One of the more dispiriting aspects of the US–China trade war is the insistence from both Washington and Beijing that they are “winning.” The truth, of course, is that no one wins a trade war. Yet the selective – and often dubious – data used to make these claims do tell us something about how the conflict is reshaping global trade patterns, and how the global economy as a whole is continuing to muddle through.

Let’s start with the narrative from Washington. The US points to the collapse in imports from China as proof that tariffs are “working”.

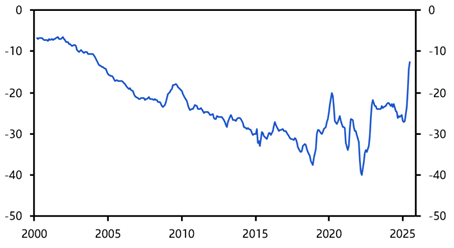

Chinese exports to the US have fallen by 30% since January, while the US trade deficit with China is the smallest since shortly after it joined the WTO in 2001. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: US Trade Deficit with China ($bn, seasonally-adjusted, 3m average) Sources: CEIC, Capital Economics |

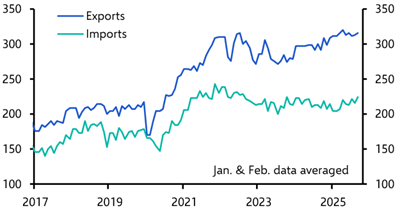

But step back and the picture looks rather different. China’s overall exports are holding up surprisingly well. September’s data show exports running at near-record highs and growing at 8% y/y. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: China Goods Trade ($bn, seasonally adjusted) Sources: CEIC, Capital Economics |

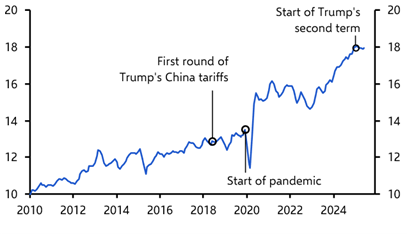

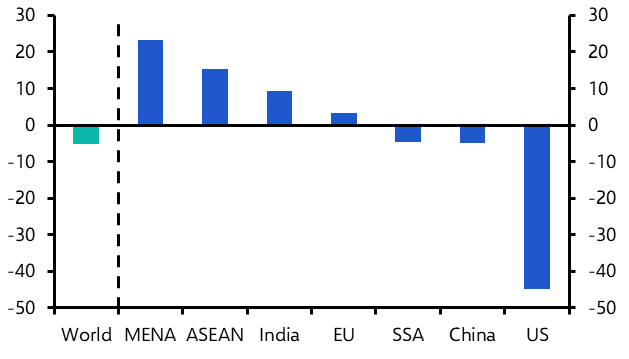

More striking still, China’s share of global export volumes has climbed from 12% in 2018, when tariffs were first imposed during the first Trump administration, to roughly 18% today. (See Chart 3.) In other words, while Chinese firms have lost ground in the US, they have gained it elsewhere. Despite tariffs and tightening restrictions, China’s exporters have, by and large, adapted remarkably well.

|

Chart 3: China’s Share of Global Export Volumes (%, 3m Average)

Sources: CEIC, Capital Economics |

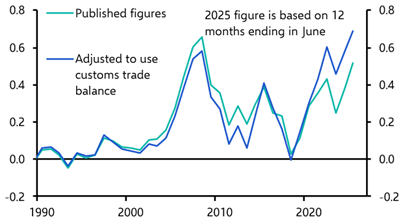

China’s official balance of payments data are distorted by the treatment of contract manufacturing by outsourcing firms. But our adjusted series shows that its current account surplus now stands at a record $821bn for the 12 months ending in June – larger relative to the size of the global economy than it was on the eve of the Global Financial Crisis in 2007. (See Chart 4.)

|

Chart 4: China Current Account Surplus (% of global GDP) Sources: CEIC, Capital Economics |

The sheer size of China’s economy means that if it runs a large external surplus then the US (as the world’s largest economy) will in practice have to run a large deficit. Sure enough, America’s current account deficit is running at around $1.2trn, or roughly 4% of GDP.

Squaring the circle

At first glance, these facts don’t seem to add up. How can America’s bilateral deficit with China have narrowed so sharply, while its overall deficit remains stubbornly large? And by the same token, how can China’s surplus with the US have shrunk, while its overall surplus has expanded?

There is some evidence that emerging economies are now starting to absorb more of China’s surplus. Similarly, it is likely that some goods are being rerouted from China to the US via lower-tariff countries, although according to our estimates this isn’t happening as much as during the first trade war in Trump’s previous administration. But these explanations offer only part of the answer. Stepping back, the key point is that the US, by running a deficit, is providing demand to the rest of the world. The rest of the world, in turn, is then able to provide demand to China. Accordingly, China is able to run a large external surplus, even though its bilateral surplus with the world’s largest consumer (and importer) has collapsed.

This framing is crucial when thinking about the potential impact of the 100% tariff on Chinese imports that President Trump has recently threatened in response to Beijing’s move to tighten restrictions on rare earth exports. The key question is whether tariffs at these levels would reduce America’s overall demand for imported goods, or merely shift it away from China. If it’s the former, the global economy would feel the pain. If the latter, then firms with supply chains that run through China would experience disruption, but the wider economic impact (including on the China itself) might be relatively modest if demand elsewhere in the world adjusts.

Thinking in aggregate

The lesson is that tariffs can – and do – distort bilateral trade flows, sometimes dramatically. This can have profound economic consequences for some firms. For example, tariffs can shift demand for different shipping routes, and they can embed additional costs in global supply chains that are affected by them. But tariffs do not determine overall trade balances. Those are set by the balance of savings and investment in every economy.

The bottom line is that as long as the US continues to run large fiscal deficits and private sector demand remains healthy it will continue to run large trade and current account deficits. Likewise, as long as Chinese households save heavily and domestic consumption remains subdued, China will continue to run large trade and current account surpluses.

Unless one or both of these structural imbalances change – say, through fiscal restraint in the US or a concerted effort in China to boost household incomes and consumption – the global economy will remain in its current configuration: one giant deficit country, one giant surplus country, and trade flows that bend and twist to accommodate them.

Still dependent on US demand

The counterpart to this is that the rest of the world remains dependent on US demand. For now, that support remains firm: we estimate that robust household spending and a surge in AI-related investment meant that US private sector demand grew by 3.6% q/q annualised in Q3. Our base case is for continued strength, with growth in private demand of around 2.5% in 2026 and 2027. But this dependence carries risk. Should US consumers retrench or business investment falter, the repercussions would send shockwaves far beyond America’s shores – including, despite that much narrower bilateral surplus with the US, to China.

In Case You Missed It:

- Fears about US bank loan books have been weighing on equities but Senior Markets Economist James Reilly explains why this isn’t a repeat of 2023’s mini banking crisis.

- Europe Economist Adrian Prettejohn showed why the region is getting left behind in the great AI investment boom.

- The Financial Times recently featured this June analysis from Chief Asia Economist Mark Williams about what’s behind the paradox of why China is emerging as a global tech leader, even as its productivity growth rates languish.