Is the widow-maker out of business? For years, investor bets that yields on Japanese government bonds (JGBs) would rise from rock-bottom levels were routinely crushed by the Bank of Japan’s determination to keep rates down. The fortunes lost shorting these bonds gave rise to the trade’s “widow-maker” moniker. Recent events, however, suggest that this label may no longer be deserved.

For those who were not consumed by developments in Davos, last week was marked by an extraordinary convulsion in Japan’s government bond market, concentrated at the ultra-long end of the curve.

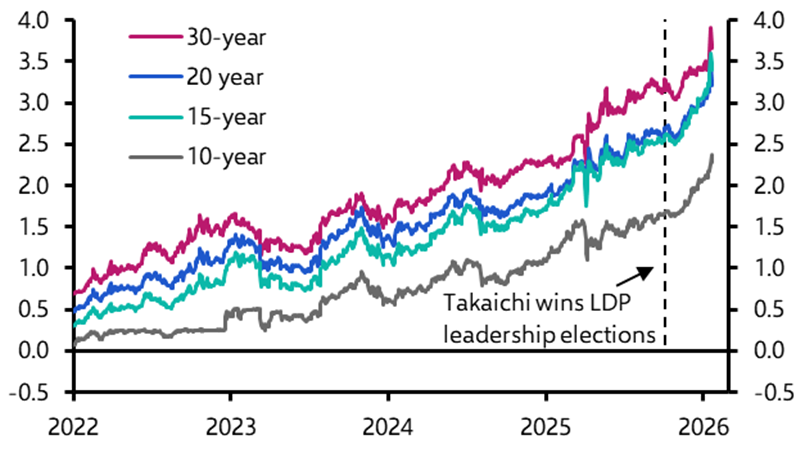

The 30-year JGB yield jumped by around 30 basis points to above 3.8%, while the 40-year rose to over 4%, record levels for both maturities. The counterpart to these moves was a plunge in prices and big returns for anyone betting against these bonds (yields on both have since eased back a little, helped by speculation about a joint US-Japan intervention to support the yen).

|

Chart 1: JGB Yields (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

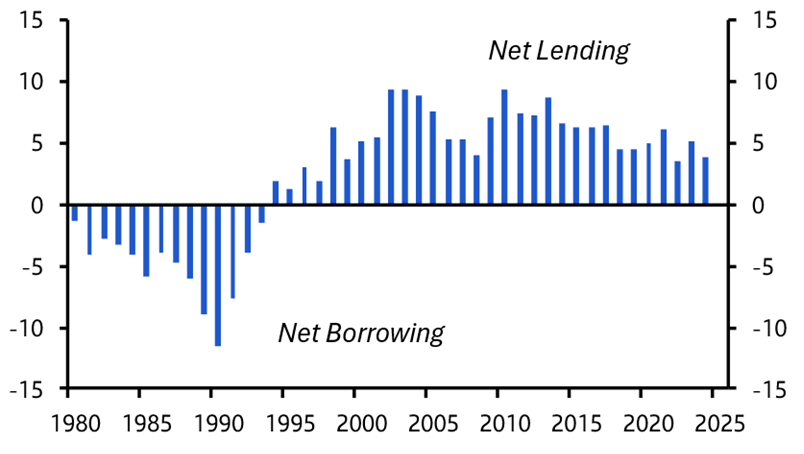

JGB yields have been moving higher across the curve for some time, but have accelerated since Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi won the Liberal Democratic Party leadership election in October. (See Chart 1.)

The immediate trigger for the latest sell-off was political too: in announcing snap elections for Japan’s lower-house next month, Takaichi pledged to “break free of the spell of excessive fiscal austerity” with a platform of tax cuts and higher defence spending. With the prime minister riding high in the polls, the implication is that Japan is heading for a substantial fiscal expansion.

