Sometimes you can’t catch a break. Just as we received some good news on the global inflation front, problems in China’s economy have resurfaced.

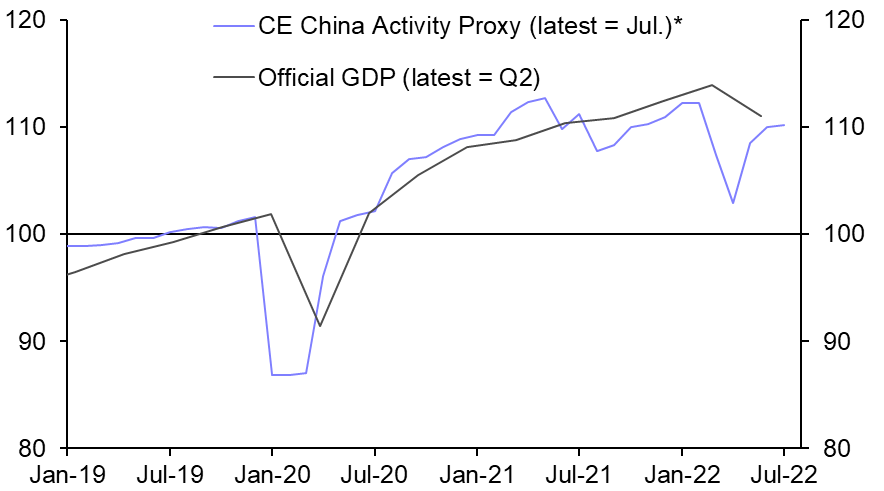

The big event last week was the release of July activity data from China – and it made for pretty gloomy reading. Retail sales, fixed investment and industrial production all slowed by more than expected as China’s post-Omicron bounce, which had been surprisingly strong in May and June, fizzled out. In response, the People’s Bank of China cut interest rates, a move suggesting that policymakers are becoming increasingly concerned about the outlook for the world’s second largest economy. Our proprietary China Activity Proxy (or CAP) pointed to flat-lining output last month. (See Chart 1.)

| Chart 1: Capital Economics China Activity Proxy & Official GDP (2019 = 100, seas. adj.) |

|

|

|

Sources: CEIC, WIND, Capital Economics |

Much of the current weakness in China’s economy can be traced back to problems in its property sector. At first sight, the parallels with the US in the mid-2000s look eerily similar. In both cases, a multi-year property boom led to a surge in house prices. And in both cases, booming activity caused the property sector to expand to account for an out-sized – and unsustainably large – share of the economy. (In China, property now accounts for about 20% of GDP.) What followed in the US is a well-documented cautionary tale for both investors and policymakers.

Developers are the weak link

In practice, there are important differences between the US in the mid-2000s and China today. In particular, Chinese households have much more housing equity. National regulators cap loan-to-value ratios at 80% and most cities set even higher thresholds. On average, buyers put down half the sales price as a deposit. China’s banks also appear to be better insulated from any problems in the property sector, not least because their state backing reduces the risk of contagion. Accordingly, a housing downturn is less likely to trigger the major disruptions in household and bank balance sheets that lay behind the 2007-08 global financial crisis.

Instead, China’s property problems are rooted in its over-extended developers, which are now struggling to meet their liabilities. China Evergrande has become a poster-child for the problems facing developers, last year becoming responsible for one of the country’s largest ever corporate debt defaults. But debt isn’t the only problem. Indeed, the majority of developer liabilities (~75%) are in the form of pre-sold homes that have yet to be finished. This reflects a feature of China’s housing market, where about 80% of homes are sold off-plan. The failure of developers to deliver these homes has led to mortgage boycotts, in which purchasers refuse to make payments on homes that they worry will go unfinished. That in turn has led to a tightening of financing conditions for already stressed developers. And it has also undermined housing market confidence more generally by highlighting the risk of buying apartments from struggling developers.

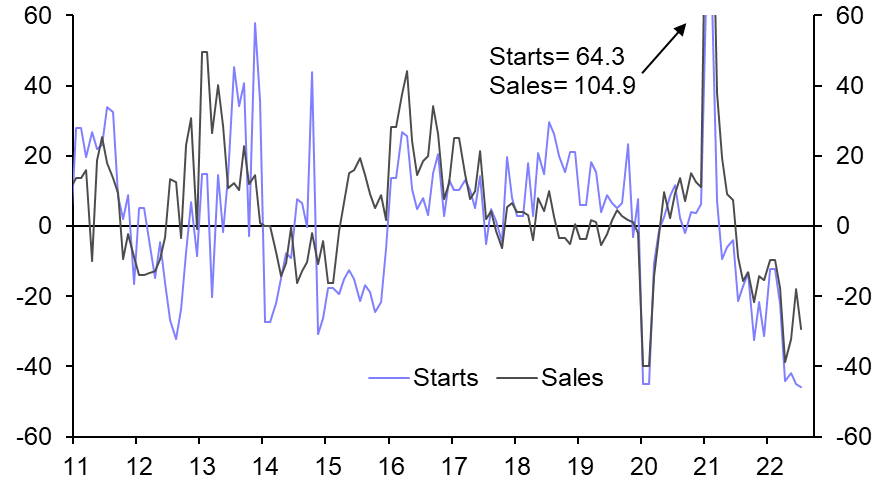

All of this has left China’s property sector reeling. Property sales fell by 29% y/y in July while new housing starts were down 45%. (See Chart 2.) It has also left China facing something akin to a liquidity trap; steps to loosen monetary and credit policy are unlikely to provide a significant boost to demand (particularly for housing) in the current circumstances.

| Chart 2: Real Estate Activity (% y/y) |

|

|

|

Sources: WIND, Capital Economics |

Charting a path forward requires sorting out the mess in China’s developers. The announcement last week that the government will underwrite the liabilities of stronger developers is a step in the right direction. But the real challenges lie with the weaker developers, and will be much harder to address. For a start, it will require someone – either the government, bond and equity holders, home purchasers or all three – to incur losses. According to our estimates, it could cost up to 7trn RMB (6% of GDP) to shore up the balance sheets of developers. And even if an agreement on how to allocate losses can be reached, any steps to backstop developers would conflict with a broader policy push against excessive risk taking in the financial sector. Resolving these issues won’t be quick or easy.

