- Inflation persistence has strengthened the drive for higher rates…

- … while weak exchange rates and fiscal policy concerns add to challenges for some.

- Peaks will be higher than we had assumed and the risk of policy mistakes has grown.

Recent developments have made a bad situation worse for central banks and what was already a challenging environment has become even more challenging. Not only is inflation proving more persistent than they had hoped, but several have had to contend with currency weakness and fiscal policy complications at the same time. All of this has increased the threat that inflation will rise out of control and endanger their credibility. The result is likely to be that interest rates rise even further than we had assumed and there is a growing risk that policy tightening will prompt deep recessions.

Stubborn inflation

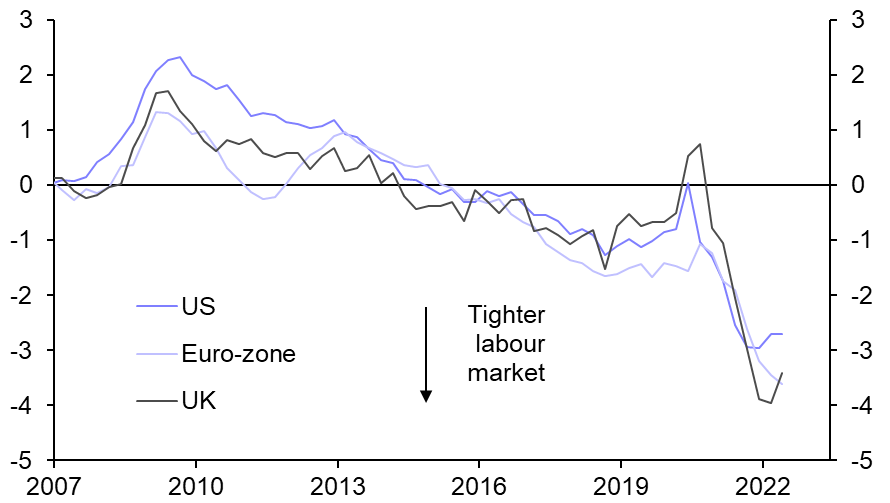

The familiar problem is that inflation continues to be more persistent than most had assumed. US consumer prices rose on the month in August rather than falling as expected, keeping headline inflation elevated at 8.3%. Meanwhile, euro-zone inflation rose to a record high of 10.0%. In both cases, and in the UK, core inflation increased again. What’s more, there is little respite in labour markets, where rates of unemployment are still very low and our indicators suggest that shortages remain acute. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: CE Labour Market Slack Indicators (Z-Scores) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

As we explained in detail in our latest Global Inflation Watch, there are signs of improvement in the US at least. Product shortages there have receded dramatically and a slowdown in consumer services producer price inflation indicates that underlying pipeline price pressures are easing. But those glimmers of light at the end of the tunnel are not as visible in other advanced economies.

What’s more, it will take more than an improvement in leading indicators to cause central banks to change their stance. The pandemic has caused so much uncertainty about supply potential that normal relationships cannot be relied upon to guide inflation forecasts. And with core inflation, wage growth and inflation expectations already out of line with central banks’ targets, their credibility is in danger. Back in 2015, economist Lawrence Summers argued that central banks should not raise interest rates until they had seen “the whites of inflation’s eyes” given a series of false dawns in preceding years. Now, the opposite is true and it will probably take a sustained decline in actual core inflation to convince central banks to take their feet off the brakes.

Weak currencies adding to price pressures

Meanwhile, exchange rate movements have worsened the policy challenge. The dollar’s strength increases the threat of recession in the US, which might, in time, give the Fed pause for thought. But in pretty much every other advanced economy, depreciations against the dollar are adding to already intense price pressures. And, in some cases, they raise more nebulous concerns about central banks’ credibility due to their perceived role as custodians of their currencies.

The clearest example of this challenge has been in Japan, where the Bank of Japan’s commitment to low interest rates has widened expected rate differentials and put particular pressure on the yen. The slide through 145 per dollar was enough to prompt the Bank to intervene in support of the currency by selling FX reserves. (See here.)

