Last week I outlined the key macro themes that are likely to shape the global economy in 2026. This week I tackle a question that has come up frequently in subsequent client meetings: What are the key risks to our view?

Ask an economist about “risks” and they’ll tend to list everything that could conceivably go wrong, from debt and banking crises to war and geopolitical strife. This is not insight, but a disclaimer – a kind of “get out jail free” card for forecasters.

A more useful way to consider key risks is not to provide a long list of possible threats, but to ask which developments would actually force a rethink of the central forecast. Most shocks do not alter the macro story. A few do.

Financial shocks matter most

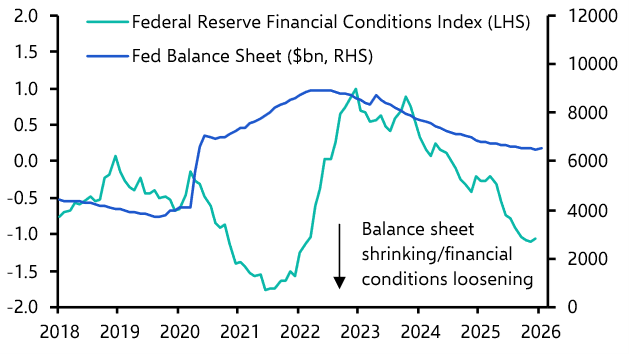

Let’s start with the financial system, since that is usually where major economic shocks originate. The regulated banking system today looks better capitalised and less leveraged than it has done before previous crises. This does not make it bomb-proof, but it does mean the banking system is less obviously a weak link. If trouble is coming, it is more likely to emerge from the shadowy parts of the system, in particular private credit and related structures that have grown rapidly in size and importance in recent years, and yet remain lightly supervised.

A crisis in private credit is not inevitable – far from it. But the combination of leverage and illiquidity rarely ends well when growth slows. With that said, problems in private credit would only matter from a macroeconomic perspective if they were large enough, or contagious enough, to infect the broader financial system and cause credit conditions more generally to tighten. A single fund blowing up is not a serious macro headwind. A freezing of wider credit markets is.

Outside of private credit, the other obvious potential macro-financial risk is a sharp sell-off in equity markets. After a long rally, and with valuations approaching dotcom levels, it would only take a couple of missed earnings targets to puncture confidence. A sharp decline in share prices would erode household wealth and weaken corporate balance sheets, with predictable consequences for consumption and investment.

Yet it is easy to overstate the economic fall-out from a market correction. Some equity markets look expensive, but that does not mean they are poised for collapse. If anything, valuations could well become more stretched before they retreat to more normal levels. And even when equity prices do fall, the effect on real activity is typically modest. As a broad rule of thumb, a 10% fall in equity prices tends to knock only a couple of tenths of a percent off GDP. Markets often behave as though a correction is an economic event in itself. In reality, it usually takes something more than falling share prices to cause a recession.

Could inflation stage a comeback?

Inflation remains another key macro risk. Markets are assuming that inflation will trend lower in 2026 and that interest rates will come down in most countries. Indeed, this is what we are forecasting too. But the experience of the past few years should make us wary of assuming that inflation will behave in predictable ways.

One risk is that demand simply stays stronger than expected, resulting in stronger inflationary pressures. That would complicate the path of monetary easing but would hardly be a disaster for economic growth. More uncomfortable would be renewed supply-side dislocation – for example from trade disruption or a spike in commodity prices – or a shift in inflation expectations that caused wage growth and thus core inflation to remain stubbornly strong. If either materialised then it is likely that monetary policy would remain tight even as activity weakened. To be clear, this is not the most likely outcome, but it is the type of shift that changes the entire policy environment in a way markets tend to underestimate.

Watch the US labour market

The biggest economic shock, however, may not come from the upside risks to inflation but from the downside risks to growth, particularly in the US. Our above-consensus GDP forecast for the US in 2026 rests on two assumptions: that American productivity continues to surprise on the upside, and that softer employment does not translate into a meaningful pullback in consumer spending.

If productivity disappoints just as the labour market cools, the danger is that weaker job growth causes a pullback in household spending, which in turn causes a further drop in employment and a deeper retrenchment in consumption. For an economy as critical to the global outlook as the US, that is the clearest downside risk to the outlook.

It’s the politics, stupid

Political risk also deserves to be taken seriously – not in the abstract, but in its interaction with public finances and investor confidence. The UK’s lesson of recent years is that bond markets are less concerned about the precise mix of tax and spending but whether there are credible constraints around fiscal policy. When those constraints are in doubt, sentiment can shift with startling speed.

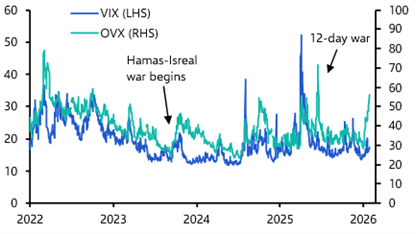

This is not to say that every political shift is necessarily a major macro event. Rather, it is to say that in a world of high public debt and rising interest costs, fiscal credibility has become the glue required to hold the public finances together. Political shocks that cast doubt over a government’s commitment to fiscal discipline can provoke a sell-off in bond markets and a tightening in financial conditions, which in turn weighs on economic growth and adds to concerns over fiscal sustainability. Potential triggers over the next 12 months include concerns about the outcome of the 2027 presidential elections in France, a potential change in government in the UK, and a ruling against tariffs by the US Supreme Court that could force the Trump administration to refund revenues to importers and blow a hole in the federal government budget.

Monetary credibility is equally important, and could also come into question next year. Our forecasts assume that whoever is chosen to replace Jerome Powell as Chair of the Federal Reserve will continue to run monetary policy in a relatively orthodox way. But we could be wrong. Likewise, it is possible that the Supreme Court upholds the Administration’s decision to fire Fed Governor Lisa Cook, paving the way for greater politicisation of the FOMC. If this were to materialise then yields at the long end of the curve would presumably rise, creating both a headwind for the US economy, but also threatening a broader fall in asset prices and potentially feeding renewed concerns about fiscal sustainability.

And it goes without saying that all of the risks to watch in 2026 are also correlated. The materialisation of one could catalyse others, while external shocks could trigger cascading effects that amplify vulnerabilities across the system.

Thinking positive thoughts

So far, so gloomy. But it is worth ending on a reminder that risks do not all point in the same direction. Economists are a gloomy bunch, yet economies have a habit of quietly doing better than expected.

The most interesting upside possibility for 2026 is that the recent improvement in US productivity is a harbinger of a more durable and widespread upswing in productivity driven by the continued rollout of AI technology that starts to spread to other countries. That is not our base case for 2026. But it is the kind of risk investors should welcome because productivity booms have a habit of changing the economic game entirely.

In Case You Missed It

- Join us for online Drop-In briefings this coming Wednesday to hear more about the risks – and opportunities – in global macro and markets in 2026. Register here.

- We also have a special briefing after the Fed meeting on Wednesday to assess what could be one of the more contentious votes in years and gauge the 2026 policy outlook. Register here.

- Deputy Chief Euro-Zone Economist Jack Allen-Reynolds explained why ECB easing has done little to boost euro-zone GDP – and nor will the further rate cuts we’re expecting in 2026.