Not such a fiscal basket case

One explanation for the bond sell-off, then, was that investors have been fretting about a renewed deterioration in Japan’s public finances. Both the Japanese and English-language press have warned the country risks a repeat of the 2022 ‘Liz Truss moment’, when unfunded spending plans plunged the UK into a fiscal crisis – something that Takaichi herself has denied she would bring upon Japan.

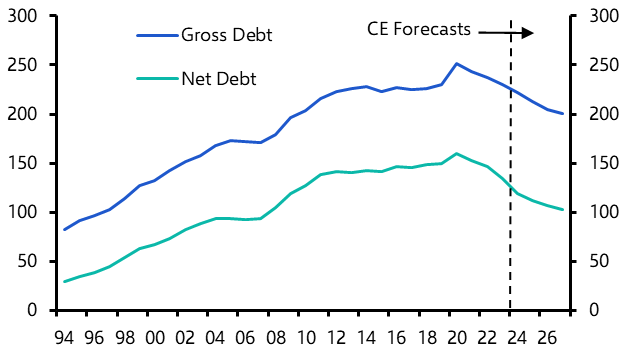

Concerns about a fiscal crisis are amplified by Japan’s well-known and eye-watering debt burden: gross government debt has exceeded 200% of GDP for the past 15 years, while net government debt has been well above 100% in that time.

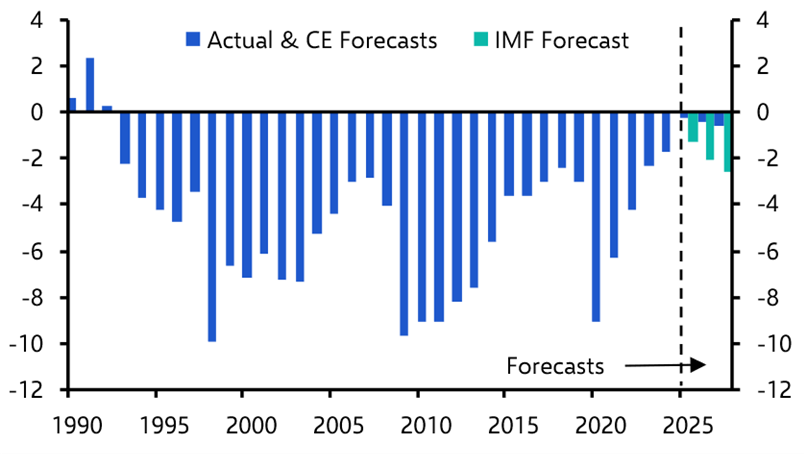

But the country’s true fiscal position may not be as grim as suggested by those headline numbers. Real-time analysis of Japan’s fiscal position is complicated by the long lag in official data. But our own high-frequency proxies for government spending and revenues, which use the more timely quarterly data (available to clients on our platform), paint a more reassuring picture. While the IMF and others estimate that the government ran a deficit of around 2.5% of GDP last year, our estimates suggest it was closer to just 0.5%. (See Chart 2.) Even allowing for Takaichi’s proposed tax cuts, we think net government debt could fall to around 100% of GDP by the end of next year.

|

Chart 2: Japan General Government Budget Balance (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: Cabinet Office, LSEG, Capital Economics |

In short, our understanding of Japan’s true fiscal position suggests that, to the extent the sell-off at the very long end of the curve has been about fiscal concerns, it's unwarranted.

Yields under the microscope

An alternative explanation for the increase in JGB yields is a more fundamental reassessment of the outlook for economic growth, inflation and monetary policy in Japan. This has more going for it.

