- If the slump in China’s property sector continues for much longer, Australia’s export revenue would take a hit as iron ore prices tumble. But there are good reasons to think that the impact on aggregate demand would be smaller than many anticipate.

- Our China Service is the place for detailed analysis of the problems in China’s real estate sector. In short though, over-extended property developers are facing mounting headwinds as homebuyers boycott payments on unfinished homes and property sales slump. (See here.)

- Australia is one of the economies most heavily dependent on the health of China’s property sector. After all, iron ore exports to China were equivalent to 6.3% of GDP in 2020/21 and around 30% of China’s steel production ends up in construction. According to OECD estimates, 1.8% of Australia’s GDP was directly dependent on China’s construction sector in 2018, the latest year for which data are available.

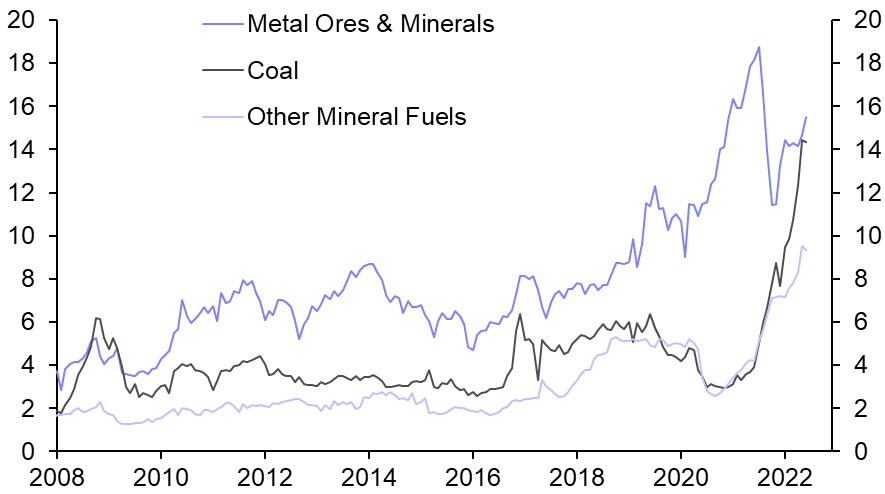

- However, there are two reasons why we wouldn’t necessarily revise down our forecasts for GDP growth even if China’s real estate sector continued to tumble. First, the surge in energy prices since the start of the Ukraine war means that Australia’s export revenue is now less strongly driven by movements in iron ore prices than at any point since the global financial crisis. The value of coal exports is now nearly as large as the value of iron ore shipments, while shipments of “other mineral fuels” (mostly liquefied natural gas, or LNG) have surged, too. (See Chart 1.)

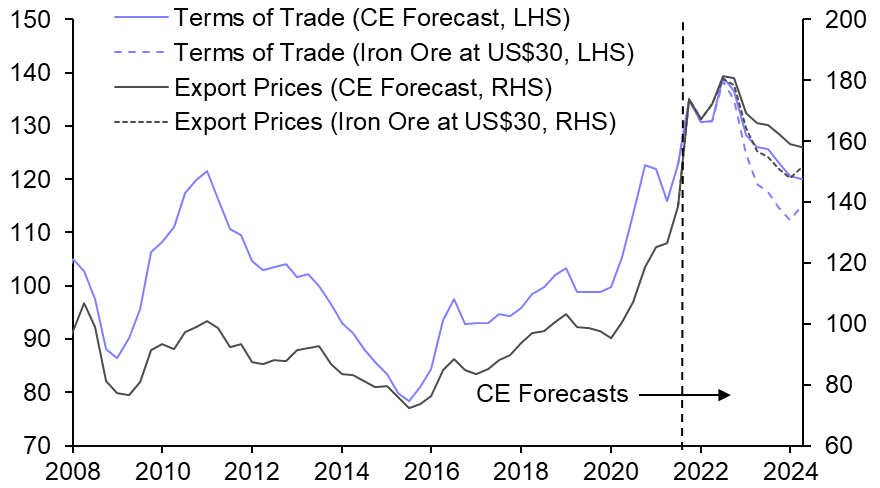

- With thermal coal and LNG prices set to remain high by historical standards, we expect Australia’s terms of trade to hold up quite well even as iron ore prices tumble. (See Chart 2.) The price of metallurgical coal, a key ingredient in steel making, has already plunged 60% from the record high in March. And we expect the price of iron ore to fall from around US$105 per tonne today to US$55 by end-2024. The only time in recent history that the iron ore price was lower was in 2015/16, when there were widespread fears of a hard landing in China. In a genuine real estate crash in China, the price of iron ore could fall to US$30 within one year and Australian miners would still make a small profit. Even then though, the terms of trade would still be higher than they were before the pandemic. (See Chart 2 again.)

- Second, the record high terms of trade are providing less support to aggregate demand than many believe. Mining firms have not responded to the surge in the prices of their output by ramping up investment in new mines. Mining investment was 2.6% of GDP in Q1, a far cry from the record high of 9.2% a decade ago. With investment subdued, mining output accounted for less than 10% of GDP in Q1 for the first time since 2015. And while miners’ capital spending plans for the financial year that started in July point to a pick-up, those spending plans aren’t any stronger than in the rest of the economy.

- To be sure, soaring commodity prices have provided a massive boost to mining profits, which accounted for more than half of corporate profits in Q1 for the first time ever. That in turn lifted corporate tax revenue by around 25% in 2021/22. But with the deficit in the underlying cash balance set to fall below 1% of GDP in 2022/2023, any renewed fall in tax revenue won’t prompt the government to tighten fiscal policy.

|

Chart 1: Australia Export Values ($bn) |

Chart 2: Australia Terms of Trade & Export Prices (Goods & Services, 2019/20 = 100) |

|

|

|

|

Source: Refinitiv |

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Marcel Thieliant, Senior Australia & New Zealand Economist, marcel.thieliant@capitaleconomics.com