There’s some dispute as to whether UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan ever actually said “events, dear boy, events” when asked what can blow governments off course. Whatever its provenance, the quote does capture how economic forecasts can be blown off course too – with recent developments in China a case in point.

We had anticipated that China’s path out of zero-COVID would be a bumpy one, with both supply and demand hit hard in the first quarter of this year before a recovery took place in the second.

But, in what is shaping up to be a key macroeconomic event for 2023, the high frequency data that we track suggest that a significant rebound is already underway.

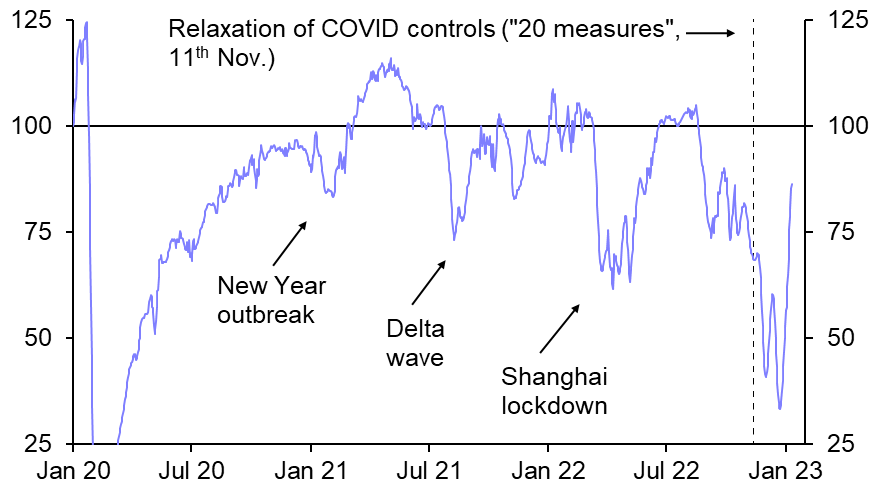

For example, subway traffic in major cities is rapidly returning to normal. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Subway Ridership in 23 Major Cities in China (% of 2019 level, 7 day avg.) |

|

|

| Sources: Baidu, WIND, Capital Economics |

At the same time, the policy sands are shifting. In particular, the leadership’s decision to step back from its “three red lines” policy suggests that the turn in the property sector may now come sooner than we had anticipated.

You can read our full analysis here, but the bottom line is that we have pulled forward the timing of China’s post-COVID rebound and now anticipate a significant recovery in output over the coming months. Consistent with this, we have pushed up our forecast for economic growth this year on our China Activity Proxy measure from 2% to 5.5%, albeit at the expense of growth in 2024 (which we’ve pulled down from 8% to 5%).

This could have implications for the global inflation outlook this year – but not for the reason that many think.

It’s not the supply side

There is a widespread perception that supply problems in China have made a significant contribution to the inflationary surge in the West. As a result, any change in China’s supply side as a result of the shift to living with COVID – either because new waves of the virus lead to increased worker absences or the end of lockdowns improves the supply situation – will, according to this view, have significant implications for inflation in the US and Europe.

