In a week in which UK and Japanese data both confirmed two consecutive quarters of contracting GDP, Group Chief Economist Neil Shearing explains why the concept of “recessions” can be unhelpful in understanding the state of economies.

He also tells David Wilder why, whoever wins in upcoming elections, governments on both sides of the Atlantic are likely to be shackled by fiscal constraints.

Plus, the most aggressive monetary tightening in a generation appears to have succeeded without breaking anything. Is the global economy off the hook or does financial instability still loom? Chief UK Economist Paul Dales speaks to David about his major new study on the theory and practice of tackling financial stability risks in a higher rate world.

Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 16th of February and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. David Wilder here, coming up we'll be hearing about financial stability risks, but first Neil Shearing's with me for our regular post -mortem of the week gone by and a look ahead to the big macro market themes for the coming week. Hi Neil, how's it going?

Neil Shearing

Hi David.

David Wilder

Let's talk about recession. It's been in the headlines in the UK and Japan over the past day or so after their GDP data releases. What do we make of all of this? Are the world's major economies all heading for recession? Is this a UK/Japan story? What's going on?

Neil Shearing

Well look, I think the big picture here is that we need a better definition of recession. So what's happened of course is that Japan has recorded two successive quarters of falling GDP in Q3 and Q4. The UK over the past week has reported the same. So both meet the technical definition of being in recession, which is to say two successive quarters of falling output. However, if you look at what's happening in both economies, I think it's a stretch to say that either are in recession. In the case of Japan, we know that the preliminary GDP data are prone to revision and some of the indicators that officials look at when they're actually calling a recession have actually started to pick up. The Tankan, for example, has picked up in recent months. And in the UK, unemployment has been falling and there are still 800,000 vacancies in the economy. I think it's difficult to call that an economy that is in recession.

Conversely, if you look across the channel to the Eurozone, that just about avoided a recession on this technical definition of two successive quarters. But if you look at what's happening in Germany, and we'll have more to say on this in a major piece of research coming over the next week or so, real signs of structural decline in parts of Germany's economy that we think will continue for several quarters to come.

So, the big takeaway from the past week is that economists should stop thinking about recession as being two successive quarters of falling GDP, get a bit behind the numbers. And actually, once you do that, I think you start to get at the nub of some of the issues facing these economies.

David Wilder

Let's stick on that, the nub of these issues. There's been a lot of focus on the UK being in a technical recession, but also on this data showing falling per capita GDP. What is the debate around that data and what does that tell us about the state of the UK economy?

Neil Shearing

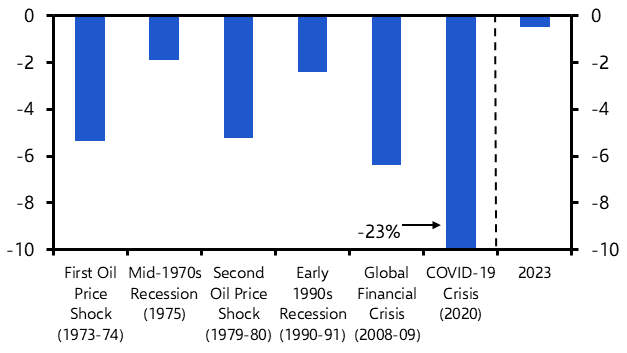

Yes, you're right. The economy being in recession is a gift for headline writers, of course. But actually dig deeper and you're absolutely correct that the big issue is that UK GDP has been flatlining, the economy's been flatlining. And if you look at GDP per capita, so GDP per head, that's now fallen for seven successive quarters. So to the average Brit, things feel pretty grim, even if they've kept their job and the economy's stayed out of recession, living standards have taken a big hit and it feels pretty grim in the real economy. If you look at what's happened, for example, to household consumption over the past couple of quarters, it's fallen in Q3 and Q4. So British households in particular are feeling the squeeze. Now what's behind this fall in GDP per capita, which by the way, the seven successive quarters is the longest decline in recorded history, it's really about the weakness of productivity growth in the UK economy. This is the central challenge.

And this is, I think, the big challenge facing the government. Of course, the government in the UK has pledged to grow the economy. The main message I take from the data over the past week and indeed over the past seven quarters is manifestly failing to do that.

