on technological transfers and exports of high-end chips and processors are not a passing fad; they are likely to become a permanent feature of the global economy.

Similarly, a key element of geo-economic fragmentation is likely to be a push by rival blocs to secure the minerals needed to fuel the green transition. This is one area where China appears to have a lead over the US. As climate change accelerates, it will become an area increasingly in focus.

More positively, advances made possible by AI may facilitate breakthroughs in green technology that in turn will help efforts to tackle climate change. Accordingly, investors shouldn’t just view these megatrends on their own terms – they also need to understand the linkages between them.

Finally, it is a mistake for investors to assume that, because these megatrends are long-term in nature, they are of little immediate importance. Markets are forward-looking and will seek to crystalise upfront any gains or losses that are likely to be caused by these megatrends.

Our report last week showed how the risks of a bubble in AI are something equity investors now need to factor into their thinking for 2024 – even if the technology’s economic benefits may not become fully apparent until the 2030s. Similarly, while it will take decades for the full macro effects of climate change to materialise, they are already affecting financial and commodity markets.

There are no easy answers here. These are each extraordinarily complex trends, made that much more complicated by their many interlinkages. These complexities in turn feed a temptation to look past them and focus more intently on short-term market moves.

But in doing so, investors risk leaving themselves unprepared not just to the challenges that these megatrends present, but also to their considerable opportunities. Our analysis doesn’t pretend to have all the answers to the questions posed by these trends. But it is designed to provide clients with frameworks for thinking through how they will shape economic and market outcomes now and into the coming years.

In case you missed it:

A last-minute deal to keep the US government open means the September employment report can be released on schedule. We expect the BLS to report a 170,000 increase in non-farm payrolls on Friday and provide more evidence of a cooling US labour market.

The US 10-year Treasury yield fell back a little last Friday after hitting another post-Global Financial Crisis high earlier in the week. Chief Markets Economist John Higgins explained in this recent note why we think it will fall much further before year-end.

Jennifer McKeown, our Chief Global Economist, previewed our forthcoming Q4 Global Economic Outlook in our latest podcast episode. You can see all our Q4 Outlooks on this dedicated page.