Another squall in the bond market appears to have blown itself out. The summer lull had been interrupted by a jump in long bond yields, triggering warnings about surging government borrowing costs and fiscal crises across the advanced economies.

But roll on just a few weeks and yields have fallen back – the 30-year US Treasury yield has dropped around 30 basis points this month and is now back at levels last seen in late spring. So was all that fuss for nothing? Far from it.

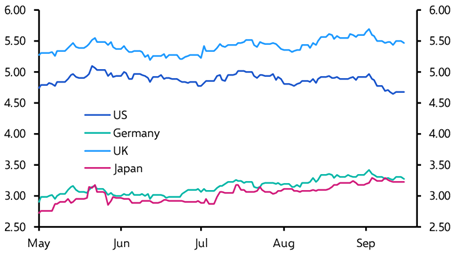

If nothing else, yields at the very long end of the US yield curve may have fallen substantially, but declines elsewhere have been much smaller. (See Chart 1.) More fundamentally, the fiscal concerns that contributed to the rise in long-dated yields over the summer have not gone away. A notable recent development has been in France, where efforts to repair the public finances have toppled the government for the second time in a year and where the new prime minister has hinted that he will water down plans for budget cuts next year.

|

Chart 1: 30-year Government Bond Yields (%)

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

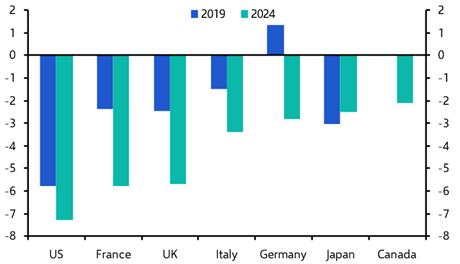

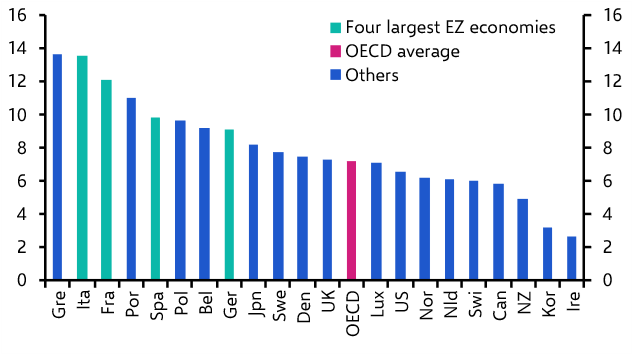

The prevailing view is one of budget deficits across the advanced world that have ballooned to eye-watering levels, and it is true that in most economies they have increased sharply since the pandemic. But there is enormous variation in the level of deficits. At one end sits Japan, where this year’s deficit is likely to be less than 1% of GDP – a marked decline compared to the pre-pandemic period. At the other is the United States, where the federal budget deficit is projected at 6% of GDP this year – even though the government is now pulling in around $30bn a month from tariff revenues. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: General Government Budget Balance (% of GDP) Sources: IMF |

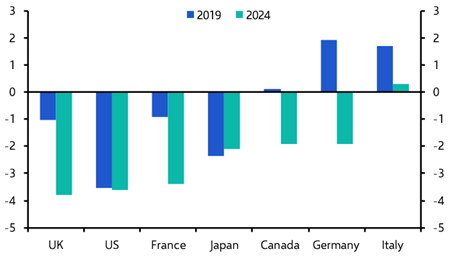

Higher interest rates have pushed up debt servicing costs and account for some of the rise in budget deficits in advanced economies. But primary deficits (i.e. those excluding debt interest expenditure) have also increased since the pandemic. (See Chart 3.) In other words, fiscal policy has become more supportive of aggregate demand.

|

Chart 3: Primary Budget Balance (% of GDP)

Source: IMF |

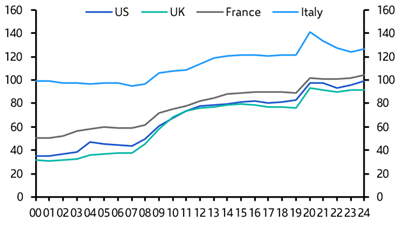

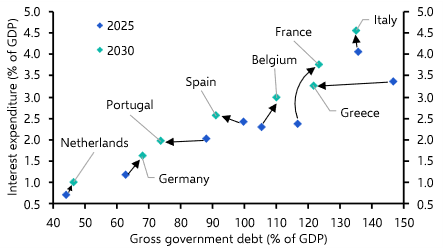

Crucially, this fiscal relaxation has occurred at a time when economies are running at or near full employment, meaning there is less scope to narrow deficits through growth. And, of course, debt ratios are significantly higher. (See Chart 4.)

