The questions that come up most often in client meetings tend to offer a good barometer of the issues preoccupying investors. Over the course of this year, the focus has shifted markedly. The first half was dominated by trade tensions and tariff risks; the second by the challenges, opportunities and risks posed by artificial intelligence.

We’ve written extensively in recent years about the economic and market implications of the AI revolution (see here). But in recent weeks, two questions have come to the fore. The first is whether the rapid rollout of AI is already eroding demand for labour – particularly among younger workers – and risks ushering in a period of structurally weaker employment. The second is whether the surge in capital spending by the so-called hyperscalers and major technology firms represents a rational response to opportunity, or a classic case of overinvestment that stores up financial trouble for later.

AI not the main driver of labour market softening

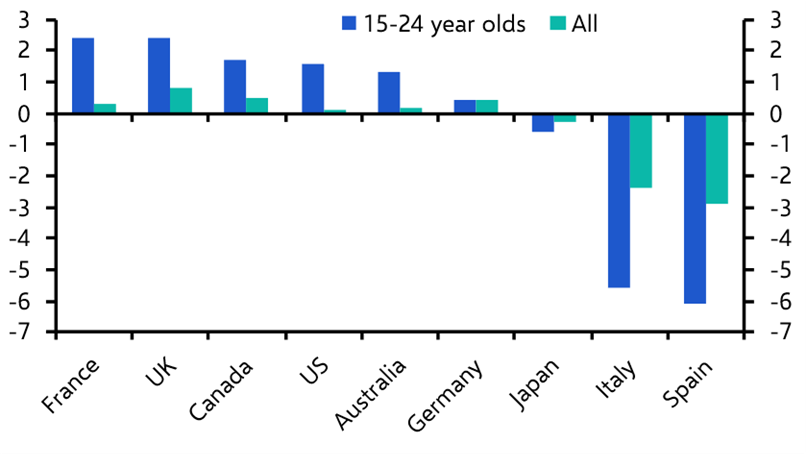

Vicky Redwood tackled the first issue in an in-depth report last week which offered a more sceptical take than much of the current commentary. There is no denying that labour markets have softened and that younger workers have been hit hardest. Youth unemployment has risen faster than for older cohorts, and listings for graduate and entry-level jobs have fallen sharply. (See Chart 1.) Some have been quick to attribute this to employers replacing junior staff with generative AI.

|

Chart 1: Unemployment Rate (% point change, Jan. 2022 – Jun. 2025) |

|

|

|

Sources: OECD, Capital Economics |

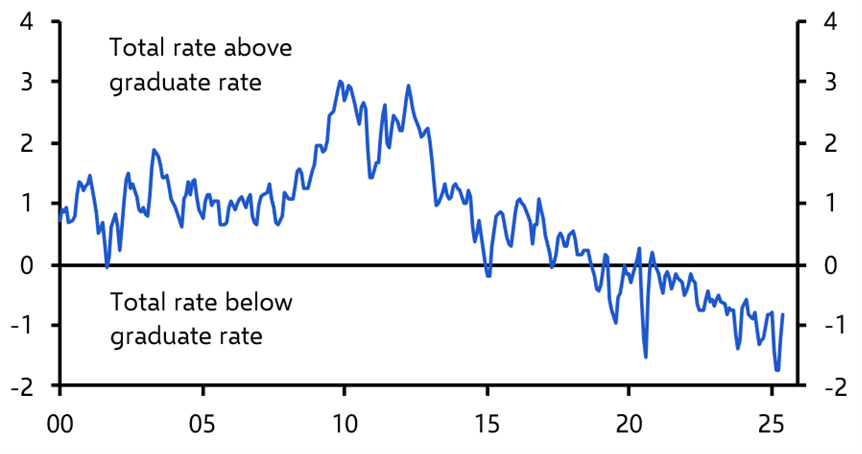

But that explanation looks too neat. For one thing, as Chart 1 shows, the biggest increases in youth unemployment have been in Canada and some countries in Europe, including France – economies that haven’t been at the forefront of the AI revolution. What’s more, many of these trends were already in motion before the AI boom began. In the US, the unemployment rate for graduates overtook the total unemployment rate in 2020 – more than two years before the launch of ChatGPT. (See Chart 2.) The sectoral data paint a mixed picture too: even in occupations most exposed to AI automation, such as IT, there is little consistent evidence of mass displacement of workers.

|

Chart 2: US Unemployment Rate: Total Minus Recent Graduates* (% points) |

|

|

|

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Capital Economics. *Graduates aged 22-27 years old. |

