The outcome of ‘Super Tuesday’ all but confirmed a Biden-Trump rematch this November. The Republican candidate’s protectionist threats are one reason why his re-election is seen as the greater global macro risk. But significant – and underappreciated – structural changes in China’s economy mean that Washington and Beijing are on a collision course over trade regardless of who wins.

This was a key theme of client meetings in the US and Asia over the past fortnight. The key point, that has been largely missed in the debate, is that this election is taking place against the backdrop of a substantial rebound in China’s external surplus.

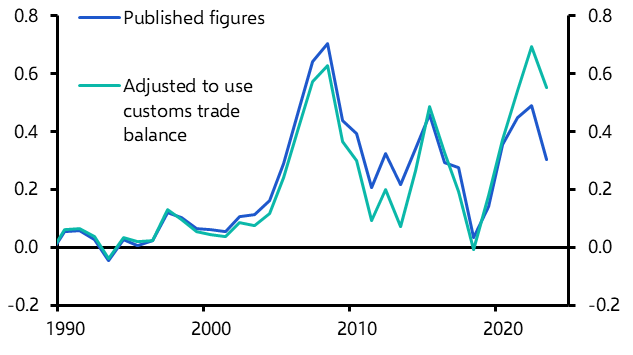

This isn’t seen in the official balance of payments data, which show that China’s current account surplus has increased as a share of global GDP in recent years, but remains some way below its late-2000s peak. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: China Current Account Balance (% of World ex-China GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: State Administration of Foreign Exchange, Capital Economics |

However, China's customs data paint a very different picture. They show the current account surplus close to a record high as a share of global GDP. The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear, but the most convincing explanation is that the customs data do a better job of reflecting the growing use of bonded warehouses and offshore trade zones in shipping Chinese exports. As a result, we suspect they paint a more accurate picture of the reality on the ground.

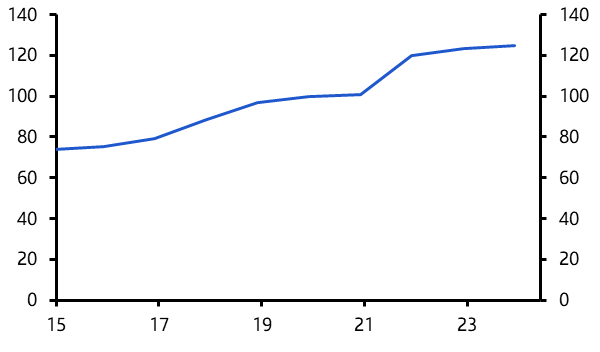

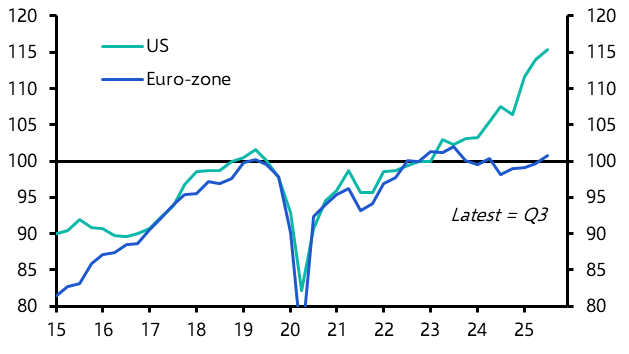

The rebound in China’s external surplus has been underpinned by a substantial expansion of its manufacturing capacity during the pandemic. (See Chart 2.) Although the world under lockdown fuelled talk about global goods supply shortages, Chinese (and thus global) goods supply increased substantially between 2020 and 2023. Instead, supply bottlenecks and price increases were caused by an even greater increase in demand.

|

Chart 2: China Manufacturing Output (2019=100) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Although that demand has since normalised, the expansion of Chinese supply remains in place. Some of this was intended to meet increased pandemic-era demand and some – such as electric vehicles – represents deliberate, long-term policy decisions made in Beijing. Either way, the outcome is Chinese manufacturing output that is now more than 25% higher than at the end of 2019.