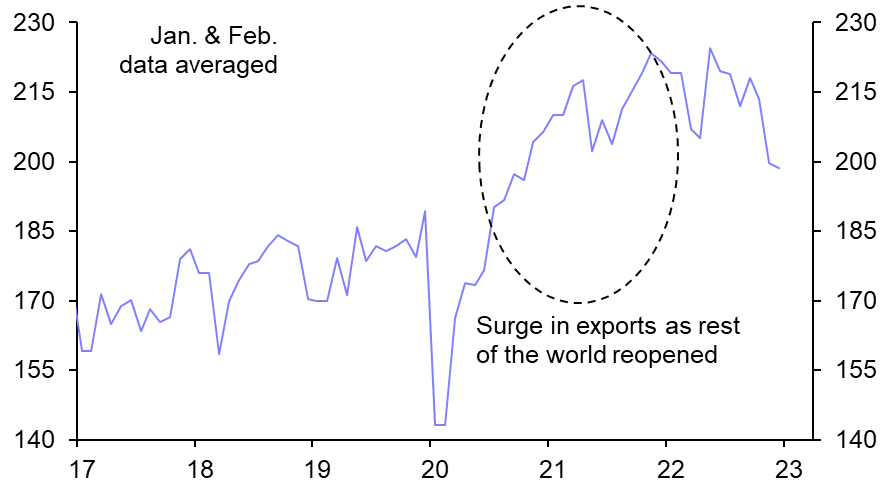

But this is a misread of what caused the initial surge in inflation in advanced economies following the pandemic. The jump in goods prices in the early stages of the inflation shock was caused primarily by a surge in demand, driven by a combination of stimulus and a shift in spending patterns, rather than a diminution of goods supply from China. Indeed, supply from China increased substantially in 2020-21. This can be seen most clearly in the jump in China’s exports during this period. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: China Exports ($bn, Seas. adj., 2010 prices) |

|

|

| Sources: WIND, Capital Economics |

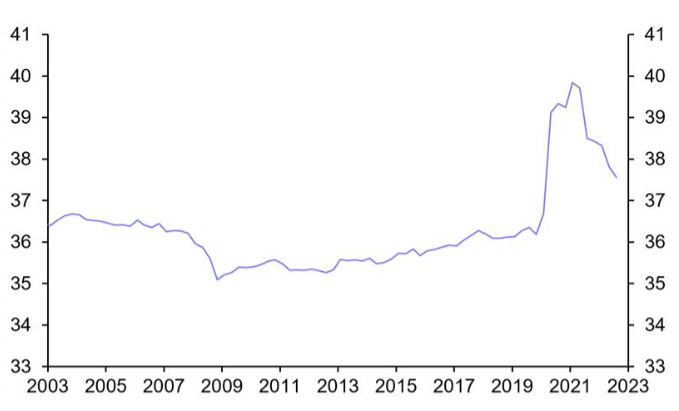

Recurring outbreaks of the virus are likely as China shifts to living with COVID, and responses to the PMI surveys in December suggest that manufacturers have experienced an increase in worker absences. But inventory has been rebuilt along global supply chains and global demand for goods is now weakening – both because policy tightening is dampening aggregate demand, but also because spending patterns in advanced economies have shifted back to services and away from goods. (See Chart 3.) Accordingly, we don’t anticipate a renewed inflationary surge in the rest of the world driven by shifts in China’s supply-side.

|

Chart 3: Goods Share of Total Real Private Consumption (G7 Economies, %) |

|

|

| Sources: Refinitiv |

Look to the demand side

If the faster-than-anticipated rebound in China is to generate higher inflation elsewhere, it’s more likely to come through what’s happening on the demand side. China’s consumption of energy fell last year as lockdowns disrupted travel and sapped demand. The economic rebound this year will lead to a sharp increase in China’s demand for energy. This in turn will put upward pressure on global energy prices.

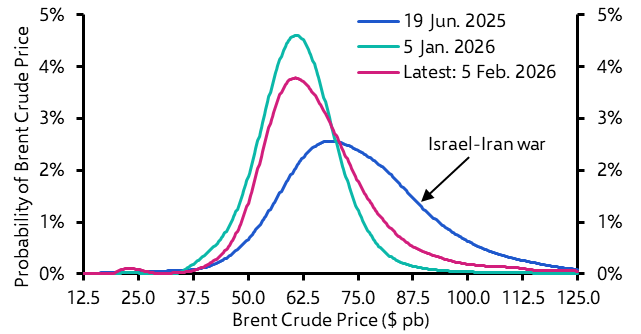

However, as our Chief Commodities Economist, Caroline Bain, set out in a series of client “Drop-Ins” last week, competing forces are at play. On the one hand, demand from China is set to rise. But on the other, demand from the US and Europe will be constrained by recessions in both regions. Putting those two things together, we anticipate that total demand for oil will rise by 1.3m bpd this year. Factoring in continued supply constraints, we forecast that oil prices will struggle to make gains in the first few months of the year, before embarking on a more sustained rally in the second half. We have raised our end-2023 forecast for Brent crude from $85pb to $95pb.

