It wasn’t so long ago that markets would barely take note of a major summit or meeting between political leaders. These days, bilateral get-togethers are followed by a scouring of accompanying communiques for signs of shifting geo-political allegiances and emerging areas of tension. The visit to China of US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen was no exception.

The optimistic take is that the visit provided further evidence that both sides are trying to improve relations following an escalation of tensions between the two countries. Yellen noted that the bilateral relationship was “on a stronger footing” than this time last year. Her trip followed a meeting between Xi Jinping and Joe Biden in San Francisco in November which was widely seen as an opportunity to stabilise relations, and a call between the two presidents earlier this month. Optimists argue that relations have come a long way from the recent low point early last year when the US shot down what was widely believed to be a Chinese spy balloon over North American airspace.

The more sceptical view of recent developments in the bilateral relationship is that getting the two sides talking again is a low bar to clear. The underlying causes of tension between the US and China have not gone away. China has emerged as a geopolitical rival to the US and a threat to US interests. Yellen’s warning in Beijing that any moves to bolster Russia’s military capacity could expose Chinese banks to US sanctions was a stark reminder of this. It was also a theme of the call between Biden and Xi. According to the White House readout, Biden told Xi that US curbs on technology exports to China were intended to prevent them “from being used to undermine our national security”. Both sides have been making efforts to thaw relations, but the key fault lines of US-China fracturing remain.

Indeed, Yellen’s visit crystallised growing concerns within Washington and among its allies about the massive expansion of Chinese industrial capacity since the start of the pandemic, and the corresponding fear that it will cause a glut of goods to be “dumped” on markets in the West.

Chinese factories in overdrive

Chinese industrial output has increased by about 25% since the end of 2019. This partly reflects investment in capacity to meet the surge in global demand for consumer goods during the pandemic, but investment has continued to flow into the industrial base, even though global demand has largely normalised. The bigger picture is that policymakers in Beijing are still wedded to an investment-led growth model. And with the property sector in crisis they have sought to channel more resources to industry instead, particularly to areas such as high-end electronics, batteries and electric vehicles that Beijing sees as strategically important.

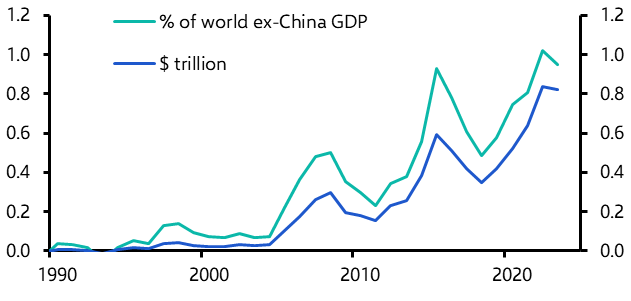

This increase in supply is now being shipped overseas. China’s goods trade surplus has exceeded $800bn in each of the past two years. That puts it close to the equivalent of 1% of the rest of the world’s GDP, twice as large in these terms as it was on the eve of the Global Financial Crisis. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: China’s goods trade surplus |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

In one sense, a substantial expansion of global industrial capacity is a strange thing to worry about for policymakers burnt by the largest inflation shock for forty years. As we have noted before, China is now exporting disinflation to global goods markets – the price of the typical export from China is more than 10% lower now than it was a year ago. This is helping those central banks, including the Federal Reserve, that are still facing uncomfortably high rates of headline inflation.

Trying to stop the tide

However, governments have reasonable concerns that Chinese firms that receive extensive state support are not operating on a level playing field. Yellen noted that previous episodes of Chinese overcapacity had “decimated industries across the world and in the United States”. Protecting and rebuilding these industries has become one of the few priorities that unites politicians from both sides of the aisle in the US, even if there is little evidence of this happening in practice. Governments in Europe are also pushing back against state-subsidised Chinese production. The European Commission followed up last October’s anti-subsidy probe into electric vehicle imports from China with separate investigations starting this month into imports of solar panels and wind turbines.

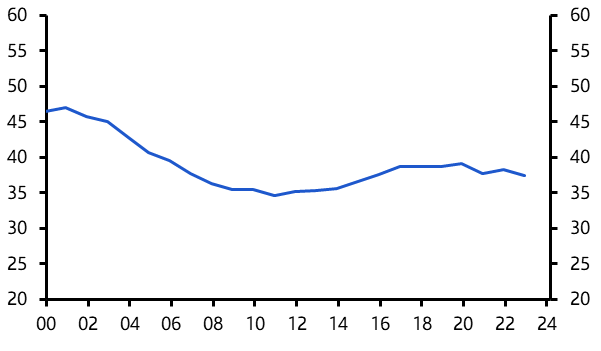

However, it is difficult to see how US and European concerns about Chinese overcapacity will be resolved. China has added more than 5% to global manufacturing output since 2019. At the same time, demand from within China for these products remains relatively low. Consumer spending still accounts for less than 40% of China’s GDP, compared to 70% in the US. (See Chart 2.) As a result, Chinese firms have no alternative but to sell additional output overseas. And given China’s size, the only economies large enough to absorb the additional capacity are the US and European Union.

Pushback on Yellen’s complaints about Chinese dumping from several officials, including Vice-Finance Minister Liao Min, underscored the diplomatic challenge facing the US and its allies in getting Beijing to budge.

|

Chart 2: China Household Consumption as % GDP |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

No signs of a policy shift

The long-term solution is for China to develop sources of domestic demand. The problem from a macroeconomic perspective – if not from a political one – is not so much that China’s exports are too high relative to its economy or the global economy but that they are so much higher than its imports. Redressing this will require China’s saving rate to fall and the share of GDP accounted for by household consumption to rise. (Incidentally, the exact opposite shift is needed in advanced economies with low levels of investment, including the UK. Politicians will happily talk about the need to raise investment but few acknowledge that funding this will require savings to rise and consumer spending to fall as a share of GDP.)

However, despite its evident flaws, China’s leadership is ideologically wedded to a high savings-high investment growth model. The IMF and others have been pushing China to reduce savings and stimulate consumer spending for several decades only to see the share of GDP accounted for by household consumption actually fall. (Again, see Chart 2.) There is no reason to believe that a change is now imminent.

Accordingly, despite pressure from the US and Europe, China is likely to remain highly reliant on external demand for several years to come. This will have both political and financial consequences. The political consequences are obvious: concern in Western capitals about Chinese overcapacity and under-consumption will intensify, and will become an increasing focus of policy. If Donald Trump prevails in this year’s election, it will be used as justification for the imposition of large tariffs on imports from China.

The financial consequences have received less attention. The consequence of China’s surplus is that large amounts of foreign earnings are generated that must be invested somewhere. And given China’s size, the US and Europe are the only markets capable of absorbing such inflows. The debate so far has focussed on China’s trade surplus rather than the capital flows that are its necessary counterpart. If the US and its allies start to target these flows with selective investment controls then the dislocation in financial markets could be substantial.

We discussed the political economy surrounding the increase in Chinese overcapacity in the latest episode of The Weekly Briefing. Listen to it here or subscribe via Spotify or Apple.

In case you missed it:

- Our instant reaction to the macro consequences of Iran’s drone attack.

- Paul Dales unpacks Ben Bernanke’s review of forecasting and communications by the Bank of England.

- William Jackson assesses sovereign debt risks in emerging markets.