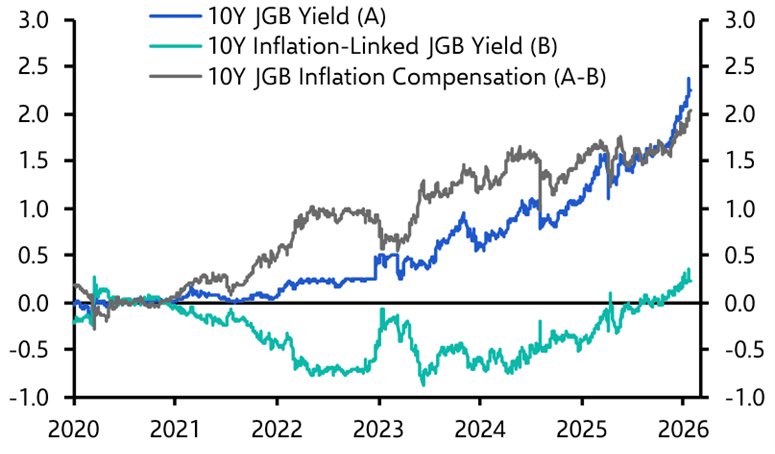

One way to think about moves in bond yields is to decompose them into inflation compensation and real yields. Inflation compensation is affected by expected inflation over the life of the bond, while real yields reflect expectations for real interest rates, which – especially for long-dated bonds – are themselves closely linked to the concept of r*, or the neutral real rate over the long term (on which, see below).

The most reliable part of the curve to perform this decomposition is probably the 10-year point on the curve. Doing so is instructive. While real yields have risen, most of the rise in nominal JGB yields over recent months appears to reflect higher inflation compensation. Since 2020, inflation compensation accounts for almost all of the rise. At present, the 10-year JGB yield is around 2.3%, of which roughly 2.0 percentage points is inflation compensation and just 0.3 percentage point is the real yield. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: 10Y JGB Yield, 10Y Inflation-Linked JGB Yield, & 10Y JGB Inflation Compensation (%/pp) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

In other words, moves in bond markets seem in large part to reflect a view that Japan’s economy is reflating, rather than facing a fiscal crisis. The obvious question is whether this optimism is justified.

Japan’s reinflationary awakening

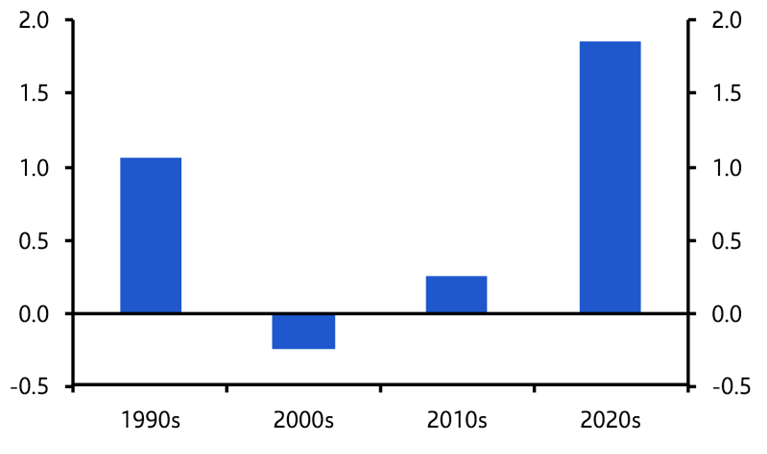

Broadly speaking, it is. While the consensus until recently had clung to the view that Japan was stuck in deflation, the reality is that this ended some time ago. (See Chart 4.) As we have argued for some time, inflation is likely to run close to the Bank of Japan’s 2% target over the coming years. While data released last week showed a sharp fall in headline inflation in December, this was due in large part to a reduction in the gasoline sales tax. Core inflation came in at 2.9% and it was striking that the BoJ revised up its forecasts for inflation in 2026 and 2027 at its meeting last Friday.

|

Chart 4: Japan CPI Inflation (%, Average) |

|

|

|

Sources: Statistics Bureau, Capital Economics. |

With inflation expectations now anchored higher, the focus shifts to how far real yields must climb to reach equilibrium, a calculation that requires grappling with the slippery concept of r*.

