Our meetings with clients in the Middle East and Asia last week took in discussion across a full range of macro and market issues, but the same three questions kept coming up:

How should we read China’s economy?

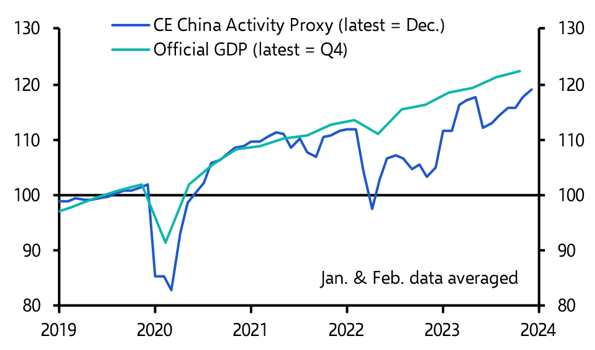

The conventional view is that China’s economy is extremely weak. However, while it is true that the recovery after reopening from COVID-19 restrictions ran out of steam relatively quickly, our China Activity Proxy suggests that in recent months the economy has regained momentum. (See Chart 1.)

That is not reflected in the latest business surveys, including the PMIs. But these surveys often reflect sentiment rather than conditions on the ground. Back in 2018, the PMIs fell sharply following the imposition of tariffs by President Trump, yet China’s economy remained relatively strong. Something similar seems to be playing out once again.

|

Chart 1: China Official GDP & CE China Activity proxy (2019 = 100, seas. adj.) |

|

|

|

Sources: CEIC, WIND, Capital Economics |

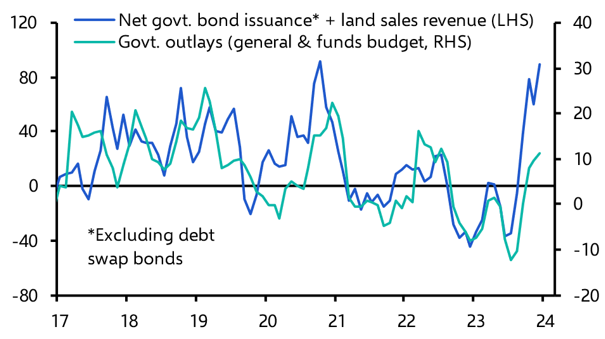

The pick-up in our China Activity Proxy is consistent with an increase in fiscal support since the end last year. As Chart 2 shows, the government has been raising revenues through debt issues and land sales. This is now passing through to increased public spending, which will support demand over the coming months.

|

Chart 2: Govt. Spending vs Funding from Borrowing & Land Sales (3m%yy) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

None of this means that China’s economy is a picture of health. It continues to face significant structural headwinds, including from the property sector. But conditions on the ground right now and not quite as gloomy as some of the headlines suggest. We expect the economy to grow by around 4.5% in 2024, an improvement over the 4.1% growth averaged during the previous two years.

When will inflation in the US and Europe return to target?

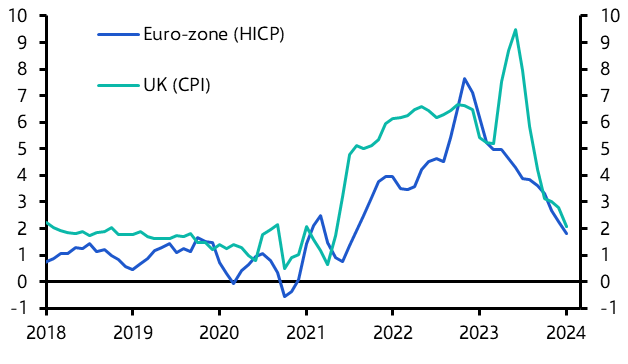

The short answer is that inflation may already be close to target in the major advanced economies. Admittedly, in year-on-year terms, both headline and core inflation remain elevated. In the US, core PCE inflation is currently running at 2.8% y/y. In the euro-zone, core CPI is currently running at 3.1% y/y.

But in Europe high annual rates of inflation are being driven in part by large monthly price increases in the first half of last year. More recently, month-on-month price increases have collapsed. The 3m/3m annualised rate of core inflation is now at or very close to 2% in the euro-zone and the UK. (See Chart 3.) And while the 3m/3m annualised rate of core PCE inflation rebounded in the US in January, this was due to one-off factors that we expect to fade over the coming months. We think core PCE inflation will be close to its 2% target by the middle of the year.

|

Chart 3: Core Inflation (3m annualised % change) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

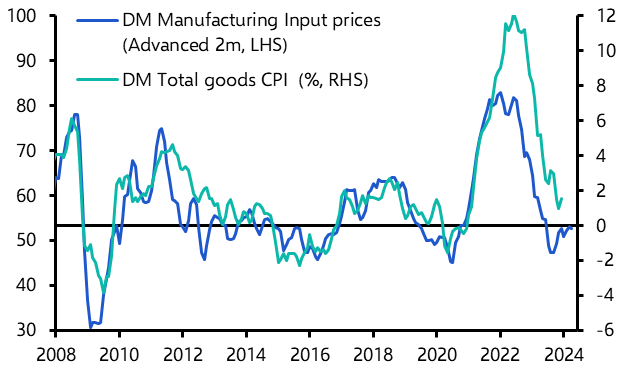

There are legitimate concerns about whether these falls in inflation are sustainable. One source of risk stems from dislocation to supply chains caused by disruption to shipping lanes through the Red Sea. However, while there is some anecdotal evidence that firms are facing a shipping-related rise in import costs, the pick-up in the prices paid balance of the manufacturing PMI has so far been modest. It is consistent with goods inflation in advanced economies of roughly 0% over the coming months. (See Chart 4.)

