Payrolls week invariably means another feeding frenzy in markets over the latest numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But this is a volatile series, and one that frequently gets revised. Any sensible central banker will remain above the fray to consider the broader health of the labour market. They have their work cut out for them.

What’s happening in global labour markets lies at the heart of the question about how far to raise rates. Keep policy too loose while inflation is still running hot and there’s a serious risk of wage-price spirals. But an overly tight policy setting risks pushing unemployment and deepening economic downturns by more than is needed to get inflation under control.

The challenge for central bankers – and independent macroeconomic forecasters – is that it’s currently difficult to tell what’s going on with labour markets, particularly with regards to the dynamics around labour supply.

Blame COVID

The pandemic created a huge shock to labour supply as workers moved firms, sectors, cities and even countries. Some dropped out of the workforce altogether.

Central banks trying to figure out the level of demand consistent with stable price inflation need to know what’s happening with supply. So understanding how this labour supply shock will play out is critical to forming a view about how far rates will need to be raised – and for how long they’ll need to stay there.

To do this, policymakers need to grapple with uncertainties around how the overall size of the workforce will evolve and around the ease with which available workers are matched to open vacancies.

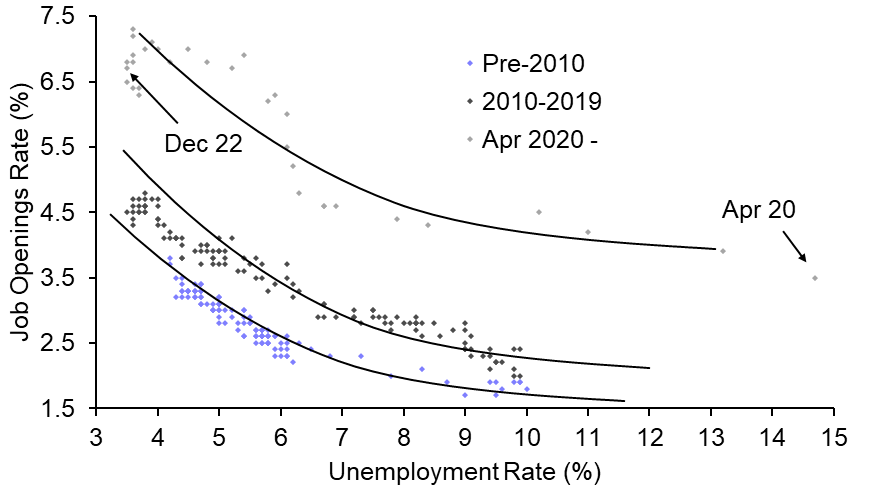

One consequence of the labour market dislocation brought on by the pandemic was a large fall in “matching efficiency” between firms and workers. Shifts in the sectoral composition of employment, skill requirements and the geographical location of employment all made it harder for firms to find the right workers to fill vacant positions. As a result of these mismatches, the so-called Beveridge Curve – which plots the relationship between unemployment and job openings – shifted upwards. (See Chart 1.) And firms had to increase pay to fill vacancies.

|

Chart 1: US Beveridge Curve (Vacancies & Unemployment) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

The great hope within policymaking circles is that these pandemic-related mismatches will eventually ease, the Beveridge Curve will shift back down and some of the upward pressure on pay will moderate. There’s historical support for this view.

Although today’s economic situation is frequently compared with the 1970s, it bears closer comparison with what followed the Second World War.

The end of the conflict saw large numbers of workers released back into the labour market from the armed forces. In the UK, seven million people were “demobbed” in the 18 months following the war’s end. At the same time, large numbers of women that had been employed as part of the war effort exited the labour market. And on top of all of this was the huge structural change in the UK economy as it shifted from a war footing.

The net result was a large increase in labour market frictions that made it difficult to match the supply of workers to available jobs. As a result, sectors including coal mining and agriculture faced acute labour shortages and wage pressures. It took until the end of the 1940s before these frictions had eased and the labour market was functioning more efficiently.

Given that labour markets are more flexible today, they should right themselves more quickly – though there isn’t much evidence of this happening yet. Indeed, while vacancies in the US had started to fall, they have rebounded in recent months. And while job openings in other countries have shown some signs of coming down, they remain at elevated levels.