Even more headwinds

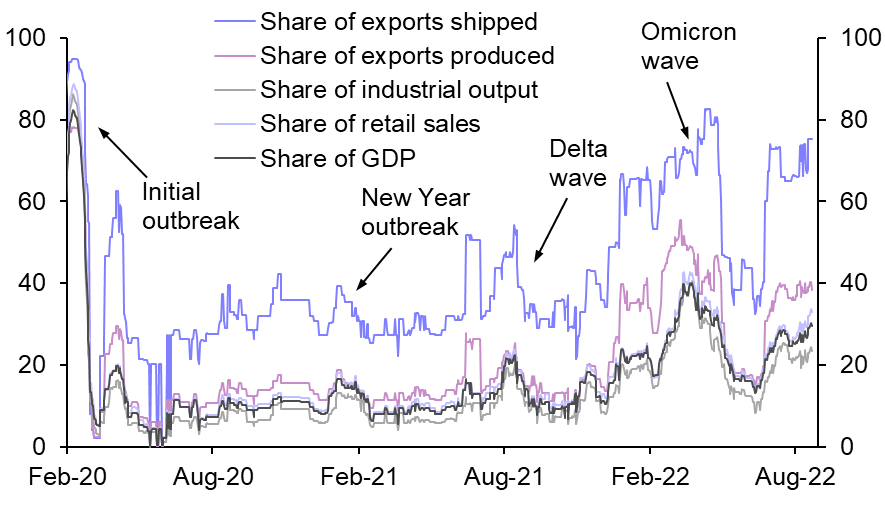

In the meantime, China’s property downturn is likely to continue. And if that’s not bad enough, the past few weeks have also brought bad news from other parts of the economy. First, a worsening drought in western China threatens to spark a nationwide energy crunch. Second, new COVID infections have risen to their highest since Shanghai emerged from its lockdown in May. More than 30 cities that together generate a fifth of China’s GDP are now undergoing local outbreaks. (See Chart 3.) Since the drive to vaccinate older, more vulnerable people has stalled, the government has little choice but to persist with its zero-COVID strategy. If a new wave of infections spreads, more lockdowns will follow.

| Chart 3: Share of Economic Activity from Areas Undergoing Local COVID Outbreaks* (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: CEIC, WIND, Capital Economics |

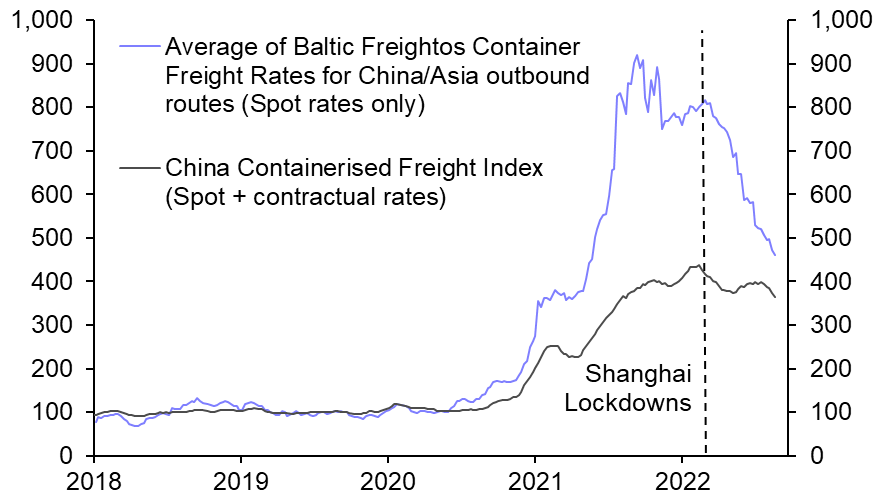

Finally, there are early signs that the export boom that propelled China’s recovery from the initial phase of the pandemic may be fizzling out as consumption patterns in the rest of the world normalise and inventories are rebuilt. Container freight rates out of China are tumbling. (See Chart 4.) The same is true of backlogs of work at manufacturers. A boom in exports has helped to mask deepening problems in other parts of China’s economy over the past couple of years. It now seems likely that over the coming months this prop to growth will be kicked away too.

| Chart 4: Container Freight Rates on China Outbound Routes (2018-19 Average = 100) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, WIND, Capital Economics |

All of this leaves the Chinese economy in a precarious position. The news on global inflation may be showing signs of improvement, but in its place we should expect more gloomy headlines from China. While we think its economy will stagnate this year, and post only modest quarterly growth rates in 2023, the consensus still remains too upbeat on the outlook. As signs of faltering activity pile up, expectations for Chinese growth could be in for a painful readjustment.

In case you missed it:

- Last week we held a drop-in for clients on the macro and market consequences of Europe’s energy crisis – you can watch on catch-up here.

- Our Senior Europe Economist, Jack Allen-Reynolds, argues that a shrinking construction sector will add to the headwinds facing the region’s economy.

- Finally, our Senior Markets Economist, Oliver Allen, assesses the prospects for different sectors of the stock market – and makes the case for defensive outperformance.