The past year has underlined just how influential a handful of macro and market forces have become, from the AI investment boom to persistent US-China tensions to the build up of fiscal risks. Those themes will continue to define the outlook for 2026. But not everything carries over. With several narratives that loomed large in 2025 already fading, this lookahead sets out the themes that will matter in 2026 as the global economy heads into another demanding period.

1. The economic benefits of AI will continue to build – and the market bubble will continue to inflate

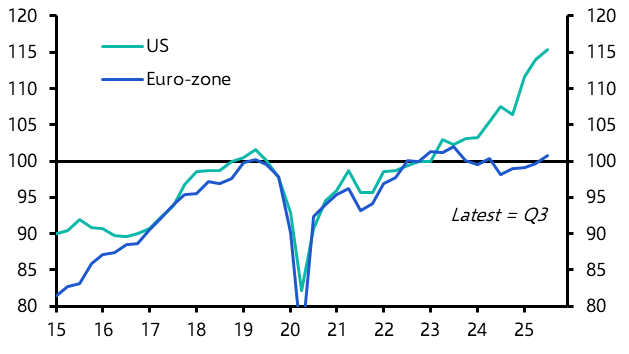

2026 will bring further evidence of the transformative potential of AI, but the economic gains will be unevenly distributed. The technology’s boost to growth next year will be centred on the US and will come mainly from the surge in capital spending needed to build AI infrastructure. Productivity in the US is starting to show signs of improvement, but the near-term lift to growth will depend far more on investment than on a broad, economy-wide productivity jump. AI is already lifting the US economy: by our estimates, it added around 0.5%-pts to GDP growth in the first half of this year. We expect this to continue in 2026, which underpins our above-consensus forecast for the US economy to grow by 2.5% next year.

Elsewhere, however, the picture is less encouraging. AI adoption and associated investments have been slower to take hold outside the US, and there is little sign of this gap closing soon. This is one reason why we expect Europe to continue to underperform. Our GDP forecasts for both the UK and the euro-zone sit below consensus, at 1.2% and 1.0% respectively.

Optimism around AI has been a key reason why 2025 has been another stellar year for stock markets. There is no question that equity valuations are high, especially in the US. But they are not yet as stretched as they were during the last tech-driven equities bubble in the late 1990s and earnings growth should remain solid. As such, we think equities can keep rallying for a while yet: we forecast the S&P 500 to rise to 8,000 by the end of 2026.

2. China will remain stuck in low growth and deflation

While Europe has lagged the US in the development and adoption of AI, 2025 has been a year in which China has closed the gap with America in key areas of AI technology. Yet even as China challenges the US at the technological frontier, its broader economy continues to be held back by deep-seated structural problems. At the core is a growth model that continues to prioritise supply over demand, resulting in chronic excess capacity and persistently weak consumer spending. Policymakers are pledging to address the problem, but the imbalance will remain a defining feature of China’s economy in 2026.

The anti-involution campaign so far appears short of practical steps to reduce capacity. One measure of a lack of commitment is that the authorities do not appear to be considering the offsetting stimulus that would be needed if large-scale factory shutdowns and job losses were being planned. And while fiscal policy will remain supportive next year, this will not deliver a substantial lift to domestic demand. The next Five-Year Plan, which is due to be published in March, is likely to include a target for increasing the share of GDP accounted for by household consumption, but a major policy pivot does not appear to be on the cards: early signs are that the Plan’s overriding priorities will be to sustain the push to lift China’s industrial self-sufficiency and to compete in cutting-edge technology.

The upshot is that economic growth is likely to remain weaker than most anticipate. Our China Activity Proxy suggests the economy is currently growing by around 3% y/y – we expect a similar pace of expansion in 2026. At the same time, the imbalance between supply and demand is likely to cause China’s trade surplus to expand rather than narrow, and will continue to generate significant deflationary pressure. This combination of weak growth and persistent deflation will keep downward pressure on government bond yields. China’s 10-year government bond yield fell below Japan’s for the first time this year, and we expect the gap to widen in 2026.

3. The trade war isn’t over

The deal struck between Presidents Xi and Trump at the end of October – and the series of agreements reached between the US and other trading partners in the second half of this year – has not brought the trade war to an end. Instead, 2026 will be a year in which global trade flows adjust to the tariffs imposed by the US, and in which US-China economic fracturing continues to evolve in unpredictable ways.

While the Xi-Trump accord has removed the immediate risk of further tariff escalation, it has done little to resolve the underlying tensions in the US-China relationship. Crucially, the one-year sunset clause creates the possibility of a renewed flashpoint late in 2026. More broadly, although it’s possible the Supreme Court could strike down parts of the Trump administration’s tariff regime, the growing dependence on tariff revenue suggests the authorities will find ways to keep barriers in place. The restrictions on global trade that were put in place in 2025 will not be dismantled next year.

