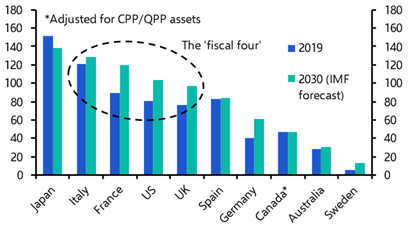

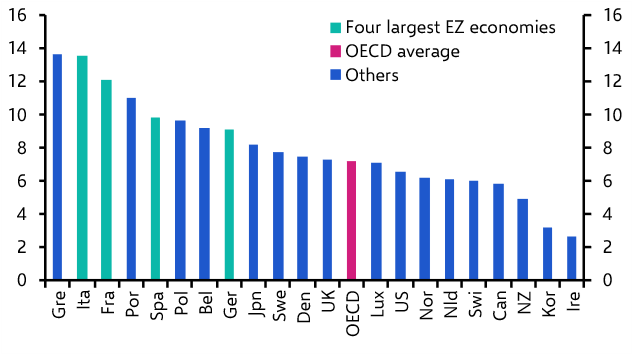

It is now widely acknowledged that the public finances of several advanced economies are on perilous ground. We have identified Italy, France, the United States, and the United Kingdom – the so-called “fiscal four” – as countries where the public finances look distinctly worrying. (See Chart 1.) The question we are asked most often is a simple one: when will something snap? The honest answer is that no one knows.

|

Chart 1: General Government Net Debt (% of GDP) Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

There’s no magic number

At the outset, it’s important to stress that there is no magic threshold for public debt or deficits beyond which crises automatically erupt. In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff made the controversial assertion that economies ran into trouble when government debt ratios exceeded 90% of GDP. But countries have sailed past that figure without experiencing fiscal crises. Japan’s government has sustained a net debt to GDP ratio of more than 150% for decades without sparking a meltdown. In contrast, some emerging economies have experienced fiscal crises with government debt at much lower levels. Around half of sovereign debt defaults by EM governments since 1980 have occurred when public debt has been below 50% of GDP. Eight EM governments have defaulted with public debt ratios below 30% of GDP.

In practice, what constitutes fiscal sustainability is dependent on a wide range of factors – from growth prospects and the inflation outlook to domestic savings rates, the currency of issuance and the credibility of the issuing government. The last two matter most. A sovereign that borrows in its own currency has far more scope to postpone a reckoning, not least through “financial repression” – a tool we will examine in more detail in a forthcoming piece.

The fiscal credibility of governments is also critically important in maintaining investor confidence. Crises arise not from any particular level of debt per se, but from an event that causes investors to change their collective minds about a country’s fiscal prospects. The triggers fall into two broad categories: those that are economic and those that are political. (Table 1 in this Focus contains a useful summary of previous advanced economy fiscal crises and their causes.)

Economic triggers can take various forms. Banking crises are common causes because they can saddle governments with enormous liabilities that can morph into fiscal problems. Another is external shocks that slash economic growth and fiscal revenues by extension. While exogenous shocks can never be ruled out – few foresaw Covid – any fiscal problems in the years ahead are more likely to be triggered by politics.

Is the UK really a fiscal sinner?

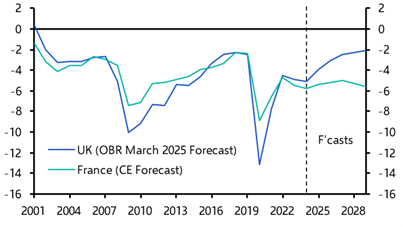

An early test for the UK will come next month in the Chancellor’s Budget. I suspect that Rachel Reeves will be able to cobble together a mixture of tax rises, spending restraint and fiscal fudge sufficient to reassure the markets. In fact, one underappreciated point is that on current forecasts by the Office for Budget Responsibility, which take account of fiscal measures announced by the government up to and including the Spring Statement in March, the UK deficit is set to narrow sharply relative to many peers – not least France. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: Government Budget Balance (% of GDP) Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

The bigger risk may lie ahead. If Keir Starmer were replaced by a leader more inclined to spend and less concerned about market discipline, investors might be far less forgiving.

All eyes on people – and politics

Across the Atlantic, the fiscal outlook in the US also hinges precariously on people and personnel. Much now depends on Scott Bessent – a key moderating figure that markets see as one of their own – remaining in post as US Treasury Secretary. If he were to fall out of favour with President Trump and was replaced with someone with weaker market credentials then this could be the trigger for a sell-off in the bond markets. Likewise, if concerns about Fed independence continue to grow then this could push up long-term bond yields and feed into fiscal concerns. The decision on who replaces Jerome Powell as Fed Chair when his term expires in May next year will, needless to say, be critical.

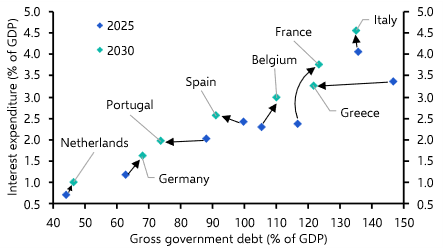

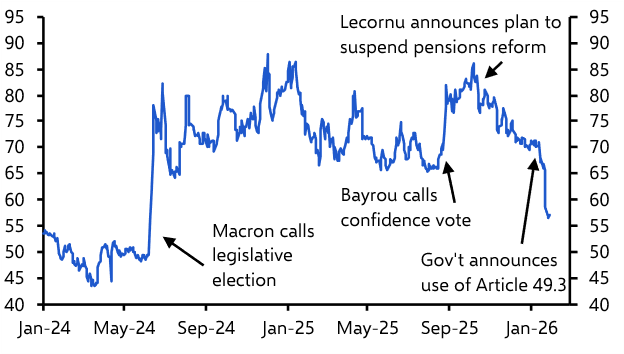

Finally, France appears to have settled into a Groundhog Day cycle of governments trying and failing to pass measures to narrow the budget deficit, and then being replaced by a successor that tries (and fails) to do exactly the same thing. Attention is slowly turning to the 2027 presidential election, whose outcome will be critical to determining not just France’s political future but also its economic and fiscal future.

If the centre fails to hold and far-right leader Marine Le Pen (or her alternate Jordan Bardella) becomes France’s next president, will she or he govern as an economic and political populist, or take a more moderate approach? A parallel here might be Italy’s Georgia Meloni, who campaigned as a populist but, in areas of economic policy at least, has governed as a moderate. This helps to explain why, despite its large debt pile, Italy has so far stayed out of the firing line. Another crucial question will be the extent to which France’s legislature, which operates significantly apart from the executive, might act as a moderating influence on a Le Pen administration.

These questions may be impossible to answer, but their answers will prove critical. As I argued a few weeks ago, the fiscal challenges facing advanced economies are essentially political. If a fiscal crisis does emerge in the years ahead, the trigger is likely to be political as well.

In case you missed it

- Amid the latest stand-off around US federal funding, Thomas Ryan explained why a US government shutdown would likely have limited economic impact – but also warned that Friday’s payrolls release could be affected.

- How will debt dynamics affect the UK and France in the coming year? This week we’re holding Drop-Ins to answer your questions about the outlook for these economies. Register to join the UK session on Wednesday and Europe briefing on Thursday.

- Our LatAm team wrapped up an extraordinary week in Argentine markets, but also assessed the likelihood of a thawing of US-Brazil relations when Presidents Trump and Lula meet this week.