It wasn’t meant to turn out like this. Only a few months ago, when Donald Trump swept back into the White House, the story was one of fading US exceptionalism. The consensus view was that tariffs, tighter immigration rules and unpredictable policymaking would hobble growth in the world’s largest economy. At the same time, fiscal loosening in Germany was supposed to reinvigorate Europe’s largest economy, and stimulate growth in the region more generally.

|

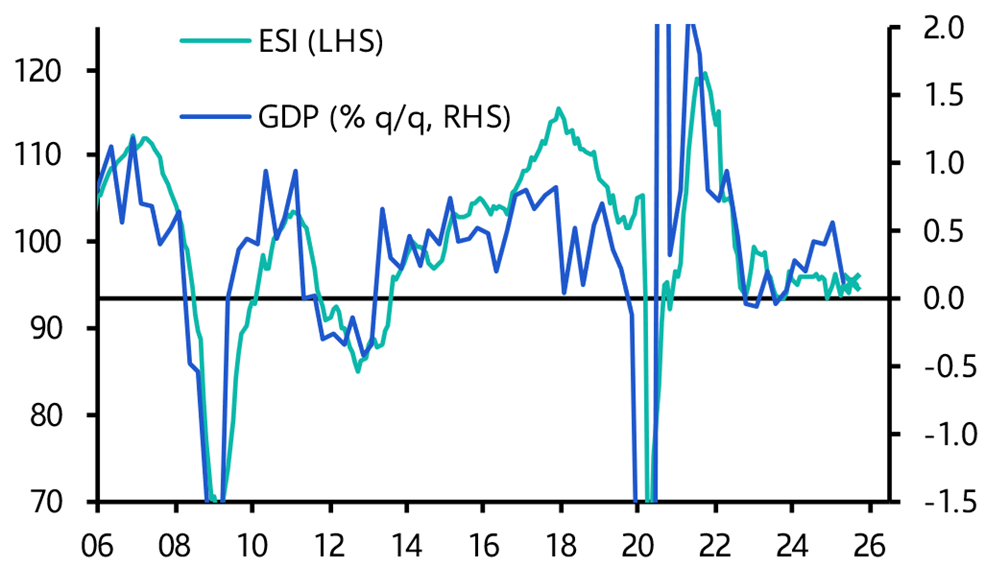

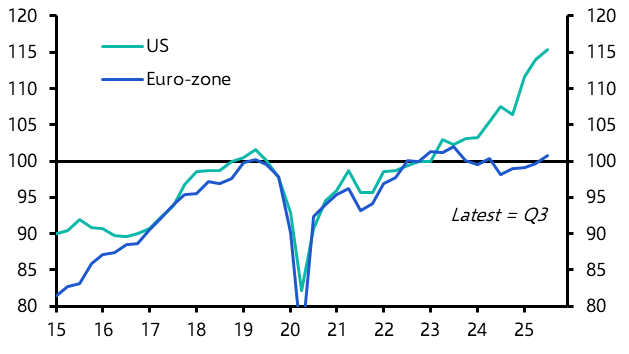

Chart 1: Euro-Zone GDP & Economic Sentiment Indicator Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

Not for the first time, the consensus has been upended.

We think that the US economy grew 0.9% q/q (or just under 4% annualised) in the third quarter. By contrast, surveys point to euro-zone GDP expanding by only around 0.1-0.2% in the most recent quarter. (See Chart 1.) How have consensus expectations been so confounded?

Misplaced optimism

The optimism towards Europe was always misplaced. Yes, the German government’s decision earlier this year to loosen the fiscal straitjacket imposed by the country’s “debt brake” was politically significant. But, as we argued at the time, the immediate economic impact was always going to be limited. Most of the fiscal relaxation was likely to happen next year rather than this, and the associated “multipliers” (which measure the change in GDP arising from a change in the government spending and taxation) were likely to be low. Developments since then have supported our scepticism. The ramp-up in spending is now not likely to happen much before the second half of 2026, and some of the additional headroom created by the relaxation of the debt brake will be used to fund the rising costs of pensions and healthcare, rather than any new programmes.

More fundamentally, the problems facing Europe’s largest economy are mainly structural and can’t be tackled with policies aimed at stimulating demand. The surge in energy costs after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine simply accelerated the long-run decline of energy-intensive industries. China has morphed from a vast market for German exports into a fierce competitor. Fiscal support cannot fix these challenges. And while Germany has some room to loosen fiscal policy, the same is not true for other major economies in Europe. France is already struggling to enact the fiscal consolidation needed to stabilise its public finances. Europe, in short, remains stuck.

