We had expected 2022 to be a year in which growth generally disappointed, central banks struggled with sticky inflation and the lingering effects of the pandemic remained the biggest source of uncertainty for macro and market outcomes. And then Russia invaded Ukraine.

Taking a longer term view, the invasion’s start on 24th February may come to be seen as the fundamental moment of change for the post-Cold War world (though there are many candidates). The nearer term impact on economies and markets of Vladimir Putin’s war has been far easier to capture: as my assessment of the year’s major themes shows, it is the singular event that has come to dictate much – but by no means all – of how they performed in 2022, and the war’s continuation will play a big role in how 2023 shapes up as well:

Inflation returns: 2022 will go down as the year in which inflation awoke from its 30-year slumber. Prices were already rising sharply as economies emerged from the pandemic, but Putin’s war supercharged food and energy costs, helping push headline inflation rates to four-decade highs across the US, Europe and most emerging markets. More worryingly, as recovering demand ran into supply constraints, core inflation increased to rates not seen since the 1970s.

The central question for markets in 2023 is how far and how quickly inflation now drops back. We expect headline inflation to slow across the major economies over the next year and suspect that the inflation picture will look much less troubling in 12 months’ time. But the speed at which inflation cools will vary across regions. As we argued in recent notes, price inflation is likely to slow more quickly in the US than it is in Europe.

Central banks fight back: Having spent most of last year talking about the need for restraint, central banks spent most of this year scrambling to raise interest rates. The Fed’s “Flexible Average Inflation Target” (remember that?) was quietly sidelined, only to be replaced by the most aggressive tightening cycle across major economies in four decades. The problem central banks now face is knowing how much is enough. Old models for forecasting inflation have been undermined, causing central bankers in some countries to put more weight on actual inflation when setting policy. The risks of error are high.

We expect that most central banks still have more work to do and anticipate further increases in interest rates in the US, euro-zone and UK in the first half of next year. But interest rates in some EMs (including Brazil, Hungary and Chile) may have peaked, and by mid-2023 we suspect rates in most DMs will have peaked too. More importantly, we think that the Fed may start to cut rates in the final months of the year – although policymakers in Europe are unlikely to follow suit until 2024.

Recession fears mount: The flip side of rapid policy tightening is the growing likelihood that the global economy falls into recession in 2023. Admittedly, recent activity data in both the US and Europe have been more resilient than we had anticipated. But most surveys are now consistent with a sharp slowdown in growth and recessions in Europe. And our proprietary models point to a 90% probability that the US is in recession in six months’ time.

We expect most major economies to fall into recession over the first half of 2023. But crucially, this recession will be more “normal” compared to the extreme downturns experienced during the 2007-08 global financial crisis and the 2020 Covid pandemic. And by the second half of next year, we anticipate that recoveries will begin in most economies. That said, while the US recession is likely to be mild, the euro-zone will suffer a larger downturn due to the huge hit to its terms of trade caused by the Ukraine war.

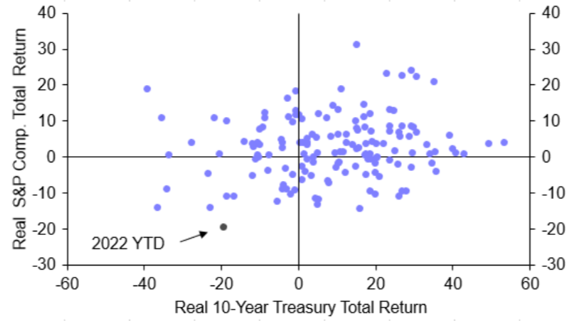

Market turmoil: Geopolitical tension and aggressive monetary tightening conspired to spook markets in 2022, driving up bond yields, snuffing out the rally in “risky” assets and further strengthening the dollar. As a result, the year was an extreme outlier for markets – producing large inflation-adjusted losses for both bonds and equities. (See Chart.) While there have been some extreme moves in the market’s more overvalued pockets, the sharp sell-offs of 2022 have failed (so far) to generate major financial instability issues. In this regard, the UK gilt market’s September-October meltdown was an isolated case of investors reacting to a government which had trashed its credibility.

|

Real Annual Returns (%, 1873 - 2022) |

|

|

|

Sources: Shiller, Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Housing markets go from boom to bust: We see risks of instability more likely to emerge in housing markets, which are cooling rapidly as rates rise and affordability becomes stretched. Housing is the weakest link in this downturn and those economies that saw the biggest run-up in house prices (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the UK) are especially vulnerable.

But EMs prove resilient: Fed tightening and a surging dollar have traditionally been catalysts for emerging market debt blow-ups. But this year was notable for the absence of widespread problems in emerging economies. That doesn’t mean EMs are off the hook; their economic and financial vulnerabilities are larger going into 2023 than they were at this point last year, not least around the sharp increase in local-currency denominated household and corporate debt. We’re not expecting explosive crises in the major EMs like those seen in past decades. But higher debt burdens and higher interest rates will result in weaker GDP growth.

China mis-read: China has had problems different to those suffered elsewhere in the global economy. The outlook has brightened in recent weeks as the government has taken the first steps towards relinquishing its policy of zero-COVID. But while local markets have rallied, shifting to a policy of “living with COVID” will be more difficult than many now seem to assume. The experience of other countries suggests that China will experience renewed waves of infections as it reopens, which will bring more near-term disruption to the economy. And even if everything goes right on the COVID front, the economy still faces the considerable headwinds of problems in the property sector in decline and fading export demand. China’s economy should end 2023 in a much better position than it is in now – but the path between now and then will be a bumpy one.

Global fracturing: We think some of the Ukraine war’s long-term influence is apparent – it’s the latest in a series of shocks to hit the global economy following the US-China trade war and the pandemic, and the consequences of these will reverberate through the coming decades. Our annual Spotlight project argued that the post-Cold War phase of globalization won’t simply go into reverse. Instead, we showed how the world economy is coalescing around US- and China-aligned blocs of countries and how this will reorder existing flows of everything from trade to finance to technology. Despite efforts by the US and China to get back to business toward year-end, Spotlight’s core message is unchanged: geopolitics is back as a driver of policy choices and economic outcomes.

What you may have missed:

- We’ll be wrapping up a packed week of central bank decisions in a special Drop-In on Thursday at 15:00 GMT. Register here for the 20-minute online briefing.

- The outcome of the Fed’s December meeting could be overshadowed by the official US CPI report the day before. Chief US Economist Paul Ashworth explains why.

- The latest episode of our weekly podcast includes discussion of the challenges for central bankers as tightening cycles mature, as well as Lula’s chances of curbing Amazon deforestation when he returns to the Brazilian presidency in January.