Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 19th of January and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, we grab the bull by the horns, unpack our 2024 S&P 500 forecast and explain why we see another year of big gains for US stocks. But first, Neil Shearing, Group Chief Economist, is with me to run through the big macro and market stories. Hi Neil.

Neil Shearing

Hi, David.

David Wilder

There's much we could be talking about, but let's face it, it's got to be central banks and inflation given we've seen this past week, doesn't it? Lots of unease about inflation, questions about how eager central banks are going to be to start cutting rates. General pushback in terms of near-term rate cut expectations. Bring us up to speed on how expectations have shifted and whether this is a justifiable reality check.

Neil Shearing

I think there's two components to this, right? There's what central bankers have told us and the message they've been sending over the last week or so and how markets have responded. Now, on the message that we've had from central bankers, in the US we had that speech from Christopher Waller, who has been on the more hawkish side of the spectrum for the past two years, but then was perhaps one of the first to start talking about rate cuts more recently. That was widely interpreted, at least in the media, as being hawkish and in particular dampening down expectations for aggressive rate cuts this year.

If you look at the content of the speech, I don't think it was quite as hawkish as some of the headlines had made out. What he was really saying, I think, was, “I anticipate we'll be cutting interest rates this year, the timing of the first cut is uncertain, the magnitude of the eventual cuts and scale of easing is uncertain too, but it's unlikely to be as substantial as it has been in the past”. But then think about what the last few easing cycles have looked like: they've been extremely substantial coming in the run-up to the global financial crisis and then following the pandemic. So they've been unusual in the scale of the policies that we've seen. So just saying that we don't anticipate we'll be loosening as much as we have done in the past, I don't think it's quite as significant as some of the headlines may have suggested. So perhaps I would push back a little bit on the idea that the Waller speech is quite as significant as some in the market have interpreted.

David Wilder

But we’ve also had pushback from ECB Governing Council members in the past few days as well in terms of how quickly they are willing to move to cut rates as well. We've got the ECB meeting this coming Thursday. What do you think we can expect from the Governing Council?