David Wilder

I want to get onto the political economy of the UK and the challenges and choices facing the government and indeed the next government because we're looking at an election in the coming months. But before we get onto that, I want to return to this idea of economic weakness because the big picture, here seems to be US exceptionalism, certainly in terms of what our markets team is focusing on with regard to their work on what's happening with US equities. To what extent is that a macroeconomic story too?

Neil Shearing

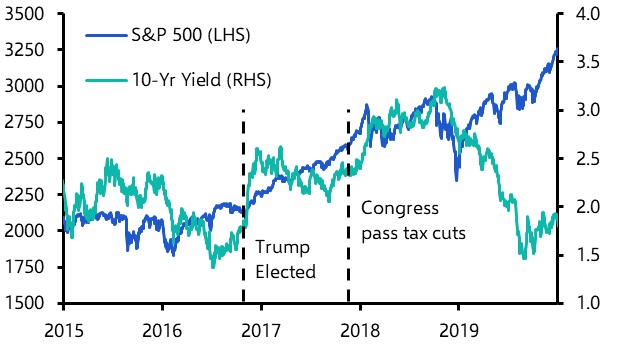

Well, I'd probably separate the two things out. The US equity market, you're right, is incredibly strong. But really that's a story about the so -called Magnificent Seven, the largest tech stocks. It's about AI enthusiasm. And most of the firms that have been the focus of that enthusiasm, are US firms listed in the US and that's what's been driving the US stock market ever higher. We've written extensively about this. Our judgement is that this is an AI bubble, but that the bubble has further to inflate. That doesn't mean to say that the US economy isn't exceptional. It is exceptional. If you look at the GDP performance of the US economy, it is streets ahead of what we've seen in the UK and in the eurozone and for that matter, Japan. Now, why is that? I think part of it is that fiscal policy has been more supportive. I think that if you look at the stimulus that was put in place during the pandemic, it was an order of magnitude larger in the US. The US, of course, is a net energy exporter, so it wasn't hit in any way near the same way as Europe was by the increase in energy prices following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. And on the supply side, because the economy has been run a bit hotter in the US, we've started to see faster productivity growth.

So I would separate out the exceptional performance of the US stock market as really an AI story. The bigger issue, I think, is the fact that the macro economy has been exceptional in its performance over the past couple of years, certainly when we compare against economies in Europe.

David Wilder

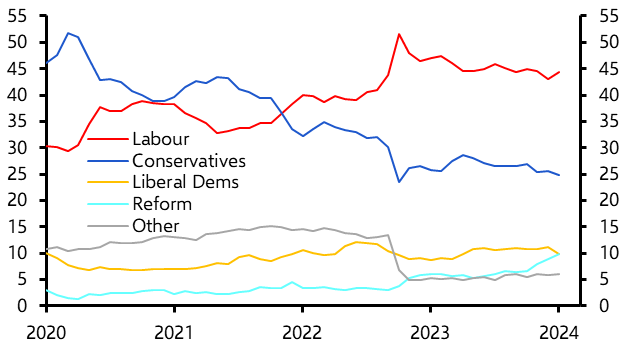

I want to go back to what you were saying earlier about the UK economy, these fundamental challenges. You mentioned productivity. That's obviously in part an under -investment story. We've got elections coming up in the US and the UK in the coming months. Campaigning's basically begun in both countries. We've had analysis out these past couple of days which talks about these tough fiscal choices that the victors in these elections will face, whether it's Biden or Trump or Sunak or Stama. So we'll have much more to say on these elections in the coming weeks or months. But for now, talk a bit about what awaits the next US president and UK prime minister.

Neil Shearing

Well, I think one point to make from the start is that the economy, I think, is still centrally important to elections and it's certainly going to be very tough for incumbent governments to win and retain power if the economy is struggling. But of course, in a world where politics has become more polarised, in a world where culture wars have started to increase, it has a little less bearing. We'll wait and see how that plays out over the course of this year. The one thing we can say is there's a big difference, as I said earlier, between the performance of the US economy and, for example, the UK economy over the past couple of years.

If you gave the UK government the US economy, they would bite your hand off in terms of economic performance. They would absolutely bite your hand off for that kind of performance. So US economy is doing much better than the UK economy. The similarities though, I think, is that across advanced economies, if you look at what's happening in the public finances, there has been a substantial deterioration in fiscal positions across developed markets.

