After weeks of turbulence, a US-China agreement to slash tariffs has suddenly fuelled hopes that the worst of President Trump’s trade war is behind us. That’s certainly been the interpretation in financial markets, where risk assets have more than clawed back their ‘Liberation Day’ losses.

Given how close the global economy was brought to the brink, the wave of relief in markets is understandable. But caution is still warranted: Trump’s global trade truce is fragile, with flashpoints on several fronts.

One of the most immediate is the 8th July expiry of the original 90-day pause on “reciprocal” US tariffs on its trading partners. The corresponding 90-day pause on tariffs on China that was agreed in Geneva will then expire on 12th August. If these countries are unable to come to agreement with the US ahead of these dates then tariff rates could theoretically snap back to their 2nd April levels – raising the effective US tariff rate by 7 percentage points.

A more likely outcome is that these deadlines will simply be rolled over. But even if extensions are granted, markets may face renewed volatility as the administration takes negotiations down to the wire.

The art of the deals

Efforts to secure agreements with Canada and Mexico are an obvious focus given their deep integration into US supply chains. A full renegotiation of the USMCA is not due until next year, but all three governments have floated the idea of bringing talks forward. The most likely outcome is that the agreement will survive with only modest adjustments. But a lot hinges on what the US wants to achieve. If the administration decides to pursue more radical objectives – for example incentivising the relocation of auto production to the US, or substantially tightening rules of origin to prevent the tariff-free shipment of non-USMCA goods to America via Mexico – then talks could become more protracted.

Trade talks with other allies appear, at least on the surface, more straightforward. Voices within the administration have suggested that agreements with Korea, Australia and India are likely to materialise in some form. But negotiations with the EU are more complex. The bloc’s large trade surplus with the US, combined with its style of government by consensus, will make it harder for it to agree a deal with Washington. This could emerge as a key point of friction in the months ahead. Likewise, a deal with Japan no longer appears within easy reach, with Tokyo now reportedly pushing for a more substantial rollback of auto tariffs.

At the same time, sector-specific investigations under Section 232 investigations are another source of potential risk. Probes into industries ranging from semiconductors to pharmaceuticals could result in new tariffs being imposed – perhaps suddenly, and with little warning. The administration has shown restraint so far, likely aware of the potential for an adverse market reaction. But that restraint is not guaranteed to hold, especially if more confrontational voices within the administration regain influence.

Semiconductors are the most globally sensitive sector. Tariffs here would have ripple effects across global supply chains, hammering economies such as Taiwan, Malaysia and Vietnam. Conversely, pharmaceutical tariffs would have a more limited macroeconomic impact, although key exporters like Ireland and Switzerland remain exposed.

Beyond tariffs themselves, a growing concern is the extent to which the US is using bilateral trade deals to isolate China. The US-UK agreement, for instance, includes provisions that appear designed to exclude Chinese firms from strategic supply chains. If replicated in other deals, this approach could entrench geopolitical divisions and put any broad reconciliation between Washington and Beijing even further out of reach.

Still a US-China story

Indeed, the greatest long-term risk to global trade flows remains the US-China relationship. While recent moves suggest a desire to de-escalate, fundamental disagreements remain unaddressed. Issues such as intellectual property, subsidies and exchange rate management have yet to be broached. More fundamentally, the superpower rivalry between the US and China has moved beyond trade into technology, security and critical minerals. Even if both sides reach temporary understandings on tariffs, these underlying tensions are unlikely to dissipate. The structural divergence between the two economies makes a comprehensive agreement increasingly improbable.

Cutting across all of this is a delicately poised dynamic within the White House. While Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent is now in ascendancy and steering trade policy, this could change. There’s no guarantee that hardliners like Peter Navarro – who have long opposed the dialogue-based approach now being revived – will remain sidelined.

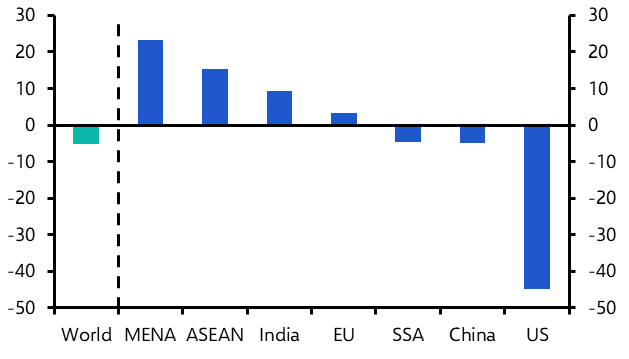

Nonetheless, our base case remains that the eventual tariff regime will resemble today’s: elevated but moderate duties on most trading partners, but significantly higher tariffs on Chinese goods. Yet this assumption rests on a fragile foundation – not least that the president continues to heed more moderate voices. Should that balance shift, the tentative truce could collapse.

A glass half full?

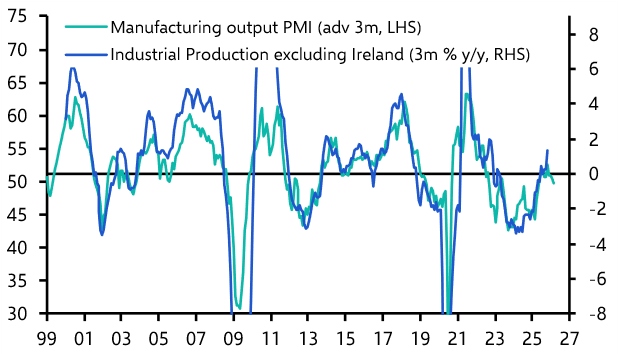

If all of that sounds excessively bearish, then readers can take comfort from the fact that the reports that tariffs are already inflicting substantial damage on the global economy appear overdone. You can see how tariffs are feeding through the global trade cycle via our ‘Global Trade Stress Monitor’. This tracks activity through seven key stages of the trade cycle – from orders, to production, to shipment, and onwards. It shows some evidence of modest disruption at the early stages of the cycle. But conditions further along the cycle remain normal, helped in part by the fact that firms were able to “front run” tariffs earlier this year (the Monitor will be updated on a weekly basis.)

The upshot is a fragile trade truce, with economic fallout that has, for now, remained relatively limited.

In case you missed it:

- Paul Dales explores how far the UK could go in its reset of relations with the EU. The report is part of our Future of Europe project, which includes data and analysis on issues ranging from fiscal risks to financial market repricing to EU expansion.

- Gold prices may have come off the boil in recent weeks, but forces are at work that could take them to fresh record highs later in the year, says Hamad Hussain.

Although Javier Milei has done a good job in turning Argentina around, the consensus has become too optimistic about how much the economy will grow, says Kimberley Sperrfechter.