Over the past year the global economy has been buffeted on several fronts: from escalating trade tariffs to assaults on policy norms and longstanding institutions, and now warnings of a fracture in the global order. Yet, for all this noise, global economic activity has remained remarkably resilient. The obvious questions are: why has this happened? And can it last?

Let’s start with the data. Our latest GDP nowcast suggests that the US economy grew at a pace of close to 4% q/q annualised in the final quarter of last year, following growth of 4.4% q/q annualised in the third quarter. Momentum has carried into the start of this year. Business surveys have strengthened, with the ISM manufacturing index rising to a three-year high in January. A solid reading in the ISM services index means our composite ISM balance is now at a 15-month high.

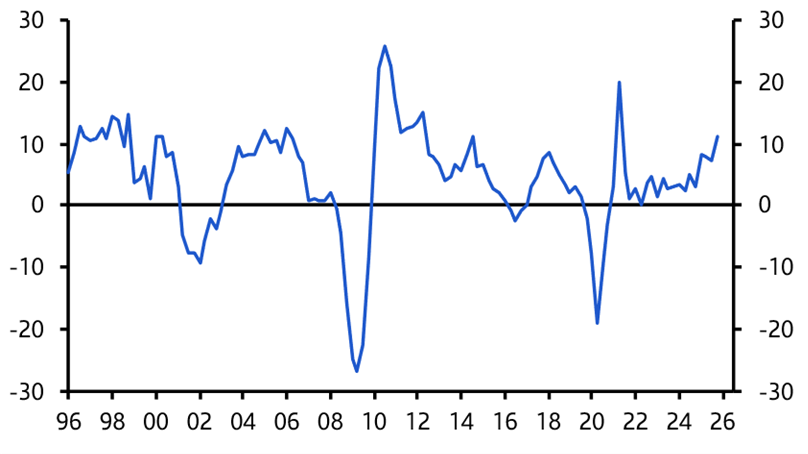

Crucially, business investment has stayed remarkably robust, driven by continued spending on AI, energy and infrastructure. This matters because if policy uncertainty were truly weighing on economic activity, business investment would be the first place it would show up. For now, it is not. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Business Equipment Investment (% y/y) |

|

|

|

Sources: BEA, Capital Economics |

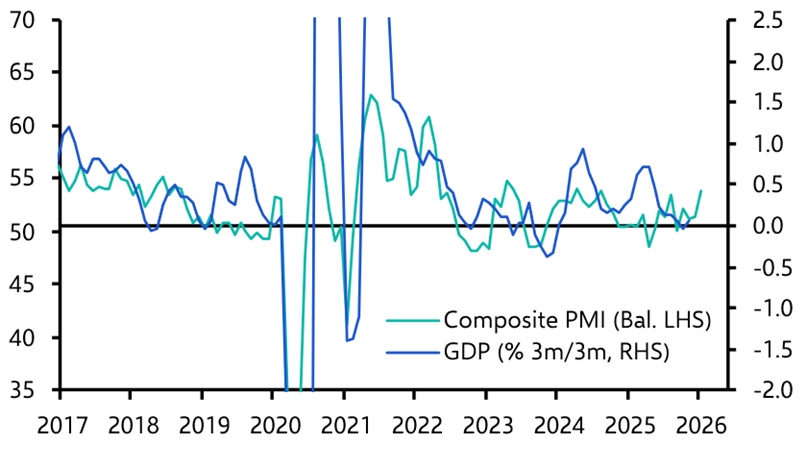

Across the Atlantic, growth is undeniably weaker, but even here the picture is not uniformly bleak. The euro-zone economy (excluding Ireland) expanded by 0.4% q/q in the fourth quarter of last year, which by the standards of recent years is respectable. Fiscal easing in Germany is unlikely to deliver a dramatic uplift in growth under even optimistic assumptions, but it should provide some support. Some economies, notably Spain, are performing much better. Overall, euro-zone growth of around 1% this year looks plausible. Meanwhile, the latest data suggest that economic activity in the UK has strengthened since the start of the year. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: UK Composite PMI & Real GDP |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG Data and Analytics, S&P Global, Capital Economics |

Explaining resilience

So what explains the resilience of the global economy? Part of the answer is that, for all the heated rhetoric, there has been little substantive change in policies that materially affect the real economy. The guardrails around key economic institutions appear to be holding. The big threat hanging over the US economy and markets – that Fed independence could be significantly compromised – has faded in the wake of the nomination of Kevin Warsh to be the next Fed Chair.