Neil Shearing

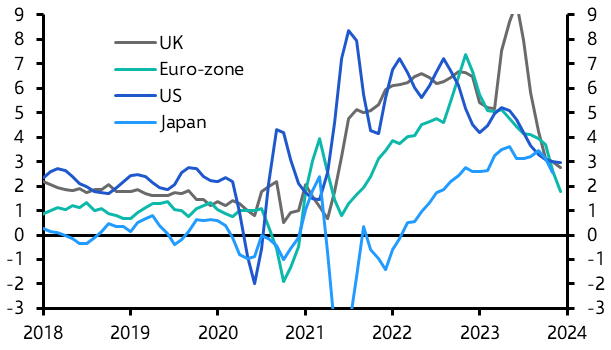

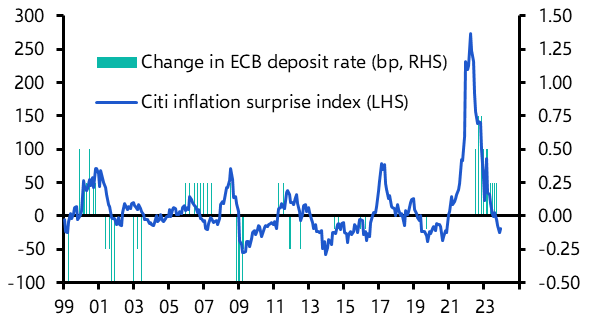

Yes, I mean just on the messages that we've had from policymakers from the ECB over the past week or so, I think perhaps they are a bit more significant for a couple of reasons. One is that they've spoken in unison. So we've had several policymakers essentially saying the same thing, which is putting a stake in the ground around the summer has been the most likely date that they would start to cut interest rates. The second reason why I think it's significant is they've also started to flesh out the types of things they need to see or will wait for before they start to loosen policy, cut interest rates. And in particular, I think there's a sense that some policymakers want to see further evidence of a slowdown in wage growth. And we know that in the euro-zone, that data is released with a lag. Some policymakers have indicated that they will want to wait for the Q1 wage data, which will include the results of wage bargaining and wage settlements in the first quarter of the year for 2024. But that's not arriving until May. So that perhaps makes June a bit more likely than the April that we've got pencilled in for the first rate cut. So perhaps a bit more significant in terms of the communications in terms of the timing of the first rate cuts in the euro-zone from statements over the past week or so. And I suspect that will be mirrored in the communications around the coming week's Governing Council meeting. I think the press statement that accompanies the meeting will be pretty much a copy and paste job from December's Governing Council meeting. But in the press conference that follows, I suspect we'll get the same message that has been filtered through policymaker speeches over the past week or so, I suspect we'll get those reiterated in the press conference. I think the key is that they'll be emphasising that we remain, however, data dependent. And that I think is absolutely critical because if you look at the data in the euro-zone – particularly the inflation data – yes, the year on year rates remain elevated, but the month on month rates and the three months on three month annualised rates are falling like a stone. So we've had lots of discussion, haven't we, in the media about whether the “last mile” is the hardest in terms of the disinflation process. But if you look at services inflation, three months on three months annualised in the eurozone, that's now below 2%. The core inflation, three months or three months annualised rate, that's just above 1% now. And non-energy industrial goods, three months on three months annualised rate has been negative recently. So if you look at the month-on-month rates of inflation, they're falling like a stone. So if the ECB really is data dependent, then yes, they've been indicating perhaps a June hike looks more likely, but it's possible, I think, that we're still going to an earlier move.

David Wilder

Do you think a lot of this noise comes down to this idea that central bankers, they want to be more Paul Volcker-ish than Arthur Burns-ish and that they want to decisively squash inflation, they need that confidence, they don't want to make that mistake of easing their foot off the break too soon?

Neil Shearing

Yes, I think there's something to that. And if you're going to push that view further, you can say, well, look at the experience in the 1970s where inflation came down and then inflation started to fall and then it was resurgence again a couple of times actually. So I think you can create a case for being more cautious. But then if you think about what was driving that experience in the 1970s, it was really kind of twin oil shocks. Now fast forward to today, inflation hordes could argue, well, there's the risk exactly that plays out given events in the Red Sea and in the Middle East over the past month or so. But as we've set out in our research, I don't think at this stage that poses a really substantial upside risk to inflation. Now, clearly if that escalates much further, it could do, but the moves in energy markets that we've seen don't amount, I think, to a substantial risk to inflation over the coming months. So yes, perhaps trying to invoke Volcker and ensuring that they don't go down as the next generation of Arthur Burns. But I think if you look at the incoming data, not just in Europe, actually in the US too, the month-on-month inflation numbers are really falling quite sharply. So these elevated year-on-year rates are really just a product of what was happening 12 months ago, six to 12 months ago rather than what's been happening over the past three to six months.

David Wilder

Christopher Waller in that speech you were talking about, he called the 10-year Treasury yield at 4% still restrictive. But then we had ECB minutes this past week, which suggest the council members thought moves in the Eurozone bond market in December basically had done some of its easing job for them. So what do we make of these two contrasting takes on the dramatic moves in bond yields that we saw at the end of last year?

Neil Shearing

Yes, I think there's a couple of things going on here. I think in absolute terms, Waller is right. Financial conditions do look pretty tight to me. Certainly it's the case that if we look at where real interest rates are, and for that matter nominal interest rates are, they're substantially above our estimate of where the neutral rates lie in the US, but also in the euro-zone and for that matter in the UK. So I think in absolute terms, yes, monetary policy is still tight, financial conditions are still pretty tight. The comments from the ECB though about yields falling back and whether or not that's doing some of the easing for them, that brings us back to this idea, doesn't it, of the Maradona effect that was talked about before on this podcast by Mervyn King, the former governor of the Bank of England. This harks back to that great goal that Maradona scored in the World Cup in 1986. He ran in a straight line. The England defenders got out of his way because they thought that he was going to move one way and actually he didn't move at all. And the idea is that there's a parallel here with monetary policy that if central bankers send a signal to the bond market, they will do the easing for them. But I think the truth of that has always been that central bankers then have to follow up with the action. And the fact that they've then pushed the bank back a bit on this idea. They haven't actually been cutting interest rates. We've seen yields back up a bit over the past month or so since that big rally in the bond market at the back end of last year.