It is possible that other central banks will follow suit, but that doesn’t seem like the most likely scenario for three reasons. First, currency intervention is not always successful, particularly where there are strong fundamental forces operating in the opposite direction. While the Bank of Japan has succeeded in preventing the yen’s slide, we suspect that a significant appreciation will only manifest once the Federal Reserve contemplates policy loosening and expected interest rate differentials move in its favour.

Second, most other central banks do not have the firepower of the Bank of Japan, which has $1.2trn (27% of GDP) in FX reserves. The Bank of England, for example, holds reserves equivalent to a more modest 4% of GDP. Third, other central banks have the more effective interest rate tool at their disposal and so have less need to rely on FX intervention. With underlying inflation still weak in Japan, and given its longstanding struggles to escape a low inflation environment, the BOJ is understandably reluctant to raise interest rates. But high and rising core inflation in almost all other advanced economies gives them ample cause to hike interest rates.

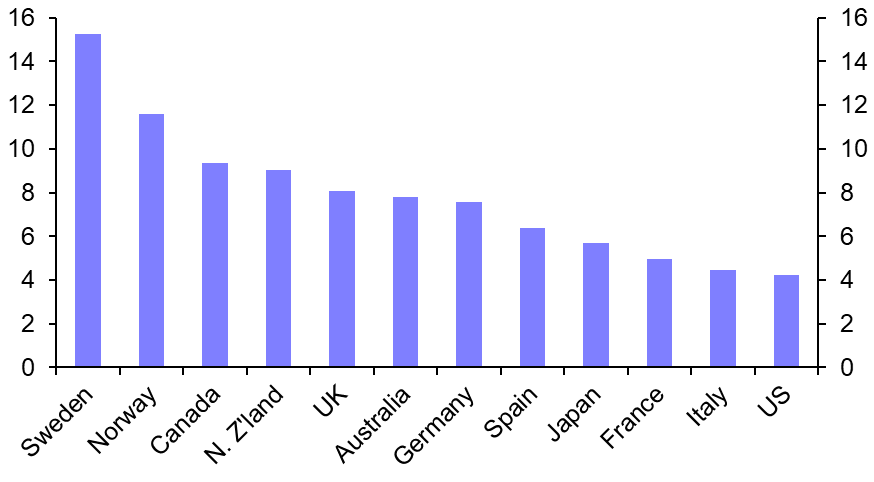

Worries over the implications of currency weakness will be greater where imports make up a high share of consumer spending, implying a bigger pass-through from currency movements to inflation. On this basis, Sweden and Norway look particularly exposed, but among major DMs, the UK looks most vulnerable to currency weakness stoking inflation. (See Chart 2.) In all, then, currency weakness against the dollar is another factor justifying further significant interest rate hikes in other advanced economies, most notably the UK.

|

Chart 2: Imports of Final Consumer Goods as a % of Private Final Consumption Expenditure (2021) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Comtrade, Capital Economics |

Politics throw a spanner in the works

Political developments have also made some central banks’ jobs more difficult in recent weeks. In Europe in particular, while central banks are tightening policy to tackle high inflation, governments are announcing policy support, partly to shield firms and households from the effects of rising gas prices.