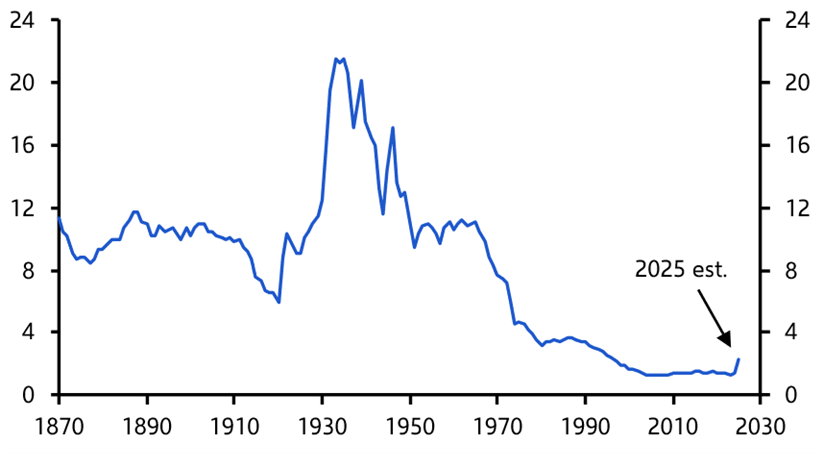

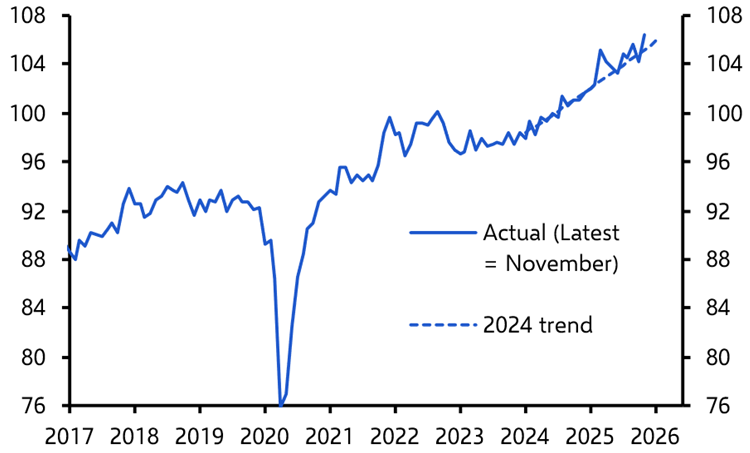

Meanwhile, for all the talk of trade wars, the effective global tariff rate remains low. (See Chart 3.) And while US tariffs have risen, supply chains have adapted. The result is that global trade remains at record highs. (See Chart 4.)

|

Chart 3: Global Effective Tariff Rate (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: Lampe & Sharp (2013), Federico-Tena (2019), Jacob Madsen, UN Statistical Yearbooks, Comtrade, IMF, World Bank, Capital Economics |

|

Chart 4: Real World Goods Trade (2024 = 100) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG Data and Analytics, Capital Economics |

A broader truth

This points to a broader truth: governments tend to have less influence over short-term economic outcomes than the political debate often suggests. Economies are complex, adaptive systems and, in the absence of a large shock, typically evolve only slowly and with considerable inertia. Governments can, of course, do serious damage by pursuing reckless fiscal or financial policies – as the UK briefly demonstrated during the government of Liz Truss in 2022 – but beyond that their ability to influence quarter-to-quarter growth is more limited than is commonly believed.

What’s more, none of this is happening in isolation. With fiscal policy broadly supportive, unemployment low, inflation easing (particularly in Europe), and a powerful AI-driven investment cycle underway in the US, it would be surprising not to see decent growth numbers.

China’s structural problems

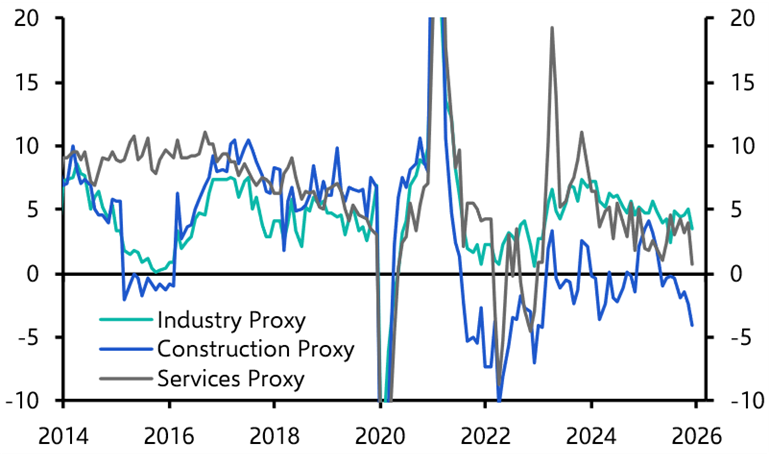

The main fly in the ointment is China. Admittedly, the labour market data are showing some signs of improvement. But structural headwinds persist. Our China Activity Proxy points to growth of under 3% y/y in Q4. Construction appears to have contracted by around 2.5% y/y, reflecting the continuing downturn in the property sector. Meanwhile, services and manufacturing expanded by around 2.5% y/y and 4.5% y/y respectively. (See Chart 5.)

|

Chart 5: CE China Activity Proxy (Sector Breakdown, % y/y) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG Data and Analytics, Capital Economics |

