Last week saw a flurry of second quarter GDP releases covering economies from Korea to Mexico and the US to the euro-zone. In many ways the data are already old news – they cover a period that started when many economies were still in lockdown and ended before the rapid spread of the Delta variant began to cast a cloud over the outlook. What’s more, as we’ve noted before, the different approaches taken by national statistics offices to measuring output through the pandemic has made it more difficult to compare GDP data across countries.

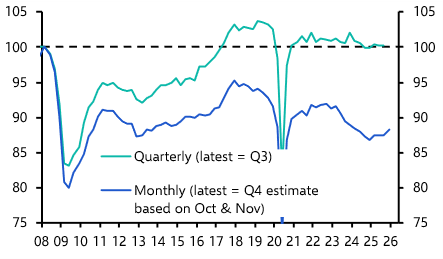

Still, distortions and timeframes aside, the GDP data still contain useful information and the bottom line from last week’s figures was that the world’s major economies have staged a pretty impressive recovery. Despite having suffered the largest peak-to-trough fall in output on record during the early stages of the pandemic, the US has now returned to its pre-virus level of GDP. And while a combination of smaller stimulus and longer lockdowns mean that the euro-zone is still around 3% below its pre-virus level of GDP, it’s on track to get back to its pre-pandemic level of output by Q4 of this year.

This impressive recovery forms the backdrop to our latest Global Economic Outlook, which we published last week. This in-depth, quarterly analysis of the near to long-term outlook for advanced and emerging economies contains five main messages.

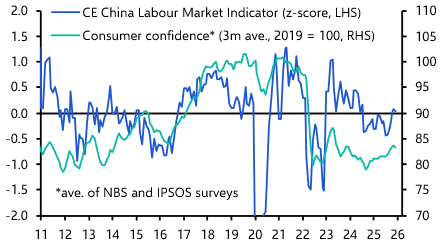

The first is that growth in most major economies is likely to slow over the coming quarters. This partly reflects continuing constraints on the supply side of economies, particularly in the US. But the main reason is that most economies have already recouped much of their lost output, meaning growth will inevitably soften. China’s economy is already slowing, and the US recovery is likely to slow from Q3 this year. The euro-zone and UK will follow later in the year. All of that means that global GDP growth will be weaker in 2022 compared to 2021. But it’s important to get this slowdown into perspective – it doesn’t mean that the recovery is stalling, it means that economies are normalising.

Second, the virus remains the biggest threat to the outlook. We don’t think the rapid spread of the Delta variant will derail recoveries in advanced economies, but it poses a bigger threat to those emerging economies – particularly in Africa and Latin America – where vaccination rates are lower. And even if the Delta variant does not derail recoveries, its spread is a reminder of the fact that we are likely to have to live with COVID for the long term. Vaccines may have weakened the link between infections and hospitalisations for now but, as efficacy wears off and new variants emerge, that may not remain the case. The virus is likely to remain at the top of our list of risks for some time to come.

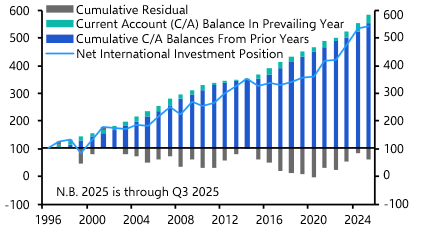

The third message is that we are likely to see a shift in consumer spending patterns over the coming quarters. The pandemic caused a pivot in spending away from services and towards consumer durables. This boosted exports (and GDP) in economies such as China, Korea and Taiwan, where many of these goods and their components are produced. As economies reopen, spending is likely to shift away from consumer durables and back towards services. The need to rebuild inventory along the supply chain will cushion the hit to export demand in Asia, but this will nonetheless be a headwind to growth in these economies in 2022.

The fourth point is that headline inflation is likely to drop back in every major economy next year – but core inflation is likely to remain elevated in a handful of economies, notably the US. The fall in headline rates may help to take some of the heat out of the debate around inflation, but the stickiness of core rates in some places means it’s not going to disappear entirely. We’ll have more to say about the long-term inflation outlook in a major series of work coming in the autumn.

The final message in our Outlook is that policymakers are likely to keep support in place throughout 2021-22. But the Federal Reserve will begin tapering asset purchases early next year and gear up to raise rates in 2023, while the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan maintain their relatively accommodative policy stances. That in turn should lead to a modest rise in US government bond yields, which in turn should support the dollar.

Stepping back, then, what emerges from a complex and nuanced set of country forecasts is a global economy that has bounced back remarkably quickly from the biggest shock since the Second World War. Growth will slow over the coming quarters, but this is an inevitable consequence of the rapid rebound beforehand. All of this lends weight to our view that, unlike previous crises, the pandemic will not set economies on a lower path of output over the long-term.

The Delta variant continues to challenge economic recoveries, particularly among emerging markets, while the emergence of new strains of the virus is likely to remain a long-term concern. But even against those considerable uncertainties, our latest Global Economics Outlook shows why, after last year’s unprecedented shock marking the start of our pandemic age, there’s cause for optimism about the global economy.

PS: Our Q3 Global Economic Outlook, ‘Pandemic rebound peaks but recovery story still intact’, is available as part of our Global Economics service. If don’t already receive this and you would like to find out how to access this research, get in touch.

In case you missed it:

- Our Senior Markets Economist, Jonas Goltermann, argues that the bond market is sending a gloomy signal that’s difficult to square with the economic outlook.

- The latest reading of our proprietary China Activity Proxy shows that growth in the world’s second largest economy is now slowing.

- Our Senior Markets Economist, Oliver Jones, argues that growing policy risks add to the reasons to think Chinese equities will underperform.