So when you say what awaits the incoming governments, the incoming government in the US, whatever form it will be, I think will inherit an economy that is in reasonable shape. Inflation is going to be lower, but the fiscal position looks a bit troubling, so there's going to have to be some fiscal repair work. In Europe, you've got basically flatlining economies. I think inflation will be lower come election days later this year, but flatlining economies, low productivity growth, and also fiscal repair job to be done. So the commonality across all advanced economies is that fiscal positions have deteriorated and there's some repair work to be done. The question I think for governments is going to be how to sequence that, how to pace that. We learned in 2010 that if you do that against a backdrop of weak private demand, then all you do is squeeze GDP growth. It becomes a self-defeating period of fiscal austerity. So sequencing a fiscal correction so that you don't kill the economy, but at the same time you reassure bond markets so you don't create a bond market meltdown is going to be quite challenging, I think, for governments on both sides of the Atlantic.

David Wilder

That was Neil Shearing on recession, inflation and the reality of fiscal constraints facing the next leaders of the US, the UK and in fact governments worldwide. I'll link to those two notes on the fiscal issues around the US and UK elections on the podcast page. Check out our dedicated US election page, which will be hosting all our key analysis on the vote in the run up to November.

In the coming week there'll be new analysis on that page about what the Trump presidency could mean for financial markets, so watch out for that. And that Germany report that Neil mentioned, that will be out in the coming week as well, and we'll be talking about it on next week's episode. On the UK we're holding a Drop-In, that's one of our short form online briefings, to preview the general election on the 13th of March. I'll put details of that on the page. Read our election preview, attend the Drop-In, and put your questions to Paul Dales and the team.

There's another Drop-In this coming week all about South Africa's budget announcement. The government there is under pressure to increase spending ahead of an election due to be held in the coming months, but public finances are creaking and our EM team will be online shortly after the statement to take your questions and discuss whether Finance Minister Enoch Godawana has held the line. That's on Wednesday at 10am New York, 3am London 5 o'clock JoBurg. If you're a subscriber to CE Advance, you get access to all our drop -ins as part of its total access offering. That also includes all our data and engagement tools for you and your team to get in direct touch with our economists with your specific macro market questions. Now, back to Paul Dales. He's our Chief UK Economist and he's just completed new analysis all about the risks to global financial stability.

In that zero rate world of the before times, doomsayers warned that raising rates would trigger the mother of all systemic crises. That didn't happen. Rates have been jacked up to about 5 % and for the most part all is relatively calm. Does that mean the global economy has dodged a bullet? Hall's analysis talks through the risks of instability based on where we are now, but also explores the risks more generally in a higher rate world.

I caught up with him earlier to ask about the risks we're facing and started by asking whether we have indeed dodged a tightening induced crisis.

Paul Dales

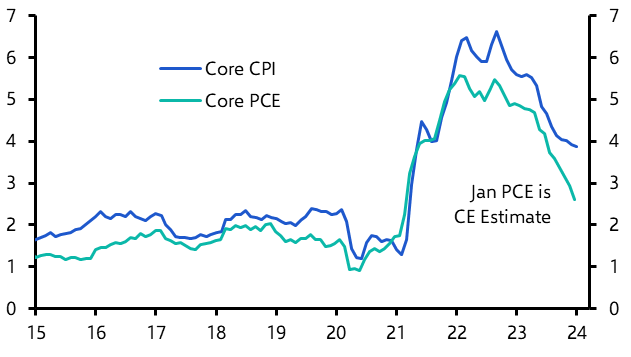

Well, there has certainly been some pockets of short lived instability. Those include the collapse of SVB Bank in the US, the demise of the European investment bank Credit Suisse and the UK's liability driven investment crisis in the pension sector. There hasn't really been any major systemic event that threatens to take down the whole financial system. It's probably too soon to sound the all clear on this, but I suspect with interest rate cuts on the horizon, policymakers are feeling a little bit more relaxed that they haven't exposed some really big financial imbalances. You've just completed this analysis which talks about financial stability risks in a world of higher rates. It follows on from work we did last year on r* on the structural increase in interest rates post pandemic. Now, obviously there was a scramble for yield when rates were at zero pre -pandemic and we saw all manner of asset prices being inflated, didn't we? I mean, when rates looking ahead are now at say three, four or five percent, does that sort of speculative behaviour go away?