So, I come back to this point all the time that yes, central bankers can kind of nudge bond markets around with a speech here and a press statement there, but ultimately what matters is what they do with policy, where they set policy. And if they don't follow up their words with actions, then the markets will just readjust. And that's what we've started to see a bit over the past week or so.

David Wilder

That's a great segue to talk about China, where the market has been waiting for months for the government to announce stimulus to help support this very fragile recovery. And not enough stimulus has been forthcoming. We had that China GDP report on Wednesday. That really set the cat among the pigeons – maybe it was a panda – but lots of attention on that full year growth number, lowest in three decades, et cetera. On the other hand, official Chinese GDP data is murky, to put it politely. So what's our message around the China outlook near and long term?

Neil Shearing

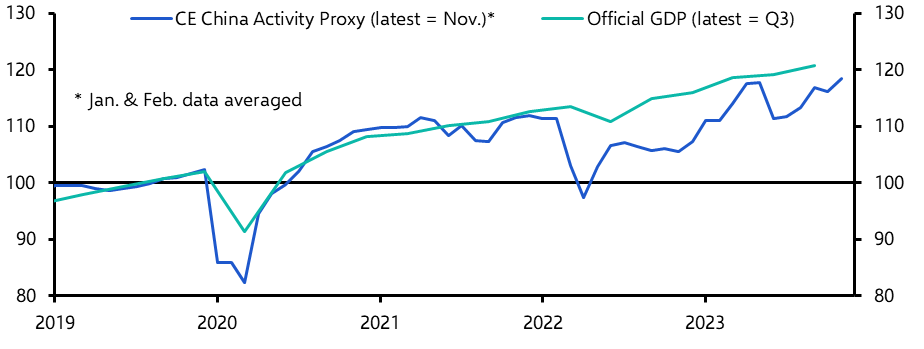

Yes, you're right. Lots of focus on that year-on-year number. I mean, the year-on-year number doesn't really tell us much anyway, but there's a parallel here with what we've just been talking about with inflation. Year-on-year GDP growth is often a product of what's been happening months and quarters ago, rather than what's been happening in economies recently. I think more fundamentally though, you're right, there are now widespread concerns, broadly accepted concerns, over the accuracy and reliability of the Chinese GDP data. Not the nominal GDP data, the real GDP data. That's what we're talking about when we talk about growth rates, is the real rate of growth. We have our own measure of Chinese economic growth, the China Activity Proxy.

That's been telling a very different story actually. The official GDP data had a bit of strength in Q3, q-on-q, but then weakness in Q4. We have it the other way around, that Q3 was a bit soft, but Q4, there has been a pickup in activity. I think that's consistent too, with some of the monthly activity data that we get from China, but also if you think about what's been happening with policy stimulus. We had an injection of policy stimulus in August, September time. That's now been feeding through into activity in Q4. So, our take is that actually there's a bit of a cyclical recovery underway in China at the back end of last year. And we suspect that will continue into the first few months of this year. It's stimulus driven, it's being driven by the usual sectors, particularly kind of infrastructure. We don't think it's sustainable. We still think there's kind of deep structural issues. But the fact that the narrative has really been about weakness at the end of last year rather than actually a cyclical rebound, I think reflects the fact that the official GDP data not very reliable. And actually you need to get an independent read on what's going on in China's economy if you really want to understand what's going on.

David Wilder

Neil Shearing there on our China Activity Proxy. The newest reading of this proprietary measure is out this coming week. You can find more about the CAP on our China economics page and Julian Evans-Pritchard, our China head, is going to be on a Drop-In – that's one of our short form online briefings – this coming Thursday, 8am London, 4pm Singapore, to talk about the CAP along with Marcel Thieliant, our Japan head, who will be briefing on the Bank of Japan's January meeting and explaining why we think a one-off rate hike is coming in March. Details about this event, which is our monthly Asia Drop-in on our podcast page. I'll also post that inflation analysis about the last mile that Neil was talking about on the podcast page. It's our Global Inflation Watch. It gives a much clearer view of what's happening with inflation than the headline numbers that are being reported elsewhere. On the ECB, our Europe team is going to be all over that Governing Council meeting on Thursday. Their week ahead preview is already out. I'll link to that on the page. On the day itself, expect a rapid response within minutes of the decision. More in-depth analysis coming after Christine Lagarde's press conference. Our markets team is also going to be on hand that day with insight on what's happening with bond yields and FX and expect follow-up analysis in their end-of-week reports on Friday. Then the following Thursday, that's February 1st, our Europe team is going to be joining our UK and US economists for a Drop-in to discuss that ECB decision in the context of the Fed and Bank of England meetings that are happening that week and what all of these decisions signal about the timing and scale of rate cuts for the coming year. I'll put registration details for that on the podcast page. All this content is available with CE Advance, our premium platform, where you can also send questions directly to the team via a Q&A function and get an answer pronto. Details about Advance at capitaleconomics.com/ce-advance, that’s /ce-advance.

