The Thanksgiving holiday marks the point in the calendar where sell-side economists start to think about their “what to expect next year” pieces. We’ll be publishing our own contributions over the coming weeks, and will be hosting Drop-Ins for clients to discuss key themes and issues. Keep an eye out for invitations in your inboxes.

What happens in 2023 will be determined by the answer to three questions: will the world’s major economies fall into recession? Will inflation recede? And how far will central banks have to tighten policy?

On the question of recessions, economists offer a counterpoint to Paul Samuelson’s quip that stock markets have predicted nine out of the past five recessions. In contrast to the markets, economists almost never forecast recessions. This is partly because the usual state of affairs is for economies to grow. Recessions tend to occur once every decade or so. Accordingly, anyone forecasting a recession is betting against the norm – and the odds of being proven wrong are high.

I mention all this as background to saying that we are forecasting recessions in the US and most countries in Europe next year. Admittedly, the recent hard activity data have been more resilient than we had anticipated. But the survey data, including the PMIs released last week, are now consistent with falling output in the euro-zone and a marked slowdown in growth in the US across both regions. And there are good reasons to think that aggregate demand – and thus GDP – will be squeezed further over the coming year.

Ordinary vs extraordinary recessions

The most obvious reason to expect demand to weaken is that the full effects of the substantial monetary tightening over the past 12 months have yet to be felt. This will hit interest rate sensitive sectors (notably housing) particularly hard. In addition to the effects of tighter monetary policy, economies in Europe are also having to contend with a large hit to their terms of trade, which will continue to weigh on real incomes.

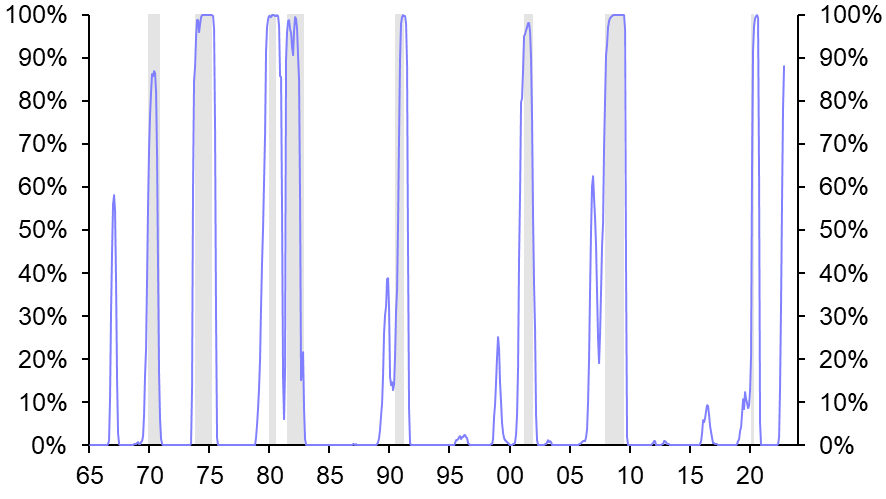

Our proprietary indicator now suggests there is a 90% probability that the US will be in recession in six months’ time. (See Chart 1.) It has never been this high without a recession following. When your macro analysis and proprietary models are telling you the same thing, it’s wise not to ignore them.

