Three developments over the past fortnight have rekindled concerns about rising levels of government debt and the sustainability of public finances across advanced economies. First, France reported a larger-than-expected budget deficit of 5.5% of GDP for 2023 which meant its public debt ended the year at 111% of GDP. Then, on the other side of the Atlantic, Larry Fink of Blackrock and Ken Griffin of Citadel both separately voiced concerns about what Fink described as “snowballing” levels of US government debt. Finally, and perhaps most worryingly, the US Congressional Budget Office released updated projections showing that federal debt was on track to rise to a record high of 116% of GDP by the middle of the next decade. So how worried should we be about public debt risks in the world’s major economies?

A large and widespread fiscal expansion

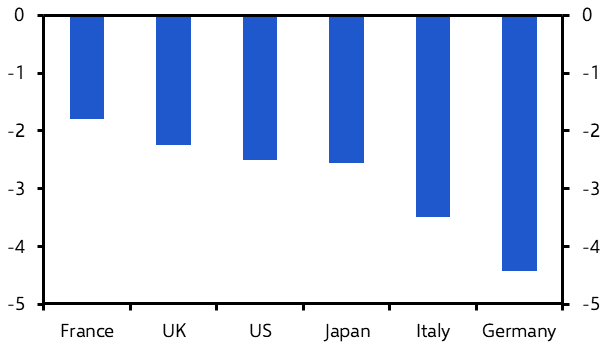

First the facts. There is little doubt that there has been a large and widespread loosening of fiscal policy across advanced economies compared to the pre-COVID period. Budget deficits have increased by between 1.8% (France) and 4.4% (Germany) of GDP since 2019. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Change in General Government Budget Balance 2019-2023 (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: IMF |

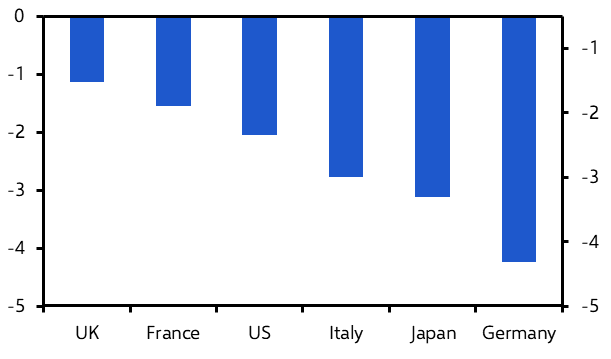

This partly reflects the effect of higher interest rates, which have pushed up government borrowing costs. But primary budget balances, which exclude expenditure on debt servicing, have also deteriorated by between 1.1% (UK) and 4.2% (Germany) of GDP over the same period. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: Change in General Government Primary Budget Balance 2019-2023 (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: IMF |

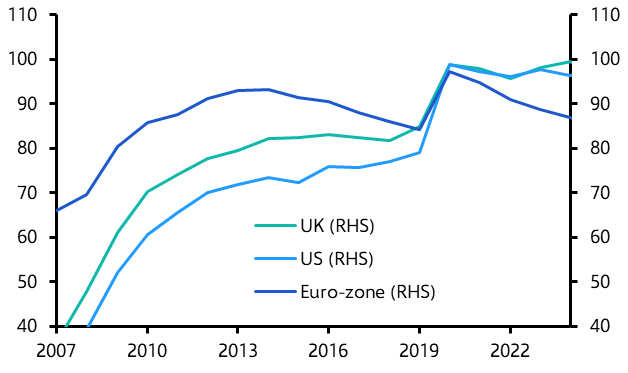

At the same time, public debt burdens have increased significantly. The ratio of government debt to GDP increased in all economies in 2020 because of the fiscal support provided during the pandemic but also because GDP collapsed. Since then debt ratios have either edged down (most countries in Europe) or stabilised (the US and UK), but they remain well above pre-pandemic levels. (See Chart 3.) What’s more, the trajectory of public debt has deteriorated because governments are running larger deficits than they were before the pandemic and interest rates on government debt have risen.

|

Chart 3: Net Government Debt (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: Capital Economics |

This is not all bad news. Fiscal support has been one reason why, despite a significant tightening of monetary policy, advanced economies have so far avoided deep recessions. However, there are justifiable concerns about whether the current fiscal trajectory is sustainable.