Now, after a bumpy year for US equities, what does 2024 hold in store? More outsized returns according to our global markets team. They've just published an in-depth explainer around their very bullish forecast for the S&P 500. I spoke with John Higgins, our Chief Markets Economist, about our view. I started by asking him to outline our S&P forecasts.

John Higgins

Well, we've got some pretty punchy forecasts for the stock market this year next, David. We've actually had them since around the middle of last year when we became much more upbeat about the outlook for equities given our view about the possibility of a bubble forming around artificial intelligence. So those forecasts will be made then that we're sticking to our 5,500 for the S&P 500 for the end of this year, and 6,500 for the end of next year.

I'd say those are considerably above sort of consensus forecasts. A lot of people expecting a much tougher year for the S&P 500 this year after a very strong performance in 2023.

David Wilder

Yeah. And that implies sort of roughly 12% higher for the S&P this year relative to where it is now and another 18% in 2025. Talk about how we get to 5,500 this year. Let's start with the fundamental sides of things. What does a slowing US economy mean for the earnings outlook? How does that support your view of where we think the S&P is going?

John Higgins

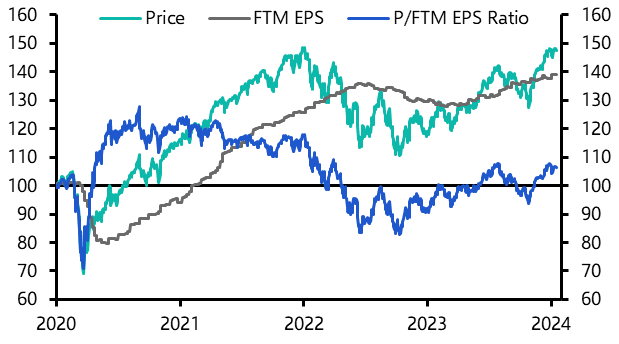

Clearly it’s a challenge. We had been quite concerned last year that the US economy would fall into a recession, particularly earlier last year amid the mini-banking crisis. And it's quite clear when you look back at past cycles that earnings in the stock market tend to really struggle when the economy is not doing badly and often will fall quite significantly during a recession. And we were of the view that the market hadn't been braced essentially for the recession that we felt that was coming. And that sort of, if you like, underpinned a view that we had for the first half of last year that actually the stock market would struggle for a while until such time as that sort of mild recession was over. And typically, if you look back at recessions in the US over the last 60 years or so, you tend to find that drawdowns in earnings are pretty significant in and around recessions, you know, perhaps even 20% or so in real terms on average, even if we strip out the global financial crisis where it was obviously pretty bad. But even allowing for high inflation that we've seen recently, we never really saw that scale of drawdown, barely got into double digits in real terms, the decline in 12-month trailing earnings per share for the stock market. And that's turned around now as well. So analysts really really not envisaging at all a deterioration in earnings as we move forward. I think we're really simply sympathetic to that. We still envisage the US economy experiencing a soft patch in the first half of this year, but we're now minded to think that it's going to skirt a recession. And in those circumstances, we're not envisaging another big drawdown in earnings. I should say, though, that our forecast for the stock market to make the big gains that you were describing there isn't really premised on the idea that earnings are going to take off. It's more about the valuation of the stock market picking up further from its current level. We do see some scope for further growth in earnings, but not dramatic from here.

David Wilder

I'm glad you raised valuations. Let's get on to that. But perhaps via the Magnificent Seven, these stocks that have been identified as driving so much of the gains, certainly last year. A lot of talk these days about how these stocks, so Nvidia, Microsoft, etc. are ‘priced for perfection’. How much is baked into their valuations and to what extent does the story that we're telling on these stocks continuing to outperform, how much of that ties into your forecast for this year and next?

