- We have just returned from three days of client meetings in Europe where the biggest topics of interest were US tariffs, Germany’s fiscal stimulus, risks to public finances (including in France) and our recent work on the future of Europe. This Update addresses these and some other key issues raised.

- Have we passed peak tariff uncertainty? Probably not. There are several potential flashpoints in the months ahead. The most obvious comes on 8th July when the original 90 day pause on reciprocal tariffs is due to expire. The 90 day pause on reciprocal tariffs on China will then expire on 12th August. The administration will not be able to conclude deals with every country ahead of the 8th July deadline and our assumption is that it will simply be extended for another 90 days. However, it is possible that the administration leaves it until the 11th hour before announcing any extension, which could trigger a fresh bout of market volatility.

- More fundamentally, while Treasury Secretary Bessant appears to be driving policy for now it is possible that trade hawks, including Peter Navarro, regain influence over the coming months. And while the US and China have agreed to reduce tariffs from punitive levels, fundamental differences between the world’s two largest economies remain. Finally, a lot boils down to the decisions of one man who is notoriously volatile. Our forecasts assume that tariffs ultimately settle around their current level and that as a result the damage to both the US and the global economy will be limited. But the path ahead will be a bumpy one and it is too soon to say that we have passed peak tariff uncertainty.

- Will there be a US-Europe “deal” on tariffs? There are a lot of plausible paths for EU-US tariff policy but we think the most likely outcome is a US baseline tariff of 10% on all imports from the EU. With that said, an agreement may take time. The US is not in as much of a hurry to reach an agreement with the EU as it was with China because markets have recovered in the past couple of weeks. And a deal will not be as easy to reach as with the UK because the EU and Germany run large trade surpluses with the US. So negotiations may run to the wire and the 90-day pause may be rolled over if no agreement is reached by early July. Meanwhile, we think the EU will continue to threaten retaliation but its actions will be very moderate as policymakers wish to avoid an escalating trade war.

- How much of a concern are deteriorating fiscal positions in advanced economies? The public finances of a number of major economies are on an unsustainable trajectory – but knowing if and when this might trigger some form of crisis, and what that crisis might look like, is extremely difficult. As it happens, the arithmetic of fiscal sustainability is relatively straightforward. Given assumptions about the primary budget balance (that is to say the budget excluding debt servicing costs), nominal GDP growth and government bond yields it is possible to construct a forecast of the public debt-to-GDP ratio over time. The problem is that each of these assumptions is subject to uncertainty and interdependencies.

- The critical component is government bond yields. As the UK learnt to its cost in 2022, movements in yields are driven as much by perceptions of fiscal credibility as they are fiscal policy itself. Of the major economies, we are most concerned about the US and France. The US matters because of the central role the dollar and the Treasury market play within the global financial system. Meanwhile, France’s position is complicated by its membership of the euro-zone and the fact that its central bank does not stand directly behind the country’s bond market. (More on this later.)

- Factoring a fiscal crisis into economic forecasts for either country is virtually impossible since it is difficult to identify the point at which the bond market’s patience will break and how governments in both countries will then respond. If the experience of the UK is anything to go by then pressure from the bond vigilantes may ultimately prompt a shift in policy that averts a full-blown fiscal crisis. From a macro perspective, the unsustainable trajectory of fiscal policy in the US and other countries is, on balance, a greater risk to the outlook than tariffs. But embedding this within forecasts is difficult.

- Is the dollar’s global position under threat? Concerns about the dollar typically conflate two things. The first is swings in its value and the second is speculation that its central role within the global economy is under threat. Forecasting short-term shifts in currencies is extremely difficult but assuming that tariffs ultimately settle at their current level and that concerns about America’s fiscal trajectory remain contained for now, we think that the dollar will stabilise and probably even appreciate a little over the next six months. Beyond this, the dollar’s position at the heart of the global economy is likely to continue not least because there is an absence of credible alternatives.

- The euro suffers from the lack of full fiscal and banking union and the internationalisation of the renminbi will be held back by China’s capital controls and high domestic savings and structurally large current account surplus. The value of the dollar will fluctuate over the coming years and on most measures it still looks a touch overvalued. But its special role within the global financial system is safe for now.

- How big a deal is Europe’s defence (and infrastructure) spending? The revision to Germany’s constitutional “debt brake” and planned fiscal stimulus should boost GDP growth in Germany itself to around 1% during 2026-2027 from its trend growth rate of around 0.5% per year. That will lift aggregate euro-zone GDP a little. But other euro-zone countries will be tightening fiscal policy and the aggregate euro-zone fiscal deficit will be little changed at around 3% in the coming years.

- Meanwhile, higher defence and infrastructure spending in Germany will have little impact on potential productivity growth. Most of the infrastructure spending will be on repairs to the existing transport network and municipal buildings rather than on new digital infrastructure. And very little of the defence budget will go towards R&D which could have commercial and productivity benefits. Further ahead, creating a self-sufficient European defence sector would have far larger effects on both Europe’s growth prospects and its geopolitical position. However, we argued elsewhere that Europe has neither the means nor the political will to undertake the extra spending and sustained co-operation this would need.

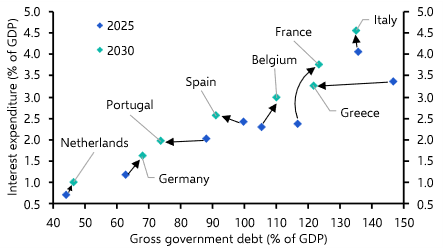

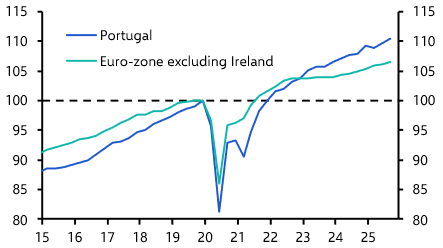

- How big are fiscal risks in the euro-zone? Systemic fiscal risks in the euro-zone are quite low because there are no major imbalances between core and periphery and because monetary policy is currently set at a broadly appropriate rate for the entire region. Moreover, the ECB now has the tools needed to prevent a problem in one country spreading via contagion in the bond markets.

- However, national fiscal risks remain elevated. Our euro-zone debt sustainability monitor suggests that these are greatest in Italy and France. In Italy, while public debt is very high, it looks likely to remain broadly stable over the next couple of years. However, we are increasingly worried about France, where the debt ratio is rising and the government has agreed only temporary measures to tighten policy this year. With the debt-to-GDP ratio set to continue rising, there may well be a loss of confidence in French government debt in the coming years. If so, the ECB would use its Transmission Protection Instrument to limit contagion to the rest of the region but would be reluctant to come to the aid of France itself so long as its fiscal position were unsustainable.

- Is Europe set for a period of reform and closer integration? Despite the optimism generated by the Germany fiscal decisions, hopes that there will be an acceleration of reform or major progress towards integration look misplaced. The Draghi Report on competitiveness outlined a blueprint for reform but there is no political will to push forward on capital markets or banking union. And progress towards fiscal union remains very slow: for example, the €150bn joint borrowing for EU defence procurement is less than 1% of euro-zone GDP.

Neil Shearing, Group Chief Economist, neil.shearing@capitaleconomics.com

Andrew Kenningham, Chief Europe Economist, andrew.kenningham@capitaleconomics.com

The Chief Economist's Note