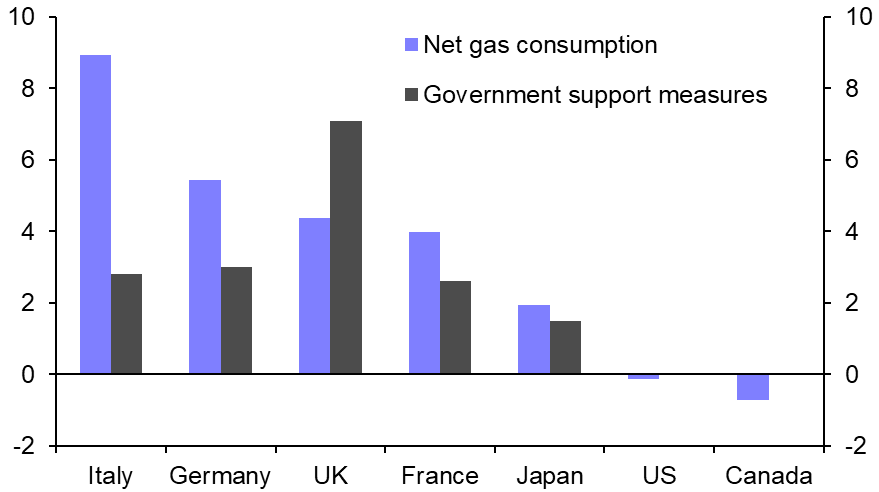

This policy contrast is greatest in the UK, where the government has announced fiscal measures equal to 7% of GDP. Admittedly, the UK economy has been hit particularly hard by rising gas prices. But as Chart 3 shows, we estimate that (if left unchecked) the rise in wholesale prices would have raised the cost of net gas consumption by a sum equivalent to less than 5% of GDP. So the fiscal support goes beyond that which is justified to “fill the hole”. In an environment where deficient supply rather than demand is holding back activity, such stimulus will add to price pressures. So while the government’s energy price cap will mean that the peak in headline inflation is lower than it would otherwise have been, the Bank of England is understandably focused on the medium term inflationary implications of blanket tax cuts. We now see it raising interest rates to a peak of 5%. (See here.)

|

Chart 3: Rise in Cost of Energy & Fiscal Measures |

|

|

|

Source: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Governments elsewhere have not made life quite so difficult for their central banks. The challenge of rising natural gas prices just does not apply to the US or Canada. And in Japan and the euro-zone, policy support has not exceeded the cost associated with higher gas prices. But the Italian election has ensured that the ECB’s role is not plain sailing either. As we explained here, the fact that the country will be governed by a group of historically euro-sceptic parties under an untested leadership raises the risk of a loss of confidence in Italy’s public finances in future. Any sign of slippage relative to fiscal or reform commitments could make it very difficult for the ECB to use its new Transmission Protection Instrument to prevent a rise in bond spreads as policy rates rise.

Erring on the side of caution?

So what does it all mean for policy? The first point is that interest rates now look set to rise even more sharply than we had previously envisaged. Details are set out in Table 1. But, in short, we now expect the average policy rate among advanced economies to rise by 365bps from trough to peak, which would be the most aggressive tightening since the Volcker shock. A second point is that recent developments have strengthened our conviction that the US Federal Reserve will pivot before most other central banks given the strength of the dollar and growing evidence that US inflation is set to fall.

The third point is that amid growing scepticism about their credibility and great uncertainty over how long price pressures will persist, there is a growing risk that central banks will err on the side of caution by overtightening. We have already argued that policy tightening will cause a modest global recession, but the risk is that rate hikes beyond our expectations prompt an even deeper downturn.

Monetary Policy Developments

Review of recent policy changes

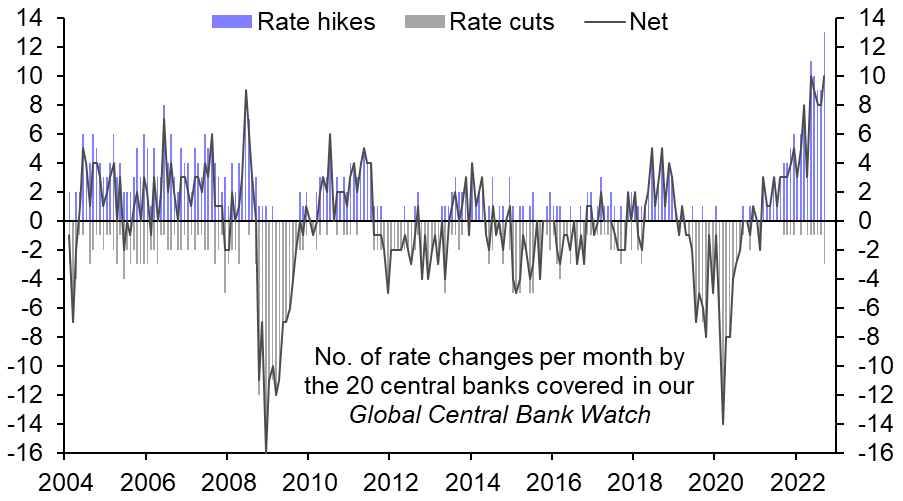

The ongoing global tightening cycle has seen another 21 rate hikes across the 20 economies covered by our Global Central Bank Watch in August and September. In this time, there were only four rate cuts, two of which were in Turkey, with one in both Russia and China. (See Chart 4.)