|

Chart 4: Net Government Debt (% of GDP)

Source: IMF |

Not all risks are equal

The US stands out as the most extreme case, with a hefty deficit, a large debt burden, and little recognition on either side of the aisle that action is required. Yet Washington enjoys the “exorbitant privilege” of the dollar, which creates a latent demand for US Treasuries. The real fiscal weak spots lie elsewhere. Britain is a mid-sized economy whose recent inflation record has been worse than its peers and where the fiasco of Liz Truss’s “mini budget” still lingers in the minds of international investors. France, which is currently adjusting to its fifth prime minister since the start of last year, carries an even higher deficit and debt burden. And unlike the UK, its central bank does not sit directly behind the country’s bond market.

Some have suggested that both countries could soon be forced to turn to the IMF. This is nonsense. The Fund is a lifeline for economies that have borrowed heavily in foreign currencies and then lose access to capital markets. Britain borrows in sterling, a reserve currency which gives it significant room for maneuver. That flexibility may be on display this week, when the Bank of England is expected to keep rates on hold at Thursday’s MPC meeting but may also slow the pace of quantitative tightening to help contain the rise in long-dated yields. For all the noise in the bond market, there has been no collapse of confidence in the UK – gilt auctions have been running smoothly and short-term yields remain anchored.

Meanwhile, although France’s new government is facing higher borrowing costs, they are nowhere near crisis levels. And if Paris ever did require help, it would in the first instance turn to Brussels, rather than to the IMF in Washington.

Neither France nor the UK is staring down the barrel of a Greek-style debt crisis. What is needed is not an immediate and large fiscal retrenchment but a credible plan to bring down deficits and debt over time. But that is a tall order for politicians.

The UK Chancellor will set out fresh fiscal plans in the Autumn Budget on 26th November. Much will depend on whether the Office for Budget Responsibility, the government’s fiscal watchdog, sticks with its upbeat assumptions about Britain’s long-term growth. Even so, Rachel Reeves may have to rustle up savings or tax rises of £8-18bn to meet her rules – and of as much as £28bn if she wants to preserve the current fiscal buffer. Yet ministers have already U-turned on planned cuts to the welfare bill, while manifesto pledges have ruled out rises in the three big revenue-raisers: income tax, VAT and national insurance. France’s new government will likely be as unstable as its last. In both countries, right-wing populists are waiting in the wings with promises of tax cuts and lavish spending. If they were ever enacted, these policies could wreak havoc in markets and by extension in the French economy.

A political problem

Countries across the Western world are now paying the price for decades of economic policy mistakes stretching all the way back to the global financial crisis (GFC). After the GFC, governments embarked on premature and often self-defeating fiscal tightening. Coming alongside private sector deleveraging, this depressed aggregate demand and resulted in the weakest recovery from a recession since the 1930s.

That experience fundamentally discredited ‘austerity,’ leaving it so toxic that no party will go near it. But today’s economic backdrop is entirely different: most advanced economies would benefit from some measured, calibrated fiscal restraint.

The challenge is therefore not financial but political. In 1992, James Carville coined the now-famous quip “It’s the economy, stupid” to focus campaign efforts during Bill Clinton's run for the presidency. In today’s fiscal environment, “it’s the politics, stupid.”

Markets are still willing to fund deficits. But politics may frustrate the fiscal correction that is necessary over the medium-term. The danger is that this luxury will not last forever.

If politicians fail to act, markets will eventually do the job for them – and far more brutally.

In Case You Missed It

- How is the global economic order changing in Trump’s second term? Join us in London this Wednesday for an in-person event to hear our latest analysis on global fracturing, put your questions to our economists, and meet the team. Register here.

- Amid recent swings in bond yields and the surge in AI investment, Jennifer McKeown revisited our estimates of where equilibrium real interest rates (r*) are likely to settle over the long run.

- After yet another string of record highs for the S&P 500, James Reilly explained why – despite valuations and monetary easing expectations – we see even more upside for the index between now and end-2026.