An intense flurry of diplomatic activity last week laid bare the fault lines of a fracturing global economy. In the Middle East, Joe Biden, Olaf Scholz and Rishi Sunak made separate visits to Israel to show their support for the country following Hamas’s surprise attack earlier this month.

In Beijing, Xi Jinping hailed his “deep friendship” with Vladimir Putin in their meeting on the sidelines of the latest Belt and Road Forum, an event at which leaders of emerging markets across Latin America, Africa and Southeast Asia extolled the centrepiece policy of Xi’s vision for a globally interconnected China.

There’s a temptation to view every shift in the geo-economic landscape through the prism of fracturing – or “geo-economic fragmentation”, in the IMF’s language. Certainly, conflict between Israel and Hamas and Hezbollah predates the end of this last age of globalisation, when the world economy started to be reshaped by increased US-China competition.

But this time is different. If nothing else, the question of China’s role is of greater importance than it was during previous crises in the Middle East. This is a result of Beijing’s efforts to position itself as a key actor in the region’s dynamics – an outgrowth of the country’s economic development but also its more assertive foreign policy under Xi. That approach was reflected in China’s shepherding of the Saudi-Iran rapprochement in March.

Fracturing goes mainstream

As geopolitical tensions increase, warnings about fracturing intensify. In 2019, when we were warning clients about the impact of a fracturing US-China relationship on the global economy, the IMF’s World Economic Outlook contained no references to “geo-economic fragmentation”. That started to change last year, when there were a total of eight fragmentation references in the WEO.

In this year’s outlook, published last week, the theme received no fewer than 172 mentions.

This increased awareness is a welcome and necessary development. As we argued in our 2022 Spotlight project, fracturing is a multi-year process which will fundamentally reshape the global economy and financial markets. With that said, mainstream analysis of this process still tends to get two things wrong.

The first is that the debate tends to overstate the likely economic damage from fracturing – and in the process misses important nuances that will be key to navigating a fragmenting world.

That isn’t to say that US-China fracturing will be without economic consequences. All things being equal, the path of global GDP will be lower in a fragmenting world than a globalising one because processes will have to be duplicated, cross-border flows of some capital and ideas will be subject to more friction and some businesses will find themselves operating in more uncertain operating environments.

But the scale of losses implied by some forecasts look excessive. The IMF, for example, estimates that global GDP could be 7% lower over the long term. That’s the equivalent of severing France and Germany from the global economy.

In our 2022 report on fracturing, we argued for the importance of understanding the drivers of fracturing in order to properly assess its potential economic damage. In our view, the principal cause is the return of geo-politics as an influence on policy decisions – and therefore on economic outcomes.

The prevailing view in the 1990s was that economic integration would lead to China and the former Eastern Bloc countries becoming what former World Bank Chief Robert Zoellick termed “responsible stakeholders” within the global system. But China has instead emerged as a strategic rival to the US. This rivalry is now forcing others to pick sides as the world splinters into two blocs: one that aligns primarily with the US and another that aligns with China. And policy choices within these blocs will increasingly be shaped by geopolitical considerations.

No deglobalisation

Viewed this way, there is no reason to think that fracturing will lead to a wholesale reversal of globalisation on the scale needed to create the economic damage that some fear. For example, there is no good geopolitical reason for the US to stop importing the vast majority of consumer goods from China. Indeed, for all the concern about fracturing, it’s striking that China’s export volumes have risen to record levels in recent months. (See here.) Likewise, our analysis showed how most cross-border flows of capital will be unaffected by US-China fracturing (See here.)

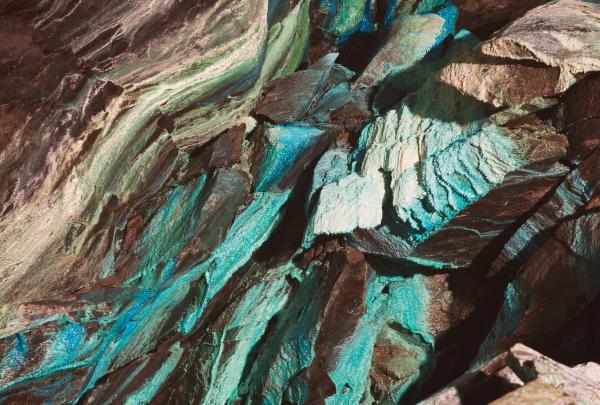

Furthermore, a focus on aggregate losses at a global level misses the crucial point that economic damage from fracturing will be distributed unevenly between the blocs. The global economy is not splitting down the middle. The leading economies, apart from China, are almost all close allies of the US. In contrast, economies that align with China are smaller and tend to be commodity producers. (See Chart 1. Clients can download our fracturing map and data here.)

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: World Bank, Capital Economics |

The economic size and diversity of the US bloc means it will be better able to adapt to the challenges posed by fracturing. Where production is moved for geopolitical reasons, it will relocate to other low-cost countries that align more closely with the US, such as India, Vietnam or Mexico. China, on the other hand, dominates its bloc and will struggle to find alternative sources of supply in those areas where access to US technology is restricted. For example, we expect China to face increasing difficulty in keeping pace with the rapid development of cutting-edge chips. The costs of fracturing are among the reasons we expect China’s potential growth rate to slow to 2% by the end of this decade.

Constant evolution

The second point that gets missed in the mainstream analysis is that fracturing is typically presented as being static in nature, whereas in practice it is a process that is constantly evolving. For example, while domestic political shifts won’t reverse fracturing, they will influence how the process develops.

Despite some expectations for a ratcheting down of tensions with China after the presidency of Donald Trump, the Biden administration has kept Trump’s punitive trade measures in place while broadening the scope of areas affected by fracturing by including restrictions on China’s access to cutting-edge US technology.

A victory for Donald Trump in next year’s presidential election would presumably lead to a return to the more transactional approach to foreign policy that dominated between 2016 and 2020, returning trade tariffs to the heart of the White House’s approach to fracturing.

At the same time, alignments between the US or China-led blocs are in constant flux. Saudi Arabia is notable here. When we first drew our fracturing map two years ago, we placed the Kingdom in the unaligned camp, but there have been signs that it is increasingly leaning towards the China-aligned bloc, reflecting both the ascendancy of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman and Chinese efforts to build alliances in the Middle East.

This alignment could shift again if Beijing’s ability to pull countries in the Middle East further into its orbit is challenged as the conflict between Israel and Hamas morphs, or if the Saudi-Iranian deal breaks down. Both could force China to take a more explicit position than it has done until now.

The key points that we continue to make to clients are that fracturing is an enormously complex and multi-faceted process and that they should be wary of efforts to boil down its global economic implications to any single-number cost.

It’s not enough that fracturing is part of mainstream discourse. As geopolitical tensions rise, it’s vital that investors understand the contours along which it will proceed.

In case you missed it:

Following on from our recent work on AI’s economic and financial market implications, Chief Property Economist Andrew Burrell explains what this technology will mean for the real estate industry.

Senior Markets Economist Thomas Mathews explains why the outperformance by Chinese sovereign bonds of their US counterparts and the underperformance of its equities against US stocks will soon end – and may even reverse.

A surge in migration into Australia isn’t easing labour shortages as much as hoped. Our ANZ team will be discussing how this will feed a final RBA rate hike in their Drop-In briefing following Q3 inflation data on Wednesday at 1100 SGT/1400 EDT.