It is now accepted wisdom that in times of crisis fiscal policy should work hand-in-glove with monetary policy to deliver support to the economy. In the depths of the COVID crisis this meant huge fiscal relaxations in advanced economies being effectively financed by asset purchases by central banks. This cushioned the collapse in activity and paved the way for the strong recoveries that are now underway across the developed world.

But relatively little has been said about how fiscal and monetary policy should work together in a post-COVID world. Concerns are now building that the rapid snap-back in activity will generate inflation pressures, but the debate so far has focussed on how central banks should respond if this materialises. In contrast, there has been no discussion about the role of fiscal policy. Could it make a more active contribution to demand management?

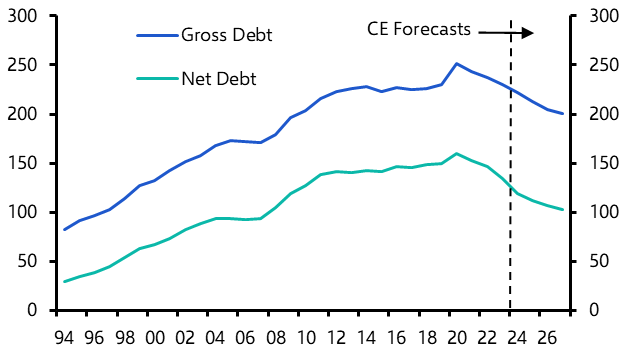

At first sight, the idea seems appealing. If we are right in believing that the long-term economic scarring from the pandemic will be limited, then budget deficits should close as economies return to health. But one legacy of the pandemic will be substantially higher government debt burdens. In most advanced economies government debt is now running at its highest level relative to GDP since the Second World War. (See Chart 1.) These elevated debt levels do not pose an imminent threat to economic or financial stability. But if interest rates rise then the cost of servicing these higher debt burdens will increase. More fundamentally, if the past eighteen months has taught us anything it is that the future is inherently uncertain. It would be a sensible ambition to bring government debt ratios down over time.

Chart 1: Government Debt (% of GDP)

Source: National Sources

This raises the intriguing prospect that, should inflation become a problem and aggregate demand need to be restrained, fiscal policy might do the heavy lifting. It’s worth keeping in mind that the steady fall in government debt ratios following the Second World War was achieved through a combination of fiscal restraint, sustained economic growth, modest inflation and some forms of financial repression that kept a lid on real interest rates. It’s possible that history now repeats itself and a similar approach is pursued by policymakers in a post-COVID world.

The problem is that relying on fiscal policy as a primary tool of demand management has been tried before and found wanting. Two issues exist in practice. The first is that while some elements of tax policy, such as sales tax or VAT rates, can be changed overnight, some tax rates and most government spending plans are set according to annual or multi-year frameworks. This makes fiscal policy less responsive to changes in the real economy than monetary policy.

The second problem is that fiscal policy decisions are (rightly) made by democratically elected governments and are often taken with political rather than economic objectives in mind. Accordingly, while it may make economic sense for fiscal policy to do the heavy lifting as pandemic-era support is reined in, the political reality could make this difficult.

It seems likely that governments are going to come under growing pressure to increase spending over the coming years. Some of this pressure is a direct response to deficiencies revealed by the pandemic, for example around health and social care, and some stems from a growing urge to tackle new issues, the biggest of which is climate change. Underpinning all of this is a sense that the pandemic has altered the perceived power and reach of the state. While these are deserving causes, it goes without saying that governments won’t simultaneously be able to increase spending and run tighter fiscal policy without significant increases in taxes. This too is likely to prove politically unpalatable.

For these reasons it is likely that monetary policy will remain the primary tool of demand management in advanced economies. However, this does not mean that there is no role for fiscal policy. On the contrary, two priorities stand out. First, in the near-term governments and finance ministries should take a fiscal equivalent of the Hippocratic oath: that is to say, fiscal policy should first do no harm. The huge relaxation of fiscal policy was the correct response to the collapse in activity and spending caused by the pandemic. But it should be withdrawn as economies return to full employment and any additional spending on new priorities should be funded through (and justified by) higher taxes.

Second, if at some point in the future economies start to overheat and inflation takes off, governments and central banks should co-ordinate a policy response in the same way that they did when the crisis hit. As part of this, governments should commit to a sizeable tightening of fiscal policy in order to ease the burden on central banks and monetary policy. While political and practical difficulties may prevent fiscal policy from supplanting monetary policy as the primary tool of demand management, it could still play a critical role in heading off a sharp and destabilizing rise in interest rates.

Going one step further, both of these points could be brought together in a form of fiscal “forward guidance”. Governments should make clear their intention to support economies through the recovery, but they should also commit to bringing down public deficits and debt over time once economies return to full employment. And they should pledge to tighten policy more aggressively if inflation or inflation expectations become unanchored.

Fiscal and monetary policy worked in tandem with one another to support economies through the pandemic. As crisis turns to recovery, central banks cannot now bear the policy load alone: governments need to start articulating a role for fiscal policy in a post-COVID world.

In case you missed it:

You may have noticed that we have launched a new client website. We have also introduced several additional client features in recent months including:

- A new Forecast Hub, which contains all of our key forecasts and a high-level summary of our views on key economies;

- CE Interactive, our new data and analytics tool; and

- Capital Calls, which outlines a highest conviction macro calls and their market implications.