Don’t bet against the US

The real surprise, though, is the US economy. It appears to have grown handily in the third quarter despite the tariffs that have sowed uncertainty in corporate America and immigration curbs that have slowed the expansion of its labour force. If that wasn’t enough, the US now has to contend with a government shutdown – although the economic impact of this is likely to be short-lived.

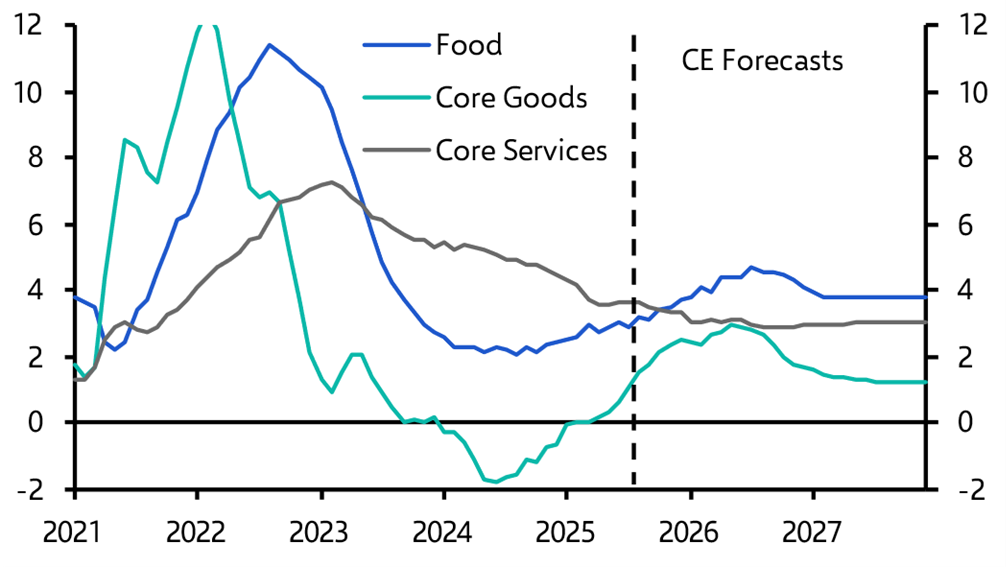

The doomsayers overstated the tariff threat. That’s not to defend the policy – tariffs distort resource allocation and stifle the gains from trade – but they were never going to topple a large, relatively closed economy. Even so, we’ve been surprised by the slow speed at which tariffs have fed through to faster goods inflation (and therefore squeezed real incomes). For now it seems that the pain is being absorbed in firms’ margins. Goods inflation is still likely to rise over the coming months, but a slowdown in services inflation could keep headline inflation broadly stable at around 3%. (See Chart 2.)

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

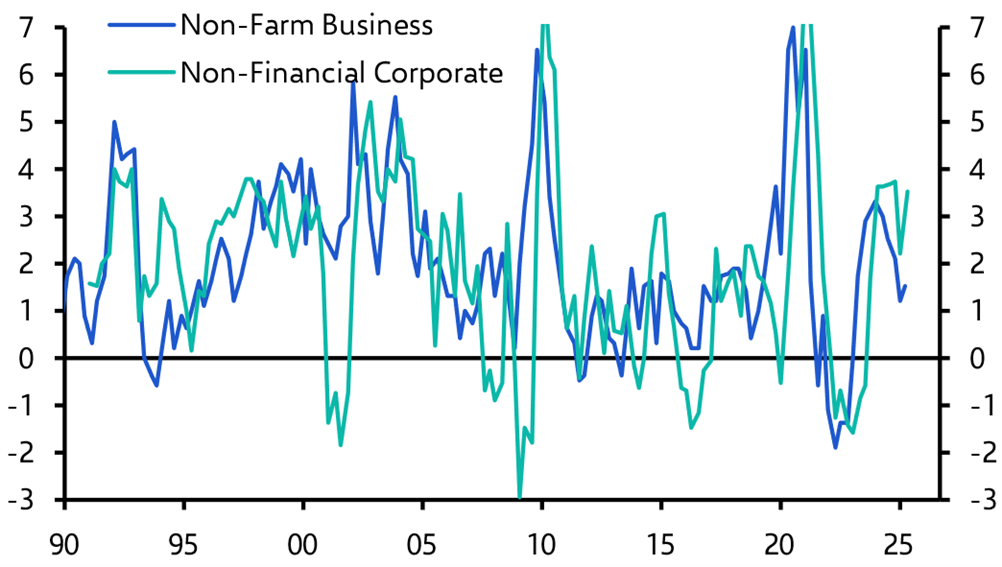

Perhaps more striking is the fact that the economy appears to be growing strongly even as job creation has slowed. The flipside is a marked improvement in productivity. Recent data show productivity in the non-financial corporate sector growing at around 3.5% y/y. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: US Productivity (% y/y) Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

Productivity is almost everything

The drivers of productivity growth are notoriously uncertain and difficult to identify in real time. In a mechanical sense, faster productivity growth is the necessary consequence of employment slowing and GDP growth staying strong. Given the backdrop of heightened policy uncertainty, it is likely that firms are simply working existing employees and capital harder.