Working through the fiscal arithmetic

The path of public debt/GDP is governed by a combination of the primary budget balance, interest rates and (nominal) GDP growth. In particular, if interest rates rise above the rate of nominal GDP growth, then governments must run a primary budget surplus in order to keep the public debt ratio stable. Conversely, if the rate of nominal GDP growth exceeds interest rates then governments can run primary deficits and continue to keep the public debt ratio stable.

The medium-term outlook for growth may not be as bad as many now seem to assume. We remain optimistic that the AI revolution will deliver a meaningful improvement in productivity growth towards the end of this decade, particularly in the US. Our analysis suggests that under plausible assumptions this could boost government revenues in the US by 1.0-1.5% of GDP a year.

However, the fiscal boost in other countries (notably in Europe) will be smaller. And even in the US there is huge uncertainty as to when any AI-related fiscal dividend might arrive. It would therefore be unwise for governments to set fiscal policy on the basis that they will be bailed out by an AI-related boost to revenues. This is all the more the case given that long-term pressure on the public finances from other sources including ageing populations and the costs of the net zero transition looks set to intensify.

The upshot is that governments across the developed world will need to undertake fiscal consolidation in order to stabilise public debt positions. This need not be a major drag on growth if it is managed in a gradual way and comes alongside a strengthening of private sector demand. The key question, then, is whether governments are given the time and space by markets to narrow deficits in a controlled manner, or whether a loss of investor confidence and a bond market backlash forces them into a more aggressive and immediate adjustment.

A confidence game

This is where perceptions become critically important. Most fiscal crises over the past five years or so have been caused by a belief within markets that the government in question has lost – or is losing – fiscal credibility. This has not always been the result of a change in actual policy, so much as a belief that their commitment to fiscal rectitude had waned. The crisis that followed in the wake of Liz Truss's disastrous “Mini-Budget” in the UK in 2022 is a good example. Accordingly, maintaining fiscal stability becomes a confidence game. The trick for governments is to persuade bond markets of their commitment to fiscal responsibility, while at the same time reducing budget deficits in a measured and gradual way. The interplay between bond market confidence and government borrowing costs is one reason why estimates of the size of the necessary fiscal consolidation are not particularly helpful – a large part of the answer depends on what happens to bond yields.

Will governments win this game of confidence? In the US and UK, the biggest risk is perhaps that governments – or prospective governments – rattle bond markets with talk of unfunded tax cuts or spending promises ahead of elections later this year. There has so far been remarkably little talk of fiscal giveaways in either country, which is perhaps a tacit acknowledgement by politicians in both countries of underlying public debt vulnerabilities. It remains to be seen whether this can hold through to election days.

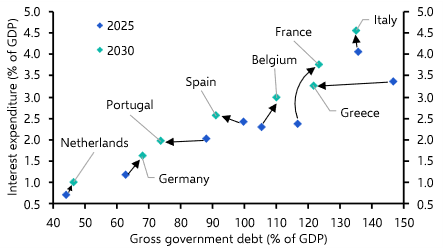

Elsewhere, some of the biggest risks lie in countries where interest rates have been pulled up by global or regional factors without a corresponding increase in growth. Italy continues to be a cause for concern in this regard. It has flown under the radar in recent years, thanks in part to the Meloni government adopting a more conciliatory approach to the EU than some previously Italian governments. However, in practice Italy ran a much larger than expected deficit last year, of 7.2% of GDP, due in large part to an expensive tax subsidy for residential construction. Moreover, Italy’s long term debt dynamics are grim and the country operates within the straitjacket of monetary union. It would be remarkable if it managed to stay out of the firing line forever.

In case you missed it:

- Simon MacAdam calls time on the debate over “excess savings”.

- Andrew Kenningham argues that economic weakness in Germany’s is part cyclical and part structural.

- Our markets team navigate asset allocation in an era on an AI bubbles.