|

Chart 4: DM Mfg. Input Prices PMI & Goods Inflation |

|

|

|

Sources: S&P Global, Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

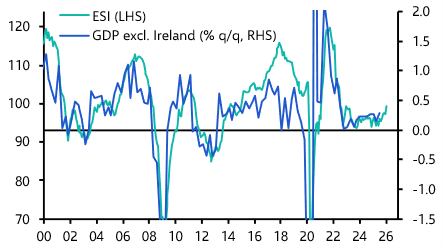

Another source of potential inflationary risk comes from tight labour markets. However, while unemployment remains low, other measures suggest that labour market conditions are cooling. Both vacancies and hiring intentions have decreased. Meanwhile, the fall in the quits rate is consistent with wage growth slowing to 3% or so in the US over the coming months. (See Chart 5.) Given the recent strength of US productivity growth, that would arguably be consistent with sub-2% inflation.

|

Chart 5: US Voluntary Job Quits & Wage Growth |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Central bankers will continue to talk tough but there is growing evidence that inflation may now have been tamed. Interest rate cuts should follow.

What would Trump’s re-election mean for global trade – and for China in particular?

The tariffs imposed by Donald Trump had surprisingly little impact on global trade flows. Despite President Joe Biden having kept those tariffs in place, US imports are now running at a record high while last year saw Chinese exporters ship goods in record volumes. Several factors have blunted the impact of Trump’s punitive actions: trade has been routed through third party countries; enforcement has been weak; and a fall in the renminbi has helped Chinese exporters maintain price competitiveness.

But there are a number of reasons why the effect of any future additional tariffs could be more significant. For a start, the size and scope of tariffs floated by Trump on the campaign trail are much larger. The threatened 10% tariff on all US imports and tariffs of 60% on imports from China would be much harder to cushion with exchange rate adjustments. We estimate that the renminbi would have to fall to 8.5/$ from around 7.2 now – a drop which would be politically difficult for Beijing to stomach.

More fundamentally, global trade imbalances have widened substantially over the past couple of years, an issue that has flown under the radar and which significantly complicates the picture.

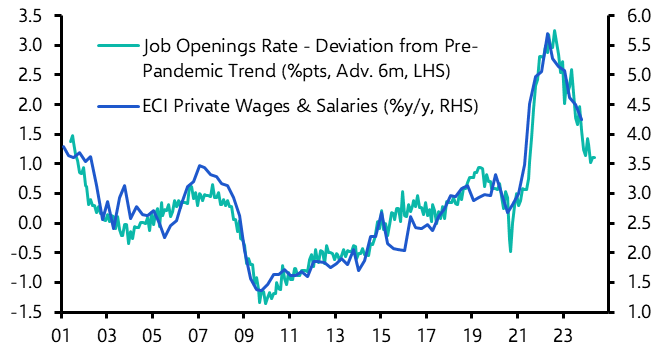

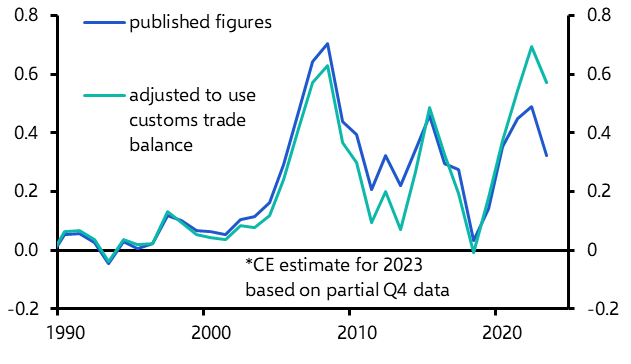

According to its balance of payments data, China’s current account surplus has risen as a share of global GDP in recent years but remains below the peak seen in the late-2000s. However, Chinese customs data, which includes exports routed through offshore trade zones and bonded warehouses, shows a current account surplus now close to a record high as a share of global GDP. (See Chart 6.) This reflects the large expansion of Chinese manufacturing capacity during the pandemic, which is now being pumped into overseas markets.

|

Chart 6: China Current Account Balance (% of World ex-China GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: CEIC, Capital Economics |

The upshot is that while Trump’s trade war aimed to narrow global trade imbalances, they have actually widened since 2018.

Accordingly, no matter who wins this year’s election, the US will come under increasing pressure to act against China.

In case you missed it

China’s National People’s Congress starts tomorrow in Beijing and this guide tells you about the targets and policy signals to watch for. Join our China team tomorrow for this 20-minute online briefing about what we’ve learned on the first day, but also why the NPC isn’t the cure for the Chinese economy’s ills.

We’ve pushed back our forecast for the first rate cut from the ECB to June at the earliest from April, and trimmed our expectations for cumulative tightening this year to 100bps. More in our preview of Thursday’s policy meeting.

We think Friday’s February US employment report will show a strong 250,000 rise in jobs but also see wage growth slow to just 0.1% m/m.