John Higgins

Well, I think when it comes to the valuation of the stock market, there's no doubt that it is high by the standards of the past. But I think we do need to think about a couple of things here. First of all, I don't think you can think about the valuation of the stock market itself in isolation. You also have to consider the valuation of competing assets and bond yields are, despite rebounding considerably over the last year or two since the Fed started tightening policy, they're still generally much lower than they were in decades past. The so-called neutral level of interest rates still considerably lower.

So I think there is a case actually that the valuation of the stock market, you know, in equilibrium, if you like, or in normal times, ought to be higher than perhaps it was when we're comparing it with what it was on average in, you know, over previous decades. I think it's clear that the Magnificent Seven have been responsible for a lot of the increase in the S&P 500 and indeed in its valuation over the last year or so, particularly in the first half of 2023, when we started seeing enthusiasm around AI growing.

As far as the future’s concerned, we wouldn't be surprised if the sectors in which the Magnificent Seven resided, so that's Information Technology, communication services, consumer discretionary, that they continue to lead the charge generally in the stock market, pushing it higher and being responsible, if you like, for a further increase in its valuation. But at the same time, we feel that other sectors of the stock market, whose valuation is a lot lower and who've really lagged so far during this rally, are poised to do reasonably well as a sort of rising tide, if you like, lifts all boats.

David Wilder

So what about bubble risks? How does where we are now compare to the dot com bubble in the late 90s?

John Higgins

When we look actually at the stock market more closely, we don't really see it being asrichly valued as it has been in past bubbles. So if you were to compare, for example, the valuation of the stock market today with the valuation in the second half of the 1990s, we're not at that peak level yet. We've got, we think, quite a way to go before we reach the sorts of levels of valuation that we saw right at the end of that bubble before it burst. Also, although we didn't have such a concentration of stocks driving the S&P 500 higher in the second half of the 90s as it wasn't so clear, I think, to investors who the real winners would be from the transformative technology of that day. If you look actually at a sort of slightly broader subset of the stock market, let's say the top 100 companies in the S&P 500, you actually see that became even more concentrated that rally then than we've seen over the last year or so in the stock market. So I think there is scope for this sort of concentration rally to continue.

Also though, we think that there's scope for a sort of broadening out of the stock market rallies and we'll see more sectors of the stock market doing well, just like they did in the second half of the 1990s when again information technology led the charge. So again, when we look, sort of take a holistic look at the valuation of the stock market and try to factor these two things in, our view is that there is still scope for its valuation to inflate further in the next two years, until such time as it reaches a similar sort of level that we saw right at the end of dotcom mania, sort of in the late 1999, early-2000s.

And indeed, when you look actually at our forecast for, say, the end of 2025, 6,500 for the S&P 500, to get to that sort of number, you could, I mean, obviously there's lots of different ways you could get to that sort of number, but one way of thinking about it is imagine the valuation of the stock market just on a simple price to forward earnings ratio got up to the level it reached in the dotcom bubble, which was just shy of 25. If we got to that number of 25, or we're just shy of 20 now, you could easily see that 6,500 being reached. All you'd need to see happening on the earnings front is a forward 12 month earnings number of around $260. That compares to a number now of around $243. It's not a huge increase from where we are on the earnings front.

So as long as you get this combination that I've been describing of some growth in earnings against a backdrop of the economy that's not as bad as we thought, you know, a recession not actually happening, even if it hits a soft patch for a while, things improve, and evaluation is growing against a backdrop of growing enthusiasm and hype around AI. We think, you know, those targets that we've got, this forecast that we have, could well be met before the bubble bursts.

David Wilder

That was John Higgins on AI bubbles and stock market returns. His report will be on the podcast page and I'll be talking to John and James Reilly from our markets team this coming Wednesday 24th at 10am Eastern, 3pm London about our markets outlook and our new financial market dashboards. These are launching in the coming week and take our forecast much further, giving you a fully interactive guide on what to expect across major asset classes in dollar, euro, sterling and local currency terms. Again, details about that briefing on the podcast page. But that's it for this week. Next week we'll be talking about the macro and market impact of rising Middle East tension, particularly the impact on shipping and the inflation risks around that. But until then, goodbye.