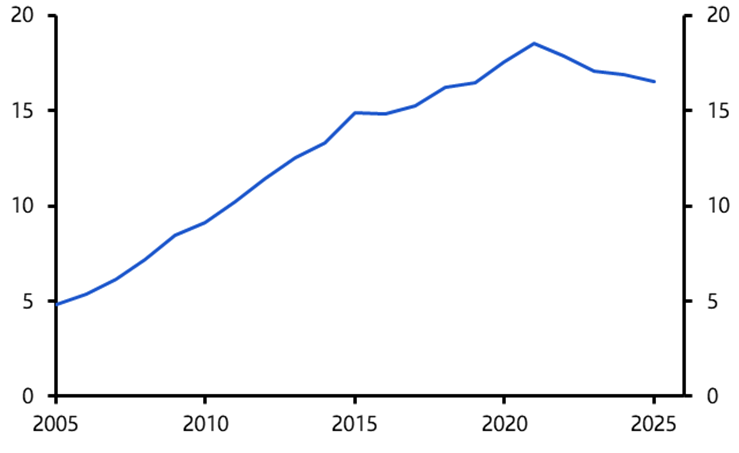

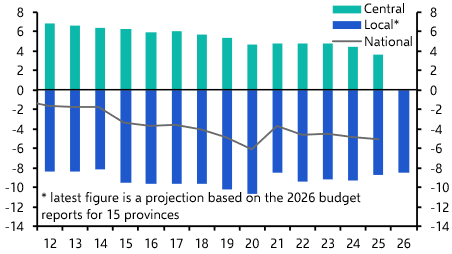

Crucially, these figures are in volume terms. Manufacturing output is being sustained largely because firms are cutting prices and shipping production to foreign markets. This reflects the ongoing weakness of domestic demand relative to supply. Export prices have fallen by around 25% since 2022, creating a deflationary environment at home and meaning that China’s share of global GDP is now falling in nominal terms. (See Chart 6.)

|

Chart 6: China’s share of global GDP (%, market exchange rates) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG Data and Analytics, S&P Global, Capital Economics |

Global imbalances build

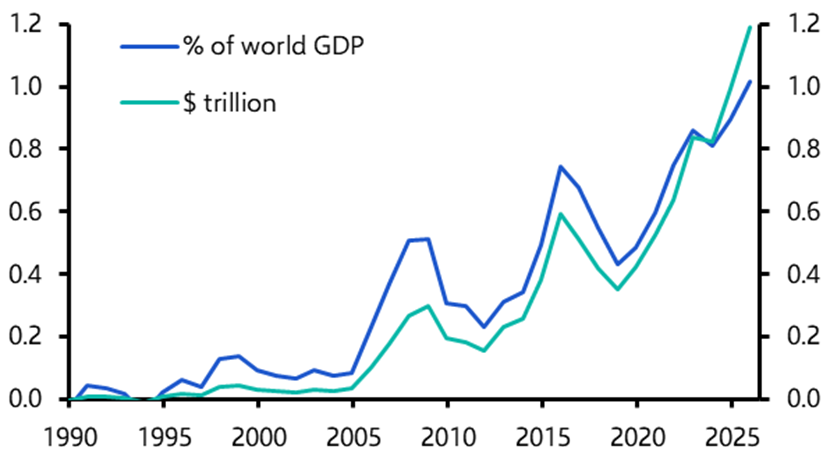

The flip side is a trade surplus that has risen to a record share of global GDP. (See Chart 7.) This, too, should not be surprising. The deficits that are sustaining aggregate demand in the US must, by definition, be matched by surpluses elsewhere.

|

Chart 7: China’s Trade Surplus |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG Data and Analytics, Capital Economics |

Some degree of imbalance is normal; the goal is not perfectly balanced trade, but sustainability. The problem is that China’s large surplus requires that other countries accumulate large amounts of external liabilities, while at the same time accepting that domestic producers will be continually squeezed by their Chinese counterparts. For now, these imbalances do not seem to have reached a point where they pose an immediate threat to the global outlook. The borrowing in deficit countries is being done primarily by the public rather than the private sector and, for the time being, sovereign bond markets do not seem unduly concerned. If economic growth falters in the near term, more likely triggers would be a sharper-than-expected slowdown in US hiring that becomes self-reinforcing, or a sudden halt to the AI investment boom. Our base case remains that the global economy continues to hold up through 2026.

But over the longer run, the accumulation of global imbalances – and China’s surplus in particular - looks unsustainable. At some point, an adjustment will be unavoidable. The near-term outlook for the global economy remains pretty good but a reckoning will ultimately come – the only uncertainty is how painful it will be.

Related content

- Marcel Theiliant gives a first take on PM Takaichi’s sweeping election victory in Japan.

- Our Global Economics team argues that inflation will undershoot consensus expectations in 2026-27.

- Shilan Shah unpacks the economic and geopolitical ramifications of the US-India trade deal.