The public finances of several key advanced economies are, to put it mildly, in a mess. Recent attention has been on the United States, where the ‘One, Big, Beautiful Act’ has entrenched large federal budget deficits and reinforced concerns that the country is now locked onto a more dangerous fiscal trajectory. But this is not another example of American exceptionalism. Fiscal vulnerabilities are building across advanced economies. France looks particularly worrying, though the UK and Italy are also causes for concern.

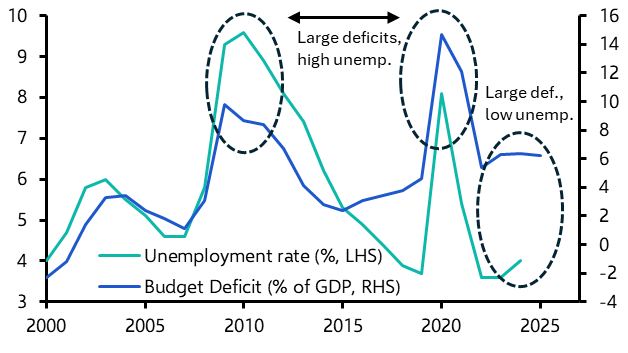

What’s striking is not just the size of these deficits – 6% to 7% of GDP in some cases – but the fact that they’re being run while these economies are operating at or near full employment. (See Chart 1.) That’s a critical distinction from the post-Global Financial Crisis era. Then, government borrowing was a cushion against collapsing private sector demand. As economies recovered, so too did tax revenues, thus helping to repair fiscal positions. In other words, the deficits were cyclical. Not so today. These deficits are structural and so require either tax increases or spending restraint to bring them down.

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

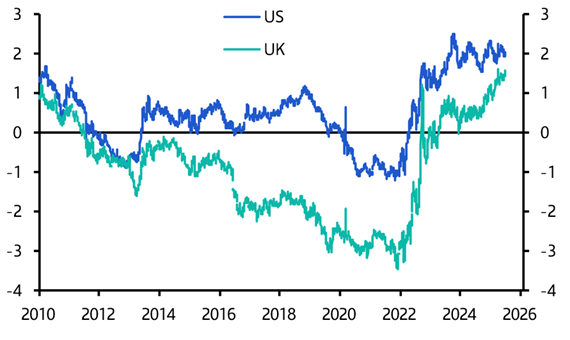

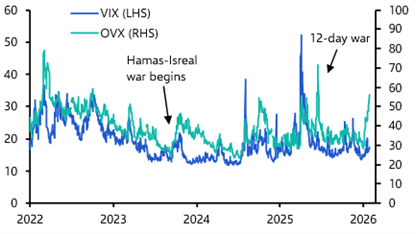

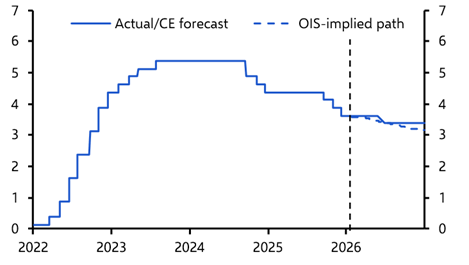

Worse still, this profligacy is occurring in a very different financial climate. Back in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, ultra-loose monetary policies meant that yields on government bonds were negative in real terms. Now, real borrowing costs are in firmly positive territory. (See Chart 2.) The era of “free money” is over. Accordingly, the same deficits that once seemed tolerable – or even desirable – are now a growing fiscal liability.

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

This is the crux of the matter. When governments run large deficits in good times they are storing up trouble. At some point markets will take fright. As the economist Herbert Stein observed about deficits in the late 1980s, “if something cannot go on forever, it will stop”.

Yet there is no neat threshold at which point a crisis hits. No magic debt-to-GDP ratio or fiscal deficit number sets the market alarm bells ringing. Japan, after all, has carried gross public debt above 200% of GDP for more than a decade, sustained in large part by its deep pool of domestic savings. Fiscal sustainability is less about rigid metrics than context and confidence.