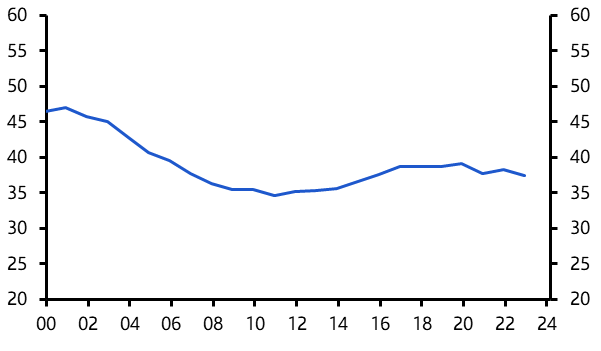

This additional supply needs to find a home, but China’s consumer demand remains structurally weak. Household consumption accounts for just under 40% of GDP compared with nearly 70% in the US, and this share has not materially changed in recent years, despite policy commitments to boost it. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: China Household Consumption as % GDP |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

It follows that increased Chinese supply is being met by foreign demand, and that has driven the rebound in China’s current account surplus. In the Premier’s work report delivered to the National People’s Congress last week, Li Qiang pledged to expand domestic demand this year. But he gave as much time to the importance of boosting investment demand as he did to consumption, signalling that this imbalance between supply capacity and what can be absorbed domestically is not going away.

All of this has two consequences – one that’s broadly positive, and another that’s altogether more troubling.

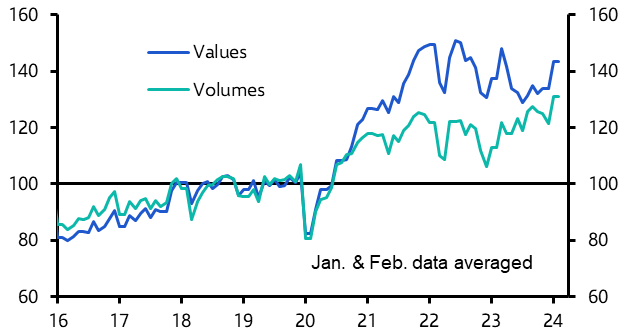

The positive result is that the expansion of Chinese supply has helped to bear down on global goods inflation. Although China’s exports are running at a record high in volume terms, they are lower than a couple of years ago in value terms – indicating that exporters have had to cut prices in order to sell their products. (See Chart 4.) While this has played only a supporting role in the overall decline in inflation in advanced economies over the past year, it has been helpful at the margins for central banks. (See here.)

|

Chart 4: China Exports (USD, (2019 = 100), seas. adj.) |

|

|

| Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

The more troubling consequence relates to the political and geo-economic fallout from the rebound in China’s external surplus. Beijing’s efforts to reform the global trading system to its benefit are starting to gain more attention. These include trade agreements providing tariff-free access for Chinese exporters while at the same time facilitating investment flows from China to the participating country. Beijing has so far agreed 28 such deals, with others, including with Gulf economies, seemingly close.

However, China is hamstrung by its size. It now accounts for nearly 15% of global manufacturing exports. The countries with which it has agreed free trade deals are relatively small and therefore lack the internal demand required to absorb Chinese output. In contrast, the US remains the world’s largest consumer market. Taking into account Chinese trade flows that have been rerouted via third countries, China’s exporters are probably more reliant now on US consumers than they were when the trade war began during Donald Trump’s first term.

This significantly reduces Beijing’s ability to reshape the global trading system to China’s benefit. More importantly, it also means that China will remain dependent on US – and European – demand for its exports for years to come. The end result will be a persistent increase in the US’s bilateral trade deficit with China.

One of the very few bipartisan issues left in Washington is the imbalanced nature of the US trading relationship with China. Investors may be nervous about the potential return of Mr Trump and the threat of a renewed trade war, but that conflict looks ever more likely whether the next administration is Democrat or Republican.

In case you missed it

Our dedicated US elections page has all the key analysis about the macro and market implications of November’s vote. This election is being fought as the global economy fractures into US and China-aligned blocs. Learn more about that process, and its implications, on this Key Issues page.

Deputy Chief US Economist Andrew Hunter showed what Jerome Powell’s congressional testimony and the recent US data haul means for the outlook for the first Fed rate cut.

Our Japan team explained why the data and mood music from Tokyo suggest the BOJ could move to end negative rates at this month’s meeting on 19th March, rather than in April as forecast.

And don’t miss our UK pre-election online briefing this Wednesday at 1100 EDT/1500 GMT.