It’s complicated

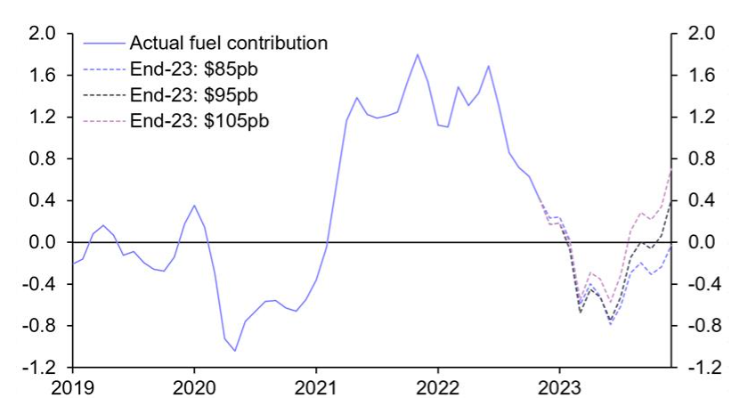

Given the uncertainties around the outlook, it makes more sense to think in terms of scenarios for oil prices and then work through what this might mean for inflation in advanced economies. The main channel that oil prices directly affect inflation is via fuel costs. Chart 4 shows how the contribution of changes in fuel prices to headline inflation in developed markets changes under three assumptions: a low oil scenario ($85pb end-23), a central scenario ($95pb end-23), and a high oil price scenario ($105pb end-23).

|

Chart 4: Percentage-Point Contribution of Fuel Inflation to Average Headline Rate in Major Advanced Economies |

|

|

| Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

In our new central scenario, higher fuel inflation adds about 0.4%-pts to headline inflation in developed markets (DMs) compared to our old forecast (in which oil prices rose to only $85pb). This means that average inflation in DMs will be around 2.6% by end-2023, compared to our previous forecast of 2.2%. That’s significant, but not sufficient to alter the broad picture of disinflation this year (DM inflation is currently running at over 7.5%).

In Europe, we also need to consider the effect that China’s recovery will have on natural gas prices. Mild winter weather helped drive a collapse of European wholesale gas prices over the past month, but LNG shipments have also been easier to secure because of subdued Chinese demand. A faster-than-expected Chinese rebound now means its LNG imports are likely to rebound strongly this year, forcing Europe to compete for gas supplies. This will push up the price of LNG and, in turn, raise the price of Europe’s TTF gas benchmark back towards €100 per MWh, from around €65 currently.

The inflation outlook in Europe is muddied further by the effects of government support packages, which will mean that the impact on household energy bills will vary from country to country. In the case of the UK, for example, our new forecasts are consistent with a rise in household gas and electricity prices in April, when the government’s energy price guarantee is reviewed, followed by a fall in prices at the following tariff review in October.

This all means that China’s reopening could substantially change the DM inflation outlook if it means oil prices are pushed above $100pb for a sustained period and European gas prices behave similarly. But it’s a much more complicated and nuanced story than the prevailing concern that reopening simply means more supply side inflation risk.

What you may have missed:

- In his preview of the Bank of Japan’s meeting this week, Marcel Thieliant explains why and when its Yield Curve Control policy may be scrapped (register here for our post-BOJ online briefing on Wednesday).

- Chief Markets Economist John Higgins previews the Q4 US earnings season to make our case for the S&P 500 revisiting recent lows before a recovery takes hold.

- Vicky Redwood shows why a Labour Party victory in the next general election probably wouldn’t mean much for the UK’s economic outlook.