And confidence, it turns out, is as much about people as it is about policy.

Events of recent months have underscored this point. The US bond market wobbled in April as concerns over fiscal drift and erratic policy signals, including President Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs announcement, led to a spike in long-term yields. It took intervention from Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and a rapid U-turn on tariffs to calm the waters.

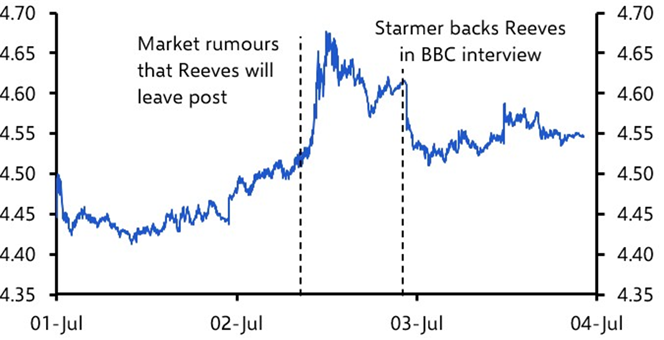

Then in early July, a visibly upset Rachel Reeves in the House of Commons coupled with Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s failure to back her then and there fuelled speculation that the UK Chancellor was on the way out and triggered a sharp sell-off in gilts and sterling. It was only after Number 10 issued a more emphatic statement supporting the Chancellor that the gilt market steadied and yields dropped back. (See Chart 3.)

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

What links theses episodes isn't fiscal policy but personalities. In both the US and UK, investors were reacting not to new revenue or spending data, nor to the wording of any bill, but to who was in charge. They panicked when it appeared that trusted figures in the policy establishment were losing their grip or influence. As a former hedge fund manager, Bessent commands credibility on Wall Street. Reeves, who comes from the fiscally cautious wing of the Labour Party, has staked her political capital on strict fiscal rules. The subsequent recoveries in bond markets weren’t driven by policy shifts, but by relief that credible figures were, or were seen to be, in control.

This is not a new dynamic. Bond markets have long responded sharply to the arrival or departure of key personalities. Mario Monti’s appointment as prime minister in 2011 helped calm Italian bond markets at the height of the eurozone crisis. Conversely, the arrival of Yanis Varoufakis to Greece’s finance ministry in 2015 was instantly, deeply unsettling for holders of Greek government bonds.

The current market mood is a far cry from the panic of the euro-zone debt crisis. But in a world where most advanced economies are running large structural deficits – even at full employment and with higher interest rates – recent moves in the Treasury and gilt markets show that personalities can matter as much as policies, and at times even more. Investors should keep one eye on the fiscal numbers, and the other firmly on who’s in charge. If a crisis does erupt, it’s as likely to come from a change in personnel as policy.

In Europe, the immediate risk is not France’s presidential election in 2027, but an early collapse of the government – potentially leading to an even weaker minority government that gives up on attempts to reduce the deficit. In the UK, the danger is that Reeves is replaced by someone less committed to fiscal discipline. And in the US, fiscal stability may hinge on whether Secretary Bessent continues to retain influence over, and favour with, President Trump.

Fiscal sustainability, then, is increasingly a matter of political sustainability. The markets are watching – not just the numbers, but the names.

In case you missed it

If Donald Trump goes ahead with 30% tariffs on the EU on 1st August, that would result in a hit to German GDP of 1.1% over the next three years, according to our Tariff Impact Model. This improved dashboard lets you simulate country- and product-specific tariff scenarios with greater precision, layering them over baseline rates and exemptions.

How at risk is the post-Liberation Day markets rally from Trump’s latest tariff threats? Our Markets economists are briefing clients in two Drop-Ins this coming Wednesday. Click here to register for sessions in Asian and US hours.

Stablecoins – asset-backed cryptocurrencies that are redeemable at par – may be seen as an opportunity for a certain type of investor, but financial and monetary authorities are wary of their rise. This FAQ explains why as it tackles the key issues for global macro and markets.