All other things being equal, r* should move broadly in line with potential GDP growth. This in turn depends on the growth of both productivity and the labour force. We expect productivity growth to average around 1.3% per year over the next decade. Set against this are powerful demographic headwinds: Japan’s labour force is set to contract steadily. Nonetheless, Japan’s growth prospects have improved; we think that potential real GDP growth is likely to run at around 1% per year over the next decade, up from less than 0.5% over the past decade.

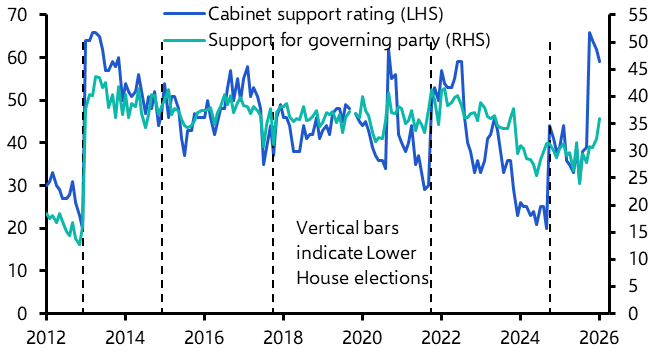

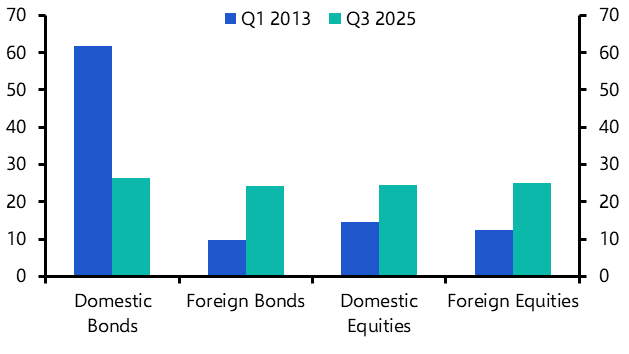

Of course, r* is not determined by potential growth alone. Structural factors also matter, particularly the balance between desired saving and investment. This also points towards an increase in neutral real rates. For decades, Japan’s corporate sector has been a large net saver, reflecting weak growth prospects and chronically subdued investment. (See Chart 5.)

If the economy is genuinely turning a corner, those surpluses should shrink as firms invest more. At the same time, an ageing population will push households beyond peak saving years and into retirement, lowering aggregate savings. Any sustained decline in savings relative to investment would also put upward pressure on the neutral real rate.

|

Chart 5: Corporations Net Lending/Borrowing (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: Cabinet Office, LSEG, Capital Economics |

The upshot is that there are good reasons to think that r* in Japan has increased. If it averages around 1% over the next decade and inflation runs at 2% then it is perfectly possible to believe that 10-year bond yields could eventually rise to 3%.

This is all to say that there is logic in the recent action in the JGB market, but not because of Takaichi’s tax and spending plans. Last week’s violent moves at the ultra-long end of the yield curve may look excessive, but there are good reasons to think that Japan’s economy is reflating. In a reflationary environment, a higher real rate and higher inflation compensation are justified, and this suggests there is scope for yields at the belly of the curve to edge higher over the next couple of years.

It also means that what once defined the widow-maker trade no longer governs the Japanese government bond market.

Note: We’re holding a special Drop-In the day after Japan’s lower-house elections to assess the results and their implications for policy and the economy. Register here for the 9th February online briefing.

Related content

The latest reading of the China Activity Proxy showed a widening gap between the government’s official GDP growth number and our own much weaker estimate of the pace of activity.

Shilan Shah previewed India’s upcoming Union Budget, a fiscal statement that is expected to reflect a difficult political environment.

The potential weaponisation of US LNG supplies to Europe is an upside risk to prices, though Hamad Hussain notes that the situation doesn’t bear comparison with what happened with Russia’s gas supplies in 2022.