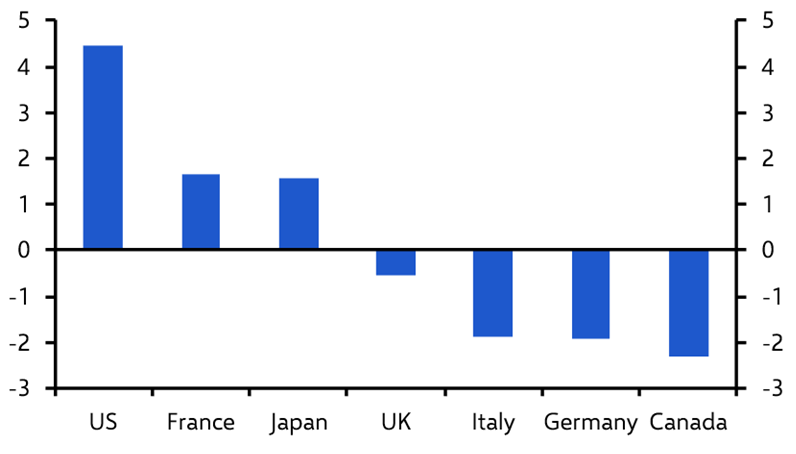

Productivity trends tell a similar story. If AI were already substituting for labour on a large scale, we would expect to see output per worker rising sharply. Productivity is hard to measure in real time and academic studies suggest that it can be underestimated in the early stages of technological revolutions. That said, the weakness of productivity in the developed world remains striking. With the important exception of the US, it has been flat or falling in most countries in recent years. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 13: Output Per Worker (% Change, Q1 2022 – Q2 2025) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

More plausibly, recent weakness in graduate hiring reflects cyclical and structural factors unrelated to AI. Labour markets have loosened more broadly, and inexperienced workers are typically the first casualties when firms slow hiring. Degree “inflation”, reflecting increasing graduation numbers and higher grades, has weakened the signalling value of degrees and intensified competition for entry-level roles. At the same time, parts of the tech sector are simply unwinding the over-hiring that followed the pandemic.

The upshot is that AI may be having some localised effects – particularly in certain programming and data-related roles – but its overall impact on employment is probably still small.

How to think about AI investment

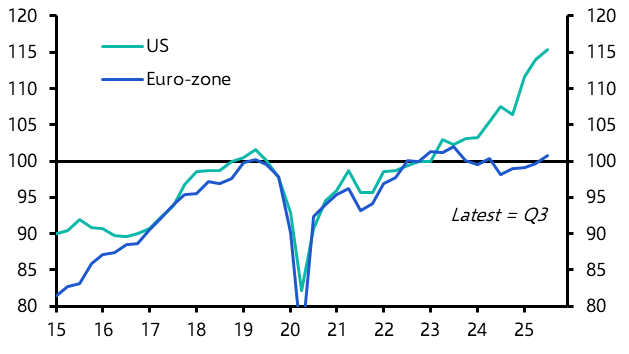

The second question relates to whether the huge capital spending programmes of the hyperscalers are justified and is more complicated. Much of the discussion here has been muddied by confusion between nominal and real investment. Firms think about their investment plans in nominal terms: the amounts they plan to spend versus the revenues they expect to earn back. Economists, however, think in real terms – that is to say, investment adjusted for changes in prices. This measures how much productive capacity is being added to an economy.

Concerns about the scale of AI investments have intensified following the enormous and growing capital-expenditure plans outlined in the third-quarter earnings reports of the so-called hyperscalers, the large tech firms at the epicentre of this technological revolution.

From a corporate perspective, what matters is whether the enormous sums being poured into data centres, chips and other parts of AI infrastructure generate a sufficient nominal return over time. The scale of current investment is comparable to past technological surges – from railways to the internet. As history shows, booms like these almost always involve some degree of overreach. Some projects will fail to pay back, leaving investors nursing losses.

But the implications for the real economy are more nuanced. The recent rise in US productivity has been helped by the rollout of AI, but the impact has probably been small and confined largely to early adopters in professional services. Instead, history suggests that the broader productivity payoff from general-purpose technologies arrives only once they are deployed at scale across the economy, and that this usually requires an initial phase of overinvestment to cut costs and build capacity. As prices fall, adoption widens, pushing up real investment even as nominal spending levels out.

This process inevitably creates some losers. But even if some companies that overinvest in capacity go bust they still leave behind some infrastructure that is ultimately valuable. (Think of the massive rollout of fibre optic networks during the dot-com boom.) In other words, what may look like wasteful investment from a financial standpoint – and indeed is a waste for some firms, with consequences for their investors – can be an important part of the economic diffusion process.

This means it’s possible to believe two things at once: that parts of the AI investment surge are excessive and will eventually correct and that the broader economic effects of AI could still be profoundly positive.

More debt, more danger

A separate but related concern is not the size of all this investment itself, but how it is being funded. If most is financed from free cash flow, the fallout from any correction would be contained. But the growing use of debt and special purpose vehicles to back AI projects is a risk worth watching. Excess leverage has a habit of turning sectoral bubbles into systemic problems, with spillovers to the real economy.

For now, overall leverage is low and those risks look manageable. But the bottom line is that while AI may be fuelling a bout of financial exuberance, it could also be laying the foundations for the next wave of productivity growth.

In that sense, we may be entering one of those rare periods where investors overreach – but the economy benefits all the same.

In case you missed it

What’s the state of the AI-led equities rally? Join us this Thursday for a post-Nvidia earnings Drop-In where we will unpack what recent market volatility tells us about the outlook. Registration details.

Will the AI narrative continue to grip markets in 2026? How will the US-China tech arms race shape the geo-economic outlook? Join our economists for our in-person global macro and markets outlook in London on 2nd December. Registration details.

The political noise ahead of the 26 November Budget has been intense, but how will Rachel Reeves’s choices actually feed through to growth, fiscal risks and market outcomes? If you missed our in-person sessions last week, join our UK team this Wednesday for an online Drop-In.

Amid another Sino-Japanese diplomatic row, Marcel Thieliant assessed the potential economic impact of a Chinese consumer backlash if Beijing’s relations with the new Takaichi government deteriorate further.