It’s big, but it’s far from beautiful. In fact, the sheer size of the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill Act’ that’s currently working its way through Congress is part of what makes it so unwieldy – and so unattractive.

Size matters

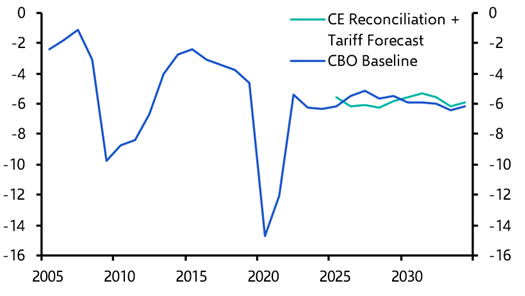

As we’ll argue in a report coming this week, the tax bill in its current form includes cuts that would mean the US runs a federal budget deficit of 6-7% of GDP over the next few years, depending on how much revenue is raised through Donald Trump’s tariffs. (See Chart 1.) This would keep the US public finances on an unsustainable trajectory.

|

Chart 1: Federal Budget Balance (% of GDP)

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

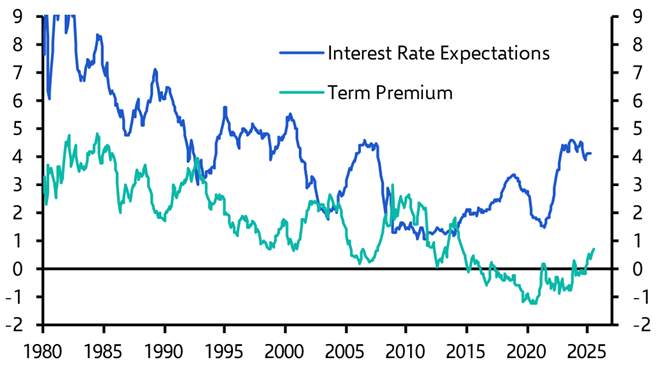

The US is not staring down the barrel of the kind of debt crisis that gripped the euro-zone just over a decade ago. But sustained large deficits, a high and rising debt burden and a relatively low domestic savings rate will leave the US Treasury market vulnerable to periodic bouts of investor unease. The term premium component of the nominal 10-year Treasury yield – a measure of that unease – remains low, but is on a clear upward trajectory. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: Breakdown of 10-Year Treasury Yield (%)

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

Section 899 ≠ capital controls

But it’s not just the size of the bill’s tax cuts that has investors nervous. Buried deep inside its pages is section 899. This outlines how the US government could impose taxes on individuals, businesses and other entities from countries deemed to have a tax regime that discriminates against US interests. This would include countries that levy a digital services tax, meaning it could potentially affect those from the UK, France, Germany, Canada, Australia and India.

This isn’t without precedent. Section 891 of the tax code has lain on the books since the Great Depression – when US protectionism was last at a peak – and authorises the doubling of taxes on citizens and firms from countries whose tax policies are deemed discriminatory toward the US.

Even so, this is a febrile environment for dollar assets and the attention on section 899 has only fuelled market anxiety, with commentators labeling it variously as a “ticking time bomb” and a “revenge tax.” Some have even criticised the proposal as signalling the early stages of the US imposition of capital controls.

That’s a criticism too far. Capital controls are designed to restrict the flow of capital in and out of a country. In contrast, section 899 is aimed at the tax policies of countries that are perceived to act against US interests. They are not intended to reduce capital flows in or out of the US. What’s more, we suspect that the market implications of section 899 may ultimately be more limited than many now seem to fear.

How would capital controls work?

With that said, it is no longer impossible to imagine that the US might consider imposing some form of control on capital flows in an effort to rein in its large trade and current account deficits. Indeed, earlier this year American Compass, a think tank close to Vice President JD Vance, advocated for the introduction of capital controls in the form of a “market access charge”. While it estimated that this could raise up to $2trn in federal government revenues over the next decade, importantly, the case for restrictions on capital controls was framed in terms of helping to reduce America’s trade deficit. Stephan Miran, who is now Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors, has previously floated the idea of a “user fee” levied on holders of US Treasuries.