|

Chart 4: Changes in Policy Interest Rates |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

The size of interest rate hikes have generally been in line with or above market expectations. Some central banks upped the pace of tightening, including the ECB and the SNB hiking by 75bp and Sweden’s Riksbank hiking by a surprise 100bp. Others hiked at a steady pace, including the Fed hiking by another 75bp, and the Bank of England, and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand each hiking by another 50bp. The Bank of Canada pared back the pace of tightening, opting for a 75bp hike in September rather than its previous 100bp hike, owing to GDP in Q2 being weaker than the Bank expected. And, the Reserve Bank of Australia was the only advanced economy central bank to deliver a smaller-than-expected rate hike, slowing the pace of tightening from 50 to 25bp amid concerns about the outlook for the global economy.

DM tightening cycles in full swing, for now

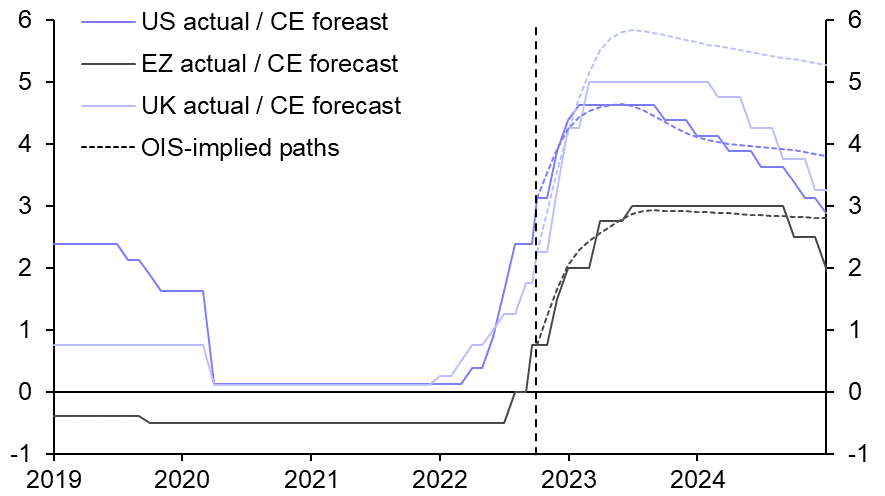

Policymakers remain hawkish and rate hikes look set to continue at pace in the near term, but most central banks outside Europe will pivot before the end of 2023 as inflation falls and activity weakens. We expect the Fed to hike by another 75bp in November and 50bp in December, and to take the funds rate to a peak of 4.50-4.75% in Q1. But by the middle of 2023, price pressures should have eased enough for the Fed to cut rates back towards neutral levels in the second half of next year, which is a view seemingly shared by investors. (See Chart 5.)

|

Chart 5: Policy Rates (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

We expect a 75 or 100bp hike by the ECB in October, and – following the announced fiscal loosening in the UK – the BoE looks set to hike rates by 100bp in November and a further 75bp in February. But unlike in other DMs, interest rate cuts in Europe are unlikely to come onto the table until 2024 given their stronger inflationary pressures.

As for balance policy, most DM central banks are continuing to turn towards net asset disposals, with the Fed doubling its pace of quantitative tightening in September, and the Bank of Japan’s assets falling for the first time since 2013. The ECB is holding talks about shrinking its balance sheet in October, and, while they have yet to announce a schedule for their plan, the shift is expected to begin early next year. However, concerns over financial stability have led the BoE to restart gilt purchases, with plans for quantitative tightening delayed until 31st October.

Hikes end in some EMs, some currency risks remain

Tightening cycles in some EMs outside Asia seem to be coming to a close as inflationary pressures ease. In Emerging Europe, the central banks of Poland and Hungary stated that they have finished tightening the screws, and we suspect that the Czech central bank is done with rate hikes now too. In Latin America, while currency pressures present further inflationary risks, headline rates have either peaked or are close to peaking. Big falls in inflation in Brazil have caused policymakers there to draw their tightening cycle to a close, and we expect most other central banks in the region to follow suit over the coming months.