At the same time, US-China fracturing will deepen. Supply chains for critical goods are likely to continue shifting away from China, while the renegotiation of the US-Mexico-Canada trade agreement (USMCA) may give Washington scope to tighten rules of origin, making it harder for Chinese firms to circumvent US tariffs by routing exports through Mexico. Investment and technology flows will also come under greater scrutiny and may face additional restrictions.

In short, don’t expect a repeat of the fireworks that accompanied “Liberation Day,” but the political forces reshaping the global economy will continue to push the US and China further apart – and will direct patterns of trade, capital and technology flows throughout 2026.

4. Central banks will continue to ease – but Trump won’t get the major cuts he wants

2026 will be a year in which most central banks will continue to loosen monetary policy, but the pace of easing will vary widely and in several cases our forecasts diverge meaningfully from expectations currently priced into markets.

In the US, a combination of a resilient economy and an inflation rate that we expect to hover around 3% on the Fed’s preferred core PCE measure suggest that rate cuts will come more slowly than investors anticipate. If the Fed follows through with another cut this month, we think there may be only one further reduction in 2026. That would leave the fed funds rate in a 3.25-3.50% range, compared with market expectations of a fall below 3% next year. This could bring the Fed into conflict with President Trump, who has been vocal in calling for lower borrowing costs. Our base case is that a change in Fed leadership in May will not fundamentally threaten the institution’s independence or trigger a major shift in policy, but it remains a clear source of risk.

Elsewhere, however, we expect policy easing to go slightly further than markets currently anticipate. In the euro-zone, a combination of weak growth and soft inflation should allow the ECB to cut its deposit rate to about 1.5% next year, compared to market expectations of nearer 2%. And in the UK, we expect inflation to fall faster than both the Bank of England and markets anticipate. Coupled with planned fiscal tightening, this should push the Bank to lower interest rates to 3% by year-end – below the level of 3.5% that is currently priced into markets.

Meanwhile, in the emerging world, the high starting point for real interest rates in Brazil means that the Central Bank of Brazil will have more room to ease as inflation retreats. We expect the Selic rate to fall to 11.25% by the end of 2026, which is more than markets are currently expecting.

All of that leaves Japan as an outlier among major economies. While Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has previously advocated for looser monetary policy, a combination of a tight labour market and additional fiscal support means the Bank of Japan is likely to raise rates again next year. We expect the policy rate to reach 1.25%.

If we are right on all of this, then 2026 should prove to be a better year for the dollar against the euro and sterling, but the yen may strengthen a touch against the greenback.

5. Fiscal risks will continue to stalk markets

The fiscal strains that rattled investors at various points this year will continue to stalk markets in 2026. It is now widely accepted that the public finances of several major advanced economies are on an unsustainable path. France, the US and, to a lesser extent, the UK are all running sizeable budget deficits against the backdrop of already-elevated debt burdens. Italy’s budget position is somewhat stronger, but its debt load is high and the economy’s underlying growth rate remains low. Across all of these countries, the shift from an era of ultra-low – indeed, negative – interest rates to one in which real rates are now positive has pushed up the cost of servicing government debt.

The key question is: how much public debt is too much? In practice, there is no single threshold beyond which a fiscal crisis becomes inevitable. Instead, strains tend to emerge when an economic or political shock prompts investors to reassess a country’s fiscal prospects. Economic shocks can never be ruled out, but our sense is that politics will be the more likely catalyst for fiscal concerns in 2026. Signs that governments are losing their commitment to fiscal prudence, pivoting toward looser fiscal policy, or sidelining individuals who are well-regarded in markets could all unsettle investors. Potential triggers include growing concerns about the outcome of France’s 2027 presidential election, a change in government in the UK, or any sense that respected figures like Scott Bessent are falling out of favour within the Trump administration.

Ultimately, we suspect that a combination of central bank rate cuts and a subtle increase in financial repression will keep government bond markets broadly anchored. But short, sharp sell-offs triggered by fiscal worries – similar to those seen in France, the UK and the US this year – are likely to be repeated at points in 2026.

Although we expect these to be the dominant themes of 2026, a range of secondary forces will also shape outcomes across developed and emerging economies and across sectors and markets. We will be discussing both at our World in 2026 event in London this Tuesday, and in similar events in the US and Singapore in December and into the new year. For those unable to attend in person, we will hold virtual briefings next week and will publish a podcast shortly after – keep an eye out for both in your emails.

Neil Shearing, Group Chief Economist