Fiscal policy returns to centre stage this week, with Chancellor Rachel Reeves set to deliver her Autumn Budget on Wednesday.

The debate will revolve around the size of the fiscal squeeze required to hit the government’s self-imposed rules and, crucially, the mix of tax rises and spending restraint used to achieve it. We think she will need to find something in the region of £35-40bn. Most of this is likely to come via higher taxes. But much ultimately hinges on the Office for Budget Responsibility, the government’s fiscal watchdog, and what it decides to assume about future productivity growth. A generous OBR could make the arithmetic look far less painful; a cautious one could force a bigger squeeze (our UK Budget page has the latest on the budget’s implications. You can also register for our online Drop-In briefing shortly afterwards.)

Either way, the political reaction will matter as much as the numbers. The key question is how this lands with the parliamentary party and whether it stirs further manoeuvring against the Prime Minister and the Chancellor. A change in leadership would almost certainly push the party leftwards and produce a government with weaker fiscal credentials – an outcome that would hardly reassure the gilt market.

The UK is not alone – or even the worst offender

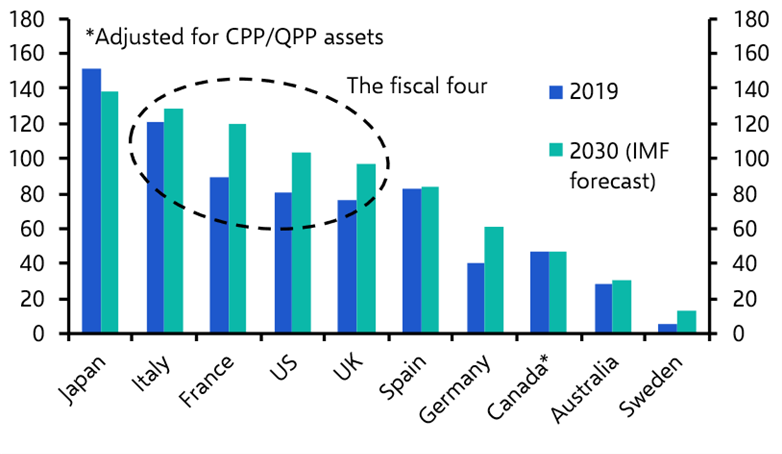

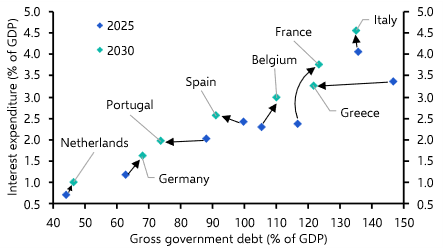

The UK, of course, is not alone in having fiscal challenges. Across the advanced world, public debt ratios are uncomfortably high and budget deficits wide. The worst offenders are the US, France and the UK. (See Chart 1.) Italy’s debt burden remains enormous, but Rome at least is running a smaller deficit. Indeed, the UK is somewhat unusual in having a government that is at least attempting to stabilise the public finances. Italy, too, has shown a surprising degree of restraint. France, by contrast, has chewed through four governments without making much progress. And in the US, politicians in both parties seem determined to ignore the long-term fiscal challenge altogether. By this standard, the UK starts to look like a paragon of virtue.

|

Chart 1: General Government Net Debt (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

What unites all of these countries are fiscal problems that are emerging at or near full employment. That matters because there is no cyclical upswing waiting in the wings to repair the public finances for them. Without a cyclical recovery in tax revenues, governments need either a structural fiscal tightening or a concerted effort to raise their economy’s potential (or trend) rate of growth – and in practice, probably both.

A problem of growth

This is where the real problem lies. Across advanced economies, there is no coherent, fully-fleshed out strategy for lifting long-term growth. Where plans exist, they either rest on wishful thinking – see the Trump administration’s mix of tax cuts, deregulation and protectionism – or amount to a general declaration of good intentions, heavy on aspiration but light on the politically difficult trade-offs required to make them stick.

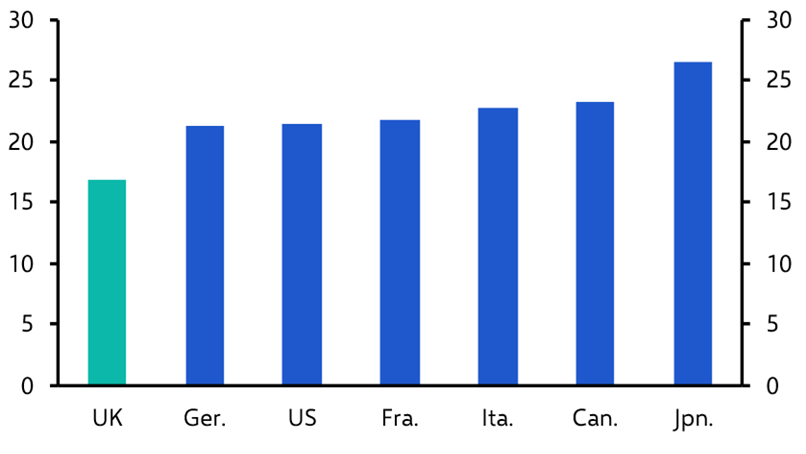

The UK falls into this latter category. To the extent that the government has a growth plan, it is built around raising investment. This is sensible enough: the UK has the lowest investment rate in the G7 and a chronically weak capital stock. (See Chart 2.) But ministers have ignored the uncomfortable truth that in an economy already operating at full capacity, higher investment requires someone, somewhere, to consume less. Either private households or the state – and more likely both – will need to tighten their belts. That is how the additional savings needed to finance higher investment are created. Borrowing from overseas would simply bloat an already large current account deficit and is not a sustainable alternative.

|

Chart 2: Gross Capital Formation (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

The reality is that there is no single lever that boosts long-term growth. It requires a comprehensive plan pulling together macroeconomic adjustments – notably higher savings and investment – with reforms to infrastructure, skills, technology, planning, regulation, housing, trade policy, migration, and the labour market and welfare system. Even if governments get all of this right – and few ever do – the benefits will take years to materialise and may yet be derailed by events.

Waiting on manna from heaven

But the difficulty of the task is no excuse for not having a strategy. Without one, governments are left hoping that growth will descend, in Robert Solow’s memorable phrase, like “manna from heaven”. I remain optimistic that artificial intelligence will eventually deliver such a windfall. But that is unlikely before the end of the decade, and for now Europe and the UK lag well behind the US in adopting and diffusing the technology.

Absent a sustained rise in growth, fiscal pressures will remain a defining feature of the global economy over the coming year. My note next week will set out the themes we expect to dominate 2026. We’ll discuss them in full at our in-person event in London next Thursday 2nd December. Register here to join that event.

In case you missed it

- For more analysis of the economic implications of the peace deal that the White House is pressuring Ukraine to sign, see our latest Emerging Europe Weekly.

- With equity market sentiment remaining fragile amid worries about the sustainability of AI investment, Chief Markets Economist John Higgins weighed the risks of the bubble bursting any time soon.

- Chief Europe Economist Andrew Kenningham shows how the shift towards moderation by France’s far-right National Rally has eased investor fears, but also how it is no more likely than other parties to repair the country’s public finances.