|

|

|

|

| Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

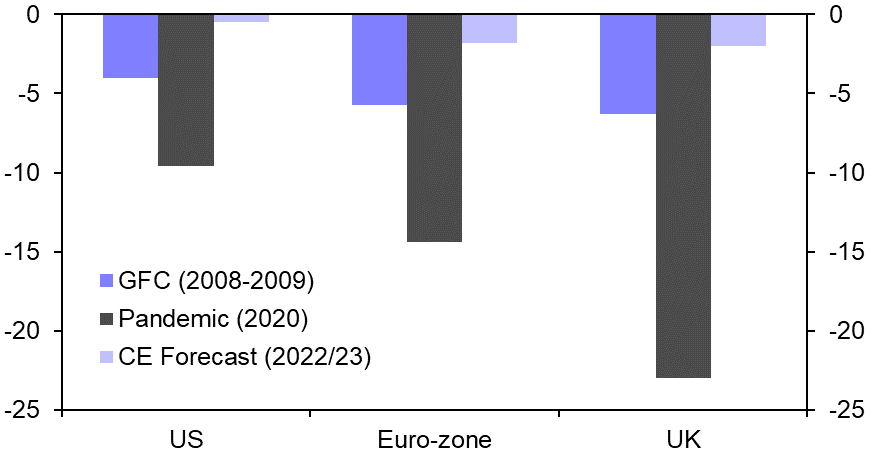

With that said, it’s important to stress that, in the case of the US at least, we anticipate a relatively mild recession. Our forecast incorporates a fall in GDP of about 0.5%-pts. The adverse hit to the terms of trade means that recessions in Europe will be deeper – we have pencilled in a peak-to-trough fall in output of around 1.5-2.0%-pts in the euro-zone and UK. But even here, the contraction in GDP will be much smaller than the past two recessions. (See Chart 2.) What’s more, a recovery is likely to commence over the second half of next year.

|

Chart 2: Peak-to-Trough Fall in GDP (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Our perceptions are naturally framed by recent experience, but when it comes to recessions the past two have been extraordinary: the recession in 2007-08 was caused by the largest financial crisis since the Great Depression, and the recession of 2020 was caused by a pandemic that shut down large swathes of the global economy. In contrast, the recessions we anticipate in 2023 are likely to be less extreme – think the 2001 recession in the case of the US, and the early 1990s recession in the case of the UK. This is not to underplay the significance of the looming downturn – or the pain that will be inflicted on households – but rather to underscore the importance of not viewing the next recession through the lens of the last one.

The outlook for China is equally gloomy but for different reasons. The surge in virus cases over the past fortnight has demonstrated how difficult it will be to relax quarantine rules and has put a huge dent in the view that zero-COVID might soon be ended. But the market commentary hasn’t caught up to the looming downside risks. One of the big tail risks for 2023 is that China’s government loses control of COVID and has to impose restrictions over a large part of the country to flatten the curve.

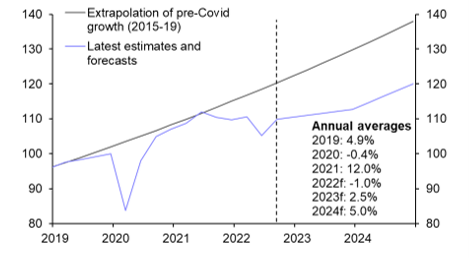

Even if these tail risks do not materialise, there are good reasons to expect China’s economy to struggle: the property downturn has further to run, and global demand for China’s goods exports will wane. Our forecasts, based on our China Activity Proxy, suggest that China’s economy will be around the same size at the end of 2023 as it was in mid-2021. (See Chart 3.) In other words, the world’s second largest economy will have experienced two-and-a-half years of lost growth. This is arguably the biggest story affecting the global economy today – and it is one that deserves much more attention.

|

Chart 3: CE China Activity Proxy (Q4 2019 = 100) |

|

|

| Sources: Capital Economics |

Better news coming on inflation

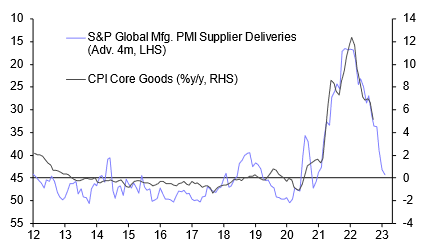

All of this adds up to a pretty gloomy economic backdrop. If 2023 is to bring better news, the chances are it is likely to come on the inflation front. There is already substantial evidence that goods inflation is slowing as shortages ease. Forward-looking indicators suggest that this is likely to continue through the course of the next year. (See Chart 4.) China’s slowdown will be a source of global disinflation and, while energy prices will remain elevated, energy inflation should slow.

|

Chart 4: US Core Goods Inflation & Supplier Deliveries |

|

|

| Sources: Refinitv |

There remain bigger questions over the path of services inflation (and non-goods core inflation), which is governed to a much greater extent by the balance of aggregate demand and supply in economies. Admittedly, there were encouraging signs of a slowdown in services inflation in October’s US CPI data. But one month’s data doesn’t make a trend. And while some of the labour market surveys point to a further moderation in wage growth, they are still signalling rates of pay growth that are inconsistent with central bank’s inflation targets.