Paul Dales

To some extent, yes, I think it does. After all, in a higher interest rate environment, investors won't feel the need to take such big risks in order to secure yield. And I think this is particularly important in those systemically significant areas like housing and credit, which rely very much on debt. But this doesn't necessarily mean there won't be any excessive behavior. It might just show up in different places in different forms.

So for example, we think there are some risks building in the equity market at the moment in relation to the rapid rise in equity prices driven by investor enthusiasm over artificial intelligence. Now this might mean that the next big financial event is something similar to the dot -com crash in the equity markets in the early 2000s rather than the housing crash in the Global Financial Crisis later the same decade. But I suppose of some comfort is that if that were the case, then equity prices aren't as systemically important as the housing market. Let's get into the theory. I'm wary of getting too far into the weeds on this, but it does seem at the heart of your analysis is this concept of a R**. So not r**. What is R** and how does it help us understand the relationship between financial stability and interest rates?

Paul Dales

Well, the concept stems really from the theory of the equilibrium interest rate or R star. And that's the rate of interest that would mean that the economy is growing at its potential growth rate and inflation is in line with the target. So it's the steady state or the ideal situation. R star star is a slightly different concept, but it indicates the change in interest rates or a level of interest rates that would trigger a financial crisis. So this theoretical level exists in all economies. And the concept is that if R star star is a very big number, then policymakers don't need to worry about it because they can raise interest rates to achieve their inflation targets without having to worry about triggering a financial crisis. But if R star star is a small number or relatively low number, there might be a situation where policymakers want to raise interest rates in order to bring inflation down, but don't feel completely comfortable doing that because they're worried they'll trigger a financial crisis.

David Wilder

So it's this concept about how policymakers juggle their dual objectives of achieving their monetary policy inflation targets, but also ensuring financial stability. But it also relates to not just the speed with which interest rates rise, and the financial stability risks around that so much as the level. Is that right? You mentioned, for example, the LDI crisis, which seemed to be as much about how violently bond yields rose when the Truss-Kwarteng budget was being rolled out as to the actual level to which they rose.

Paul Dales

Well, this is one of the problems with any such theoretical concept is that it doesn't always apply in every situation. You can't really distill the economy into one very simple equation. So I think the concept of R** be thought about in a few different ways. One is the change in interest rates required that would trigger a financial crisis. Another is the level of interest rates that would be required. But you're right, that doesn't tackle the speed of the change or the speed of the increases, which was crucially important for the liability-driven investment situation. And it also doesn't tackle at all how long you expect to wait before there is a financial event. It's not necessarily the case that once interest rates move up very quickly, the financial event happens immediately. There's been incidents in the past where it's taken some years for imbalances to cause problems. So it's a useful concept, but it's not always brilliant in practice. We need to think about the practical applications of it.

David Wilder

I'd like to hear a bit more about these choices that face policymakers in a higher rate world. Talk a bit about how central banks calibrate interest rate settings to meet their mandates while making sure that nothing breaks.

Paul Dales

The way most central banks do it is by using what they call the separation principle, where they use their monetary policy tools, mostly interest rates, but also quantitative easing or tightening to achieve their inflation target, and then use macro-prudential tools such as limits on loan to value ratios or counter-cyclical buffers for the banking sector to achieve their financial stability targets. So in an ideal world, there's no sort of conflict. In reality, I think that there are occasions when the separation isn't quite so clear and there are periods when perhaps central bankers don't want to raise interest rates quite as far as they would otherwise because of concerns over financial stability. Or actually it works the other way as well, where there might be periods where central bankers are already worried about existing balances and they want to keep interest rates a little bit higher than otherwise and accepting that inflation will be lower because they want to try and prevent those balances from building up further. So these are the realities that central banks are going to have to always deal with and those realities aren't going to go away even as we move into a higher interest rate era.

David Wilder

Paul Dales there on financial stability risks in a higher rate world. I hope that conversation's given you a flavour of what's in Paul's analysis. He goes into much more detail in the report, including the theory, but also the practical applications. It's really important insight for the coming years and is a great addition to our large and growing body of work on our start and the post pandemic rate environment. I'll link to all of that on the podcast page, as well as all the other analysis and events that we discussed in this episode.

But that's it for this week, we'll be back next week with much, much more on what's happening in the global economy and markets. Until then, goodbye.