The key point here is that the balance of payments must, by definition, balance. If capital inflows to the US are reduced then its current account deficit must fall by an equivalent amount. Put differently, if foreigners become less willing to finance the US current account deficit then the deficit itself must shrink. Accordingly, if the Trump administration really is intent on narrowing America's trade and current account deficits then restricting inflows of foreign capital would be one way to achieve this.

However, this would not be a cost-free adjustment. For one thing, the mere threat of these controls could wreak havoc in financial markets. One component of the success of US financial markets has been the relatively frictionless access to them. A whiff that capital controls are coming and investors could quickly take flight. More generally, the economic consequences of capital controls would depend to a large extent on the channels through which they were allowed to operate. Any reduction in foreign demand for US assets should, all other things being equal, push up US borrowing costs. This in turn would squeeze domestic demand in the US, causing demand for imports to fall and the current account deficit to narrow. But the reduction in domestic demand would also threaten to push up unemployment.

The Federal Reserve could of course counter any rise in borrowing costs by lowering interest rates. In this case, the main channel through which capital controls would operate would be through a weaker dollar. This is the tried and tested route for balance of payments adjustments. A weaker dollar should in theory simultaneously squeeze imports and boost the competitiveness of US exporters. Because currency shifts affect both the import and the export side of the trade balance they are generally viewed by economists as the best way to narrow deficits (as opposed to tariffs, which affect only imports). The imposition of capital controls could be one way to force a weaker currency.

However, rebalancing through a weaker dollar would still require US firms to be able to produce the goods that are currently made overseas. In many cases, it would take time for imports to be substituted for domestic production. More fundamentally, the US economy is already operating at full employment. Even in the event of a surge in export demand, or widespread import substitution, there is limited capacity to raise domestic production.

The heart of the problem

This gets to the heart of the problem, which is one of US over-consumption. The counterpart to this is under-consumption in surplus countries, the most important of which is China, though Germany, Japan and Taiwan are also on the list. The most effective way to remedy these imbalances would be fiscal retrenchment in the US alongside an expansion of demand in China and other surplus countries. This would be the best hope of keeping all economies at full employment while at the same time narrowing global trade imbalances.

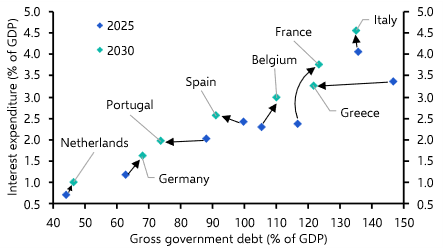

However, there is little prospect of this happening any time soon. For all the talk of stimulus in China, fiscal expansion is failing to give much of a lift to domestic consumption. Likewise, Germany’s fiscal reforms will increase its budget deficit (and reduce its current account surplus) by only around 1% of GDP. To put this into context Germany’s current account surplus is currently running at just over 5% of GDP. Meanwhile, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act points to the US continuing to run large budget deficits.

For as long as this remains the case, the most likely scenario is that global imbalances remain stubbornly large. And for as long as the US runs vast deficits in an increasingly unilateralist geopolitical climate, once-marginal ideas like capital controls will keep creeping toward the mainstream of policy debate.

In case you missed it:

The same Chinese economy that sits at the cutting edge of technology is in the midst of a productivity growth slump. Chief Asia Economist Mark Williams explains what’s gone wrong.

The ONS’s admission that it overstated April’s CPI is the latest sign of the UK’s data quality problems – and lends weight to Deputy Chief UK Economist Ruth Gregory’s recent warning that flaws may run more widely through official statistics.

The recent run of Indian equities outperformance is unlikely to continue in the near-term, says Markets Economist Shivaan Tandon. He’ll be outlining our non-consensus views on India’s markets in a Drop-In on Tuesday (register here).