President Trump has described the Supreme Court case over his tariff regime – with characteristic restraint – as “literally, LIFE OR DEATH for our Country”. Hyperbole aside, the stakes are indeed high. The Court’s decision, which may not come for several months, will have far-reaching economic consequences. Early indications suggest the justices are sceptical of the administration’s arguments.

Even so, should the ruling go against the White House, it’s hard to imagine the tariffs being scrapped entirely. More likely, the administration would find a way – however messy or temporary – to preserve them. At present, the tariffs are delivering revenues worth roughly 1% of GDP annually to the US Treasury. That windfall has helped prevent a federal deficit that’s already hovering around a bloated 6% of GDP from widening further as a result of this year’s “One Big Beautiful Bill” of tax cuts.

A ruling against the tariffs would hit federal finances on two fronts: the government would lose the ongoing revenue from higher import duties and could also be forced to refund duties already collected. That would leave the administration facing an unenviable choice: cut spending, raise other taxes, or allow the deficit to swell toward 7% of GDP. Either way, it risks angering Trump’s supporters and unsettling the bond vigilantes.

The broader point is that the US has, almost by stealth, come to rely on tariff revenues as a quasi-permanent source of fiscal support. That dependence makes it highly likely the administration will seek to preserve them, one way or another – and increases the chances that they persist under future administrations too.

The art of the deal to reshape global order

Even as the Court weighs the future of Trump’s tariff policies, three new trade deals point to the shape of the global system now forming. The most high-profile was between the US and China, announced by Presidents Trump and Xi two weeks ago. Any optimism has been overdone. Superficially, it looks promising: China will ease planned restrictions on rare earth exports, while the US has delayed expanding its Entity List, which restricts exports for specific companies and organisations. Washington also pledged a 10% cut to tariffs imposed on China over its perceived failure to stem fentanyl flows into the US, and said Beijing had agreed to stop shipments of chemicals used to produce the drug (the Chinese read-out was more circumspect, referring only to a “consensus on fentanyl counternarcotics cooperation.”)

Yet the optics are far stronger than the substance. Both sides have essentially bought time. Tariffs remain substantially higher than at the start of the year, and the underlying relationship is no less adversarial. In truth, this is little more than a truce – it does nothing to correct the deeper imbalances that underpin global trade, notably over-consumption in the US and chronic under-consumption in China.

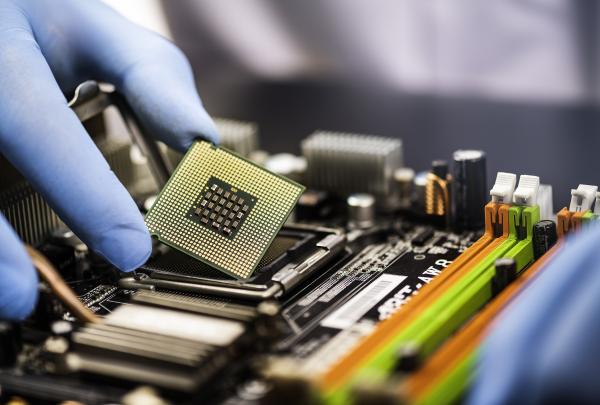

The other two US deals, with Malaysia and Cambodia, drew far less attention internationally but spoke volumes about where White House trade policy is heading. Both economies are heavily dependent on US demand – Malaysia through high-tech electronics, and Cambodia through clothing and textiles. Strikingly, both agreements contain sections on ‘Economic and National Security’ that attempt to pull each country into Washington’s strategic orbit.

The Malaysia deal, for instance, stipulates that if the US imposes import restrictions in the name of national or economic security, Kuala Lumpur must adopt “equivalent” measures, or agree a timeline to do so that is acceptable to Washington. It also commits Malaysia to align its export controls with those of the US and limits its ability to strike deals with countries “of concern” – in other words, China. A clause which encourages shipbuilding “by market economy countries” appears also deliberately aimed at China, and is emblematic of Washington’s focus on strategically important sectors.

There are carrots as well as sticks. The agreement notes that if the US deems Malaysia “to be cooperating to address shared national and economic security issues, the United States may take such cooperation into account in administering its domestic laws and regulations pertaining to export controls, investment reviews, and other measures”. In other words: play nicely and we’ll reward you.

Some observers dismiss these provisions as vague or unenforceable, or argue that the countries involved will find ways to straddle both sides of the US-China divide. In Malaysia, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s government has sought to calm domestic criticism by pointing to the deal’s exit clause. And the fact that, just days after signing with the US, Malaysia also joined an updated ASEAN-China free trade agreement reinforces the view that many economies will continue to hedge between the two blocs in an increasingly fractured global system.

But I think this misreads what’s going on. As I argue in The Fractured Age, it will be the US and China – not the smaller economies – that determine the degree to which others will be able to remain unaligned. Malaysia’s room for manoeuvre is limited.

The shape of things to come

Taken together, these agreements provide a blueprint for what trade diplomacy will look like in a fractured world – one shaped less by multilateral institutions and more by strategic leverage. Expect more of the same to follow, across ASEAN and beyond. The result will not necessarily be less global trade, but rather trade that is increasingly politically driven –shaped as much by allegiance and ideology as by economics.

Related content

- Our US team weighed the legal risks to the current tariffs regime, and the administration’s alternatives.

- Senior Asia Economist Gareth Leather showed why concerns about the macroeconomic impact of the recent surge in the Malaysian ringgit are misplaced.

- Our UK team outlined the likely macro and market consequences of this month’s Budget.