However, in parts of Asia, a strong US dollar is putting particular pressure on policymakers to raise interest rates given concerns about foreign-currency debt and the passthrough to inflation. The central banks of Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam all recently cited the risk of further currency falls as reasons for their rate hikes, and we have revised up rate forecasts accordingly. Finally, we expect the PBOC to continue to sit out the global tightening cycle. We still think that policy rates there will be trimmed a little further. But the relaxation of the mortgage interest rate floor has weakened the case for more rate cuts in the near term. So, we have pushed back our expectation for the timing of next cut to the 1-year Loan Prime rate into Q1 next year.

|

Table 1: Central Bank Hub |

|||||||

|

Country |

Next Meeting |

Policy Rate |

Next Change |

End-2022 |

End-2023 |

End-2024 |

Balance Sheet |

|

Major Advanced Economies |

|||||||

|

2 Nov. |

3.00-3.25 |

+75bp (Nov. 2022) |

4.25-4.50 |

4.00-4.25 |

2.75-3.00 |

Balance sheet run-off has begun - pace to reach $120bn next year. |

|

|

27 Oct. |

0.75 |

+75bp (Oct. 2022) |

2.00 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

Will have to use new Transmission Protection Instrument to keep peripheral spreads under control. |

|

|

28 Oct. |

-0.10 |

None on horizon |

-0.10 |

-0.10 |

-0.10 |

Balance sheet will shrink slightly as emergency loans are repaid and continued gross bond purchases are broadly offset by bond redemptions. |

|

|

3 Nov. |

2.25 |

+50bp (Nov. 2022) |

4.25 |

5.00 |

3.25 |

BoE selling £10bn of gilts per quarter |

|

|

26 Oct. |

3.25 |

+50bp (Oct. 2022) |

4.00 |

3.00 |

2.50 |

Stopped reinvesting maturing bonds in April. With 40% of the Bank's holdings set to mature within two years, active bond sales are unlikely. |

|

|

1 Nov. |

2.60 |

+25bp (Nov. 2022) |

3.10 |

3.35 |

3.10 |

Bank will allow bond holdings to run off, but no outright sales. |

|

|

15 Dec. |

0.5 |

+50bp (Dec. 2022) |

1.00 |

1.25 |

0.75 |

Very little anticipated, unless franc appreciates. |

|

|

23 Nov. |

1.75 |

+75bp (Nov. 2022) |

2.50 |

2.50 |

2.00 |

Asset sales to begin by end-2022. |

|

|

3 Nov. |

2.25 |

+50bp (Nov. 2022) |

3.00 |

3.00 |

2.50 |

– |

|

|

5 Oct. |

3.00 |

+50bp (Oct. 2022) |

4.00 |

4.25 |

3.50 |

RBNZ to sell $5bn of its bond holdings every fiscal year. |

|

|

Major Emerging Economies |

|||||||

|

15 Oct. |

2.00 |

-20bp (Q1 2023) |

2.00 |

1.80 |

1.80 |

- |

|

|

7 Dec. |

5.90 |

+25bp (Dec. 2022) |

6.15 |

6.40 |

6.40 |

– |

|

|

7 Dec. |

13.75 |

-25bp (Q2 2023) |

14.00 |

11.00 |

7.50 |

– |

|

|

28 Oct. |

7.50 |

-50bp (Oct. 2022) |

7.00 |

5.50 |

5.50 |

– |

|

|

10 Nov. |

9.25 |

+75bp (Nov. 2022) |

10.00 |

9.50 |

8.50 |

– |

|

|

14 Oct. |

2.50 |

+25bp (Oct. 2022) |

3.00 |

2.50 |

2.25 |

– |

|

|

20 Oct. |

12.00 |

-50bp (Oct. 2022) |

11.50 |

28.00 |

28.00 |

– |

|

|

20 Oct. |

3.75 |

+75bp (Q4 2022) |

4.50 |

5.00 |

4.50 |

– |

|

|

5 Oct. |

6.75 |

+25bp (Oct. 2022) |

7.00 |

6.50 |

5.50 |

– |

|

|

24 Nov. |

6.25 |

+50bp (Nov. 2022) |

6.75 |

7.75 |

6.75 |

– |

|

Jennifer McKeown, Head of Global Economics Service, +44(0) 207 811 3910, jennifer.mckeown@capitaleconomics.com

Leah Fahy, Assistant Economist, +44 (0)207 808 4694, leah.fahy@capitaleconomics.com