Tariff-driven price pressures are finally starting to show up in the US economy. June inflation data offered early evidence that President Trump's tariffs are feeding through supply chains and those pressures are only likely to build – we think core inflation will reach 3.3% y/y by end-2025, with core goods inflation hitting 4.4%. Those increases will no doubt dominate headlines over the coming months and higher inflation and a relatively resilient economy are likely to keep the Federal Reserve from cutting rates until next year.

But shouldn’t mistake noise for signal. Tariffs may lead to a one-off increase in prices at the border, but the real action in global goods inflation – or, more precisely, disinflation – is unfolding not in America, but in China, where industrial overcapacity and collapsing prices tell a far more consequential story.

Still made in China

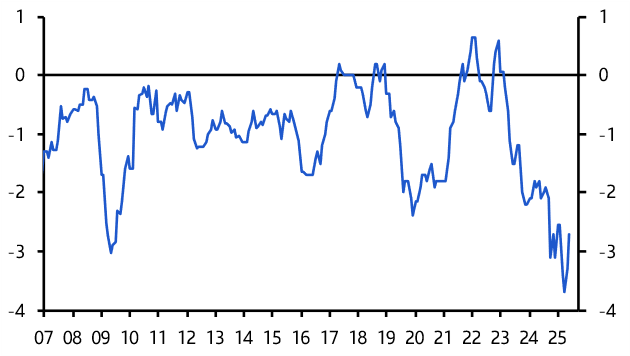

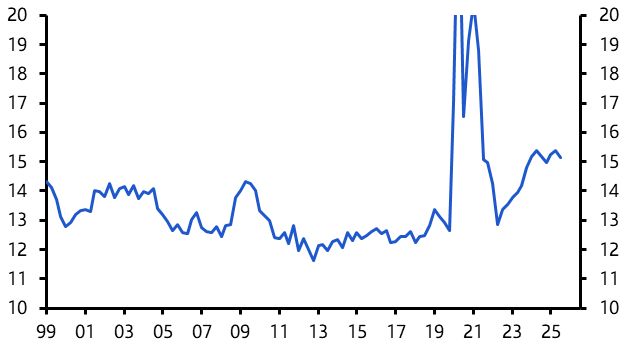

The latest data are stark. Factory gate prices for consumer durables in China are now falling at their fastest pace since the depths of the global financial crisis in 2009. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: China PPI – Consumer Durables (% y/y) |

|

|

|

Source: LSEG, Capital Economics |

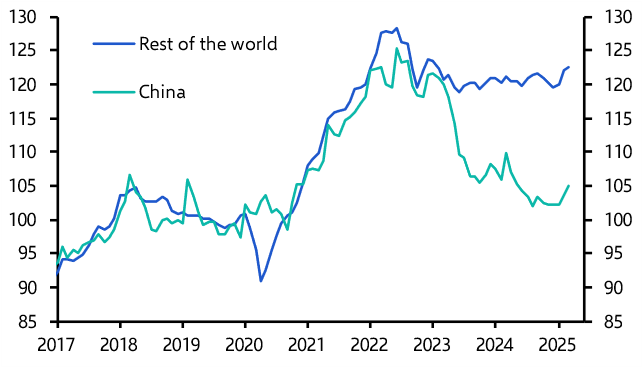

And while export prices from most countries have flatlined over the past couple of years following their pandemic-era surge, those from China have slumped by more than 20%. (See Chart 2.) All other things being equal, this will have reduced goods prices in most advanced economies by around 0.4%-pts. China is now a key source of global disinflation.

|

Chart 2: Goods Export Prices (2019 = 100) |

|

|

|

Source: LSEG, Capital Economics |

This is, of course, nothing new. Veteran watchers of the global economy will remember that China played a central role in the low-inflation era of the 2000s. Back then, it was the integration of low-cost Chinese manufacturers into global supply chains that brought prices down across the Western world. But what we are witnessing today is subtly different.

A brutal price war

This latest wave of falling prices out of China is not about productivity gains made possible by globalisation. Vicious price wars are raging across Chinese industry as firms fight to maintain market share and offload excess capacity. The leadership in Beijing has had enough. President Xi Jinping has called for an end to “disorderly competition” while Party publications routinely condemn “involution-style” competition – which refers to margin-destroying price wars driven by overcapacity. Regulators across industry are hauling in firms to try to stop the bloodshed.