Sick man, formerly of Europe

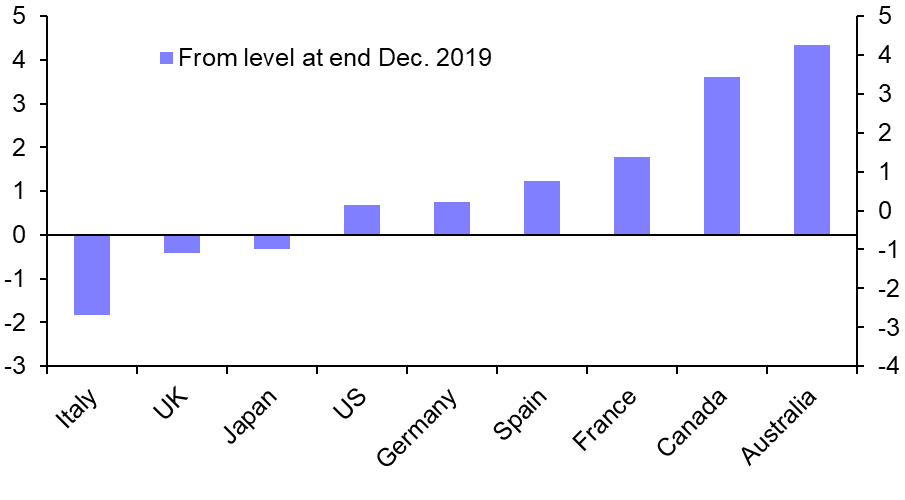

The same is true for the evolution of labour forces overall. This is something highlighted by Vicky Redwood, our Senior Economic Adviser, in recent analysis showing how the major advanced economies are having very different post-pandemic experiences.

At one end are Australia and Canada, whose labour forces are 3-4% larger than just before the pandemic started, helped by a strong recovery in immigration. (See Chart 2.) In the middle sit the US, Germany and France, whose workforces are 1-2% above their pre-pandemic level and, in the case of the US at least, are still growing at a decent clip.

|

Chart 2: Change in Labour Force (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

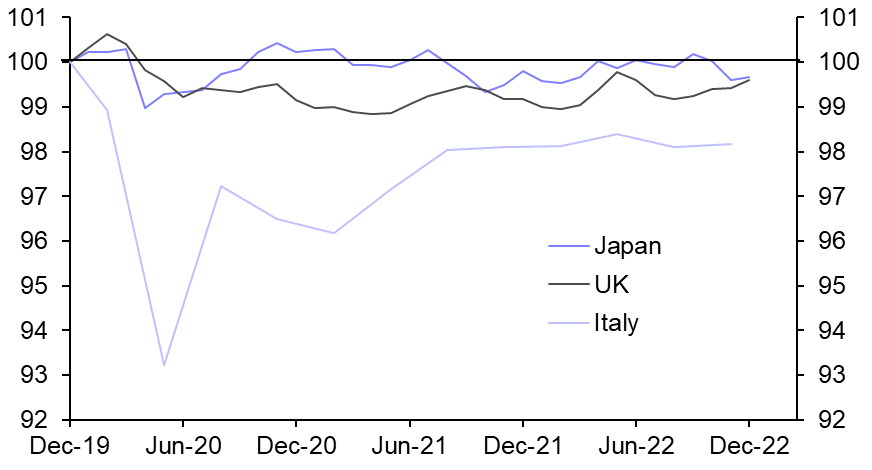

And at the other end of the spectrum sit Italy, Japan and the UK. The labour forces in all three countries are smaller than they were just before the pandemic. More worryingly, in contrast to economies such as the US, their workforces are now stagnating. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: Labour Force (Dec. 2019 = 100) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Italy and Japan’s labour supply issues are a partial reflection of their adverse demographics. In contrast, the UK’s are driven largely by a long term sickness crisis which is unique among major advanced economies and appears rooted in more fundamental pressures on the National Health Service and social care system. This will take time and deep reform to address – a much-trumpeted Brexit renegotiation won’t fix this.

So where does this leave us? History offers some support to the idea that central banks should eventually receive a helping hand in their fight against inflation from developments on the supply side of labour markets. However, the timeframe over which this may happen is extremely uncertain – and there are good reasons to think that supply-side problems will persist for longer in the UK and Italy than in other advanced economies. Accordingly, while supply-side improvements may eventually make life easier for policymakers, this will not prevent interest rates from having to rise further over the first half of this year. Food for thought as the payrolls frenzy commences.

In case you missed it:

- Adam Hoyes argues that equity risk premia suggest that investors may be becoming increasingly complacent about the outlook for the US economy.

- William Jackson and Giulia Bellicoso assess the inflation threat from EM labour markets.

- Marcel Thieliant argues that the Bank of Japan could abandon yield curve control as soon as this month.