The year’s home stretch is a natural moment to take stock of the major developments of the last twelve months and get some perspective on the likely challenges in 2026. With that in mind – and for those looking for a reading break from any holiday bustle – here’s a small list outlining the big themes that captured 2025.

1. Tariffs haven’t torpedoed trade

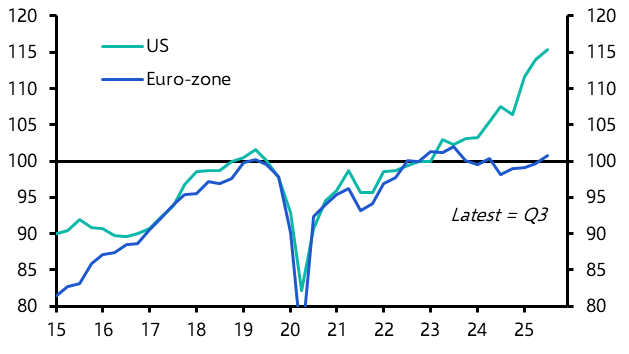

The first half of the year was dominated by debate over the impact of Donald Trump’s tariffs on the global trading system. As we suspected would be the case, the more apocalyptic fears have proven overdone. Global trade volumes have held up reasonably well and, while US-China trade has indeed collapsed, the US current account deficit is likely to end the year broadly unchanged from 2024. At the same time, China’s year-to-date trade surplus has already exceeded $1 trillion, the first time it has crossed this threshold. The broader lesson is that tariffs can reshape bilateral trade flows, but aggregate trade balances are governed by deeper structural forces, most importantly, the relationship between savings and investment. We see little prospect of a meaningful narrowing in global imbalances next year. And, as we explained in this note (and I argued in my book The Fractured Age), a deepening superpower rivalry between the US and China is likely to remain the key fissure in the global economy over the coming decade. How this rivalry evolves will play a much bigger role than Trump’s tariffs in determining its longer-term outlook.

2. AI rewiring the economy – and prompting big questions

If trade dominated the first half of the year, artificial intelligence was the dominant theme of the second. We have argued for some time that AI should be viewed as a general-purpose technology – akin to electrification or computing – and so capable of materially lifting productivity growth. In a major report in 2023, we concluded that the widespread adoption of AI could add as much as 1.5%-pts to annual productivity growth over the coming decade. As Paul Ashworth, our Chief North America Economist, has noted, there is now some evidence of these effects in the US data. We expect this process to continue through 2026.

This raises a host of important questions, most obviously whether the vast sums being poured into AI will ultimately pay off. Jennifer McKeown and John Higgins have shown the need to distinguish carefully between the implications for the real economy and those for financial markets. Follow-up notes explored the fall-out for equities when the AI bubble bursts and how central bankers can best mitigate investor exuberance. And as concerns grow around AI’s impact on jobs markets. Vicky Redwood showed why claims that the technology is behind the recent rise in youth unemployment don’t stand up to scrutiny.

3. China: Tech winner, structural loser

Most advanced economies have struggled to keep pace with the US in the AI race, but 2025 has also been the year in which China has closed part of the gap. This reflects the broader success China has had in competing with the US at the technological frontier. But as Mark Williams explains, this has not translated into an economy-wide acceleration in productivity. Indeed, the way in which China has pursued technological leadership is in some respects exacerbating deeper structural weaknesses, which continue to weigh on its broader growth prospects. The result is an economy that can produce national champions capable of rivaling America’s best-in-class tech firms, but not the rapid GDP growth of earlier decades. The next Five-Year Plan, due to be published in March, is an opportunity for reform but, as we explain here, we don’t expect a major shift in direction.

We’ll have much more to say on these themes – and on the many questions that 2026 will bring – over the year ahead. In the meantime, have a very happy holiday.

Neil Shearing, Group Chief Economist