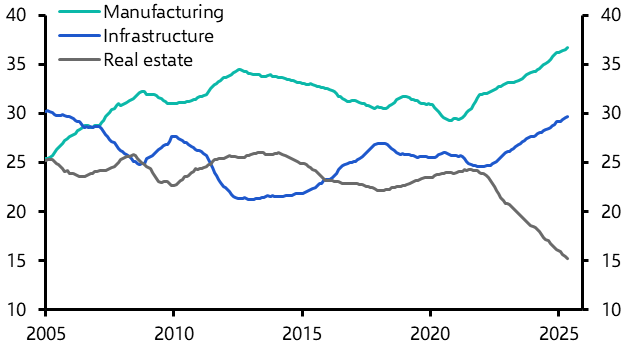

But state decrees cannot resolve an issue that is structural in nature. China’s economic model is fundamentally unbalanced. For decades, China’s development has been built on sky-high rates of savings and investment. Investment still accounts for around 40% of GDP, a level unheard of in any other major economy. And while property once soaked up a quarter of that investment, China’s real estate bust has forced a shift. As a result, manufacturing is taking an even bigger share of investment, absorbing nearly 40% of the total. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: China Fixed Investment by Sector)% of total, 12m ave.) |

|

|

|

Source: LSEG, Capital Economics |

The structural weakness of domestic consumption (the corollary of high savings) has seen a flood of goods leave Chinese factories for global markets at cut-throat prices. The effect on profit margins has been brutal. One estimate suggests as many as 30% of China’s manufacturers are now losing money, staggering on and sustained by local government support and soft-loans from state banks.

China’s leadership is in an unenviable position. Understandably, it wants to rein in price wars and prevent the spread of zombie companies whose survival depends on state support. But it also wants to promote emerging industries and boost self reliance. Throw in the pressures to maintain employment and deliver growth, and these efforts to curb excess capacity become riddled with contradiction.

The truth is that China needs to rebalance its economy not through regulation or a redirection of investment, but by engineering a structural shift toward higher consumption and lower savings. This is no small task, not least because it will require a profound cultural and institutional shift.

Mapping the consequences

The implications of all this extend far beyond pricing dynamics. In the short term, China’s industrial glut is acting as a powerful disinflationary force across the global economy – something that global central banks, still licking their wounds from the recent inflation surge, may quietly welcome.

But the longer term consequences are more troubling. For China, a model built on relentless investment and weak consumption has now reached its logical conclusion: chronic overcapacity, wafer-thin margins and ever-diminishing returns. Unless Beijing can engineer a decisive rebalancing toward household consumption, the economy faces a future of substantially lower growth. It is plausible that GDP growth could sink to as low as 2% a year by the end of this decade.

Meanwhile, competition from China is a challenge for the rest of the world. The torrent of cut-price exports spilling into global markets is triggering alarm – not just in Washington, Brussels, Tokyo, but in emerging markets too. Its bid to secure global dominance in strategic industries – from electric vehicles to green technology – puts China on a collision course with major advanced economies. But Chinese firms are continuing to grow market share in labour-intensive, lower-end industries too, which is challenging development norms and fuelling trade tensions across emerging markets.

Tariffs may be a crude response, but they are symptomatic of a broader shift: a world that is increasingly unwilling to absorb the logical consequence of China’s sky-high saving and investment rates. What was once an engine of global growth is fast becoming a source of geopolitical friction.

In the end, this is not just a story about inflation or trade. It is about a fundamental transformation in the global economic order – one in which China’s growth model is no longer perceived to deliver unalloyed benefits, and the rest of the world is increasingly unwilling to accommodate it.

In case you missed it

- The LDP’s poor showing in Japan’s Upper House elections may increase pressure for fiscal stimulus, but we don’t think the country’s public finances are as precarious as widely assumed. While we expect the 10-year JGB yield to rise to 2% by end-2026, we see that move as driven more by shifts in monetary policy than by fiscal concerns.

- Our US team explored the policy and financial market implications of what would happen if Donald Trump did fire Jerome Powell. Deputy Chief North America Economist Stephen Brown also talked through the ramifications on this week’s podcast.

- Ongoing deliberations at the South African Reserve Bank could reshape its inflation-targeting framework and set the stage for a potential 200bp rally in local currency government bonds. Our EM team will unpack the implications of this possible repricing in a Drop-In briefing this Thursday. Click here to join the discussion.