What began as a political crisis risks descending into farce. Barely a week after stepping down, Sébastien Lecornu has been reappointed as France’s prime minister, the fourth in a year. The episode underscores a clear lesson: pushing meaningful deficit reduction through a fragmented parliament without a majority is next to impossible.

A fresh parliamentary election now looks increasingly likely but this may not break the deadlock. Markets are already looking ahead to the next presidential elections, due by April 2027, and to the possibility of a victory for the populist National Rally (RN), who are still leading in the polls.

A question we’re often asked by clients is what this political turbulence could mean for the real economy in France, and for the wider eurozone. Comparisons with the eurozone crisis of 2010-2015 may seem far-fetched, but they are instructive. Back then, fiscal crises in Greece and the other so-called “peripheral” economies created deep recessions and posed an existential threat to the currency union. Today, the ECB’s expanded toolkit to limit contagion means a repeat of that near-death experience is highly unlikely.

That said, persistent fiscal strains could still weigh on France’s growth prospects and, given that this is the eurozone’s second-largest economy, spill over to its neighbours. Yet even here, the parallels with the crises of 2012 are limited. As we set out in a recent Focus, there are several reasons why the economic consequences of France’s fiscal problems may not be as extreme as they seem at first sight. In particular, there are two key differences with 2012’s situation.

Doom loop risk has diminished

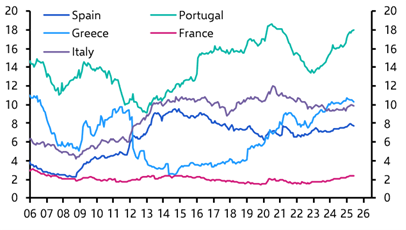

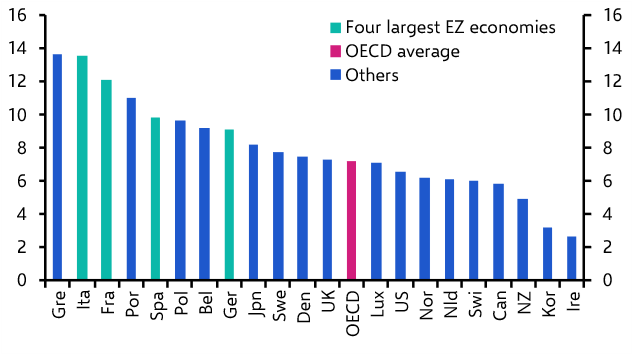

First, the channel of contagion from the banking system to the real economy is much weaker. In the early 2010s, Greek, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian banks were heavily exposed to their own governments’ debt, creating an infamous “doom loop” between sovereign and financial balance sheets. As bond prices fell, banks’ assets became impaired, feeding doubts about their solvency and amplifying fiscal fears in turn.

France is not in that position today. French government bonds account for roughly 2% of French bank assets, thus limiting the risk of a “doom loop” reigniting. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Domestic Government Bonds as a share of Total Banking Sector Assets (%) Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

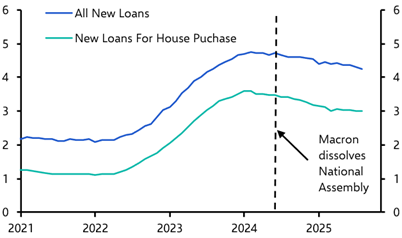

Moreover, the textbook theory that corporate borrowing costs are a function of government borrowing costs plus a risk premium is not playing out in France. Interest rates on loans charged by French banks have actually drifted lower in recent months, despite the fact that government borrowing costs have risen. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: France Interest Rates on New Bank Loans (%) Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

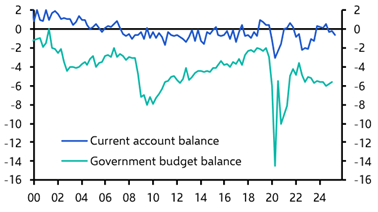

A different type of crisis

Second, the macro backdrop is entirely different in France today. Greece and others ran large budget and current account deficits, reflecting the fact that their economies were living beyond their means. Painful internal adjustments were inevitable. France’s challenge, by contrast, is fiscal rather than external. The budget deficit is running at around 5% of GDP, but the current account is broadly balanced. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: France Budget and Current Account Balance (% y/y) Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

Public sector dissaving is being offset by private sector saving. In aggregate, the French economy is not consuming more than it produces.

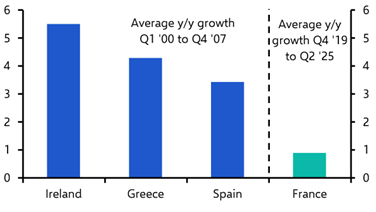

Indeed, if anything, France’s problem is anaemic growth rather than overheating. Output is expanding by barely 1% a year, in sharp contrast to the pre-crisis booms seen in southern Europe in the 2000s. (See Chart 4.)

|

Chart 4: Average Annual GDP Growth (% y/y) Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

Weak growth complicates the fiscal arithmetic, but there is no obvious need for a painful correction in private sector demand across households or firms.

None of this is to minimise the scale of France’s challenges. The political system remains paralysed, and fiscal consolidation has become a political taboo. The longer this paralysis lasts the greater the risk of a bigger sell-off in the bond markets which could force the government into a more abrupt fiscal tightening. What’s more, this creates fertile ground for populist forces that promise easy answers – and in doing so spook bond investors and make fiscal repair even harder.

It’s a toxic mix for the markets, and we expect the gap between French and German bond yields to widen as investors grow still more cautious about France’s prospects. But this isn’t 2012 all over again, and the crisis conditions seen then at the eurozone’s periphery aren’t being repeated at its core.

In Case You Missed It:

- Our China team assessed the risks of a re-escalation in the US-China trade war. Join our economists for online Drop-In briefings on this latest flare-up in tensions at 0900 BST/1600 SGT and 1000 ET/1600 BST on Tuesday.

- Our Markets team will discuss the influence of US-China trade tensions on the equities outlook in Wednesday’s asset allocation Drop-In.

- The evidence doesn’t suggest the UK economy is already feeling the heat of next month’s Budget, but Chancellor Rachel Reeves will need to take care not to undermine growth in her efforts to maintain fiscal discipline.