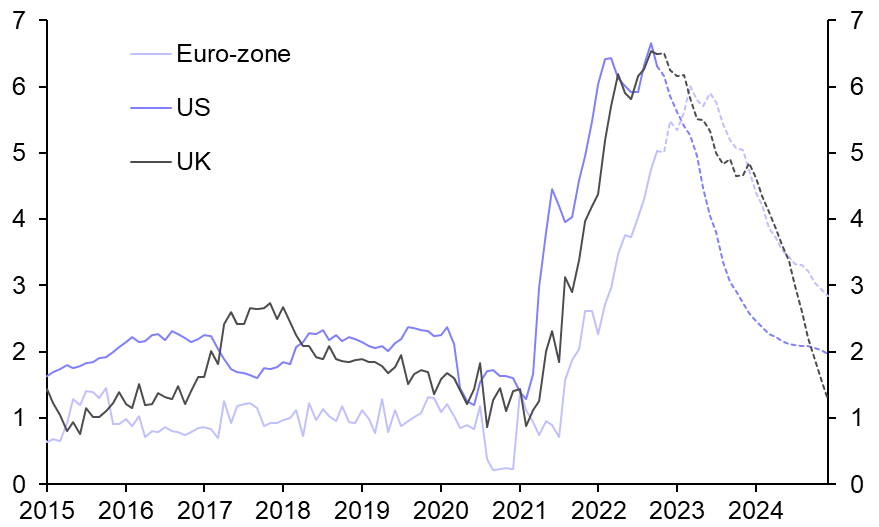

However, the picture should start to change over the course of next year. We expect unemployment to rise across advanced economies, which will take the heat out of labour markets. What’s more, as we set out in a recent Focus, there are reasons beyond the labour market to expect core inflation in the US to moderate. In this case, one month’s data should be the start of the trend. We therefore expect services inflation (and core inflation) to have moderated across developed markets by the end of 2023. The moderation will be more gradual in the euro-zone, where labour markets look especially tight. But the speed and extent to which headline and core inflation in the US falls could be one of the surprise stories of 2023. (See Chart 5.)

|

Chart 5: Core CPI Inflation (%) |

|

|

| Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

This brings us to the implications for monetary policy. The first point to make is that central banks across developed markets still have more work to do. This is particularly true of those in Europe, where core inflation will be slower to fall back and the pace of policy tightening has so far lagged that in the US. We expect the ECB to hike its policy rate to a peak of 3% by mid-2023 and the Bank of England to raise interest rates to a peak of 4.5% over the same period. But the tightening cycle is more advanced in the US and inflation looks likely to turn more decisively next year. We therefore think that the conditions will be in place for the Fed to begin cutting interest rates, albeit at a gradual pace, by the final quarter of the year.

If the past two years has taught us anything it is that shocks – COVID, the war in Ukraine, and so on – can appear from left field to upturn even the most considered economic forecasts. The effects of these shocks are still rippling through the global economy and mean that any forecasts for 2023 are subject to more uncertainty than usual. At the same time, new shocks may materialise: the rapid tightening of monetary conditions could expose financial vulnerabilities in unanticipated places, EM private debt vulnerabilities are building and the fracturing of the global economy that we explored in our annual Spotlight report means that geo-politics has returned as a source of economic and financial risk.

Upside risks exist too. Inflation could fall further than we anticipate, particularly in Europe, reducing the need for further monetary tightening. This could be helped by a larger-than-anticipated drop in global commodity prices. Meanwhile, the remaining COVID-era supply distortions could unwind faster and further than we expect, which would boost global production.

The one thing we can be reasonably sure about is that the economic backdrop is likely to look and feel very different in a year’s time. Wind the clock forward 12 months and our sense is that 2023 will have been a year of recession in advanced economies, continued weakness in China, and falling inflation everywhere, but particularly in the US. The prospect of a moderate recovery commencing in the second half and the Fed cutting rates by the end of the year means there’s light at the end of the tunnel. But as 2022 draws to a close, the tunnel looks pretty long.

In case you missed it:

- With the Chinese government’s zero-COVID policy under severe strain, we’re holding a briefing about the domestic and global consequences. Register here for Tuesday’s 15:00 GMT online session.

- Will Friday’s non-farm payrolls report show that more steam came out of the US labour market in November? Here’s what to expect.

- The UK government has started making payments to the Bank of England as part of their indemnity agreement. It’s another sign of how higher rates are eroding the UK’s public finances.

- And don’t miss our latest podcast episode, which includes discussion of some the themes in this note but also the risks posed by rising rates to EM corporate and household debt.