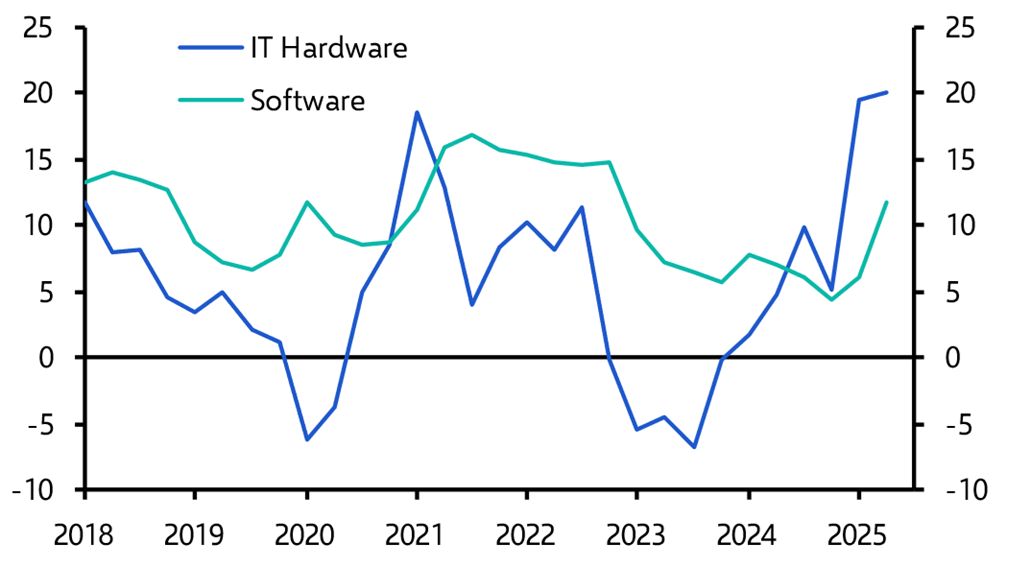

However, at least part of the acceleration in US productivity growth appears linked to a surge in investment in high-tech sectors. Investment in technology hardware is now growing at close to 20% y/y, while software investment is growing at 10% y/y. (See Chart 4.) As our latest US Economic Outlook explains, the counterpart to this investment surge has been a rise in imports of associated inputs, which will have partially offset any boost to GDP. But these may also be the first signs that an AI boom is lifting the US economy.

|

Chart 4: US IT Investment (% y/y) Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

Much now depends on whether the recent surge in productivity and investment can be sustained. While that’s uncertain, it’s worth noting that AI-related investment is still small compared with previous waves of general purpose technologies — and the earnings reports of major tech firms point to capital spending remaining strong in the quarters ahead. Our US Outlook forecasts business investment to rise by 4.7% in 2026 and 5.2% in 2027. (Our US team will have much more to say on the productivity outlook in their Drop-In this Tuesday – register here for that session).

Strikingly, this investment boom has not been replicated in other advanced economies. It therefore speaks directly to America’s distinct capacity to rapidly absorb and scale up new technologies – something that is captured by its leading position in our AI Economic Impact Index (which ranks countries according to their ability to reap the benefits of AI technologies).

In this sense, Trump may be a lucky president: at first sight it seems that a productivity boom is cushioning the drag from his administration’s trade and immigration policies. Whether that luck continues will depend to some extent on whether the boom around AI can be sustained. We tend to side with the techno-optimists on this issue. If that’s the right call, then from the perspective of GDP growth at least, US exceptionalism will survive for a while to come.

In Case You Missed It

The final event in our global series on economic fracturing takes place this Thursday in New York. If you’re in town, come along to hear how the breakdown in US–China relations is reshaping the global system – and meet our team in person. Registration details.

Following its positive recent review of the performance of Italy’s public finances, our Europe team examined whether populists in other major regional economies could/would follow the Meloni playbook.

Senior EM Economist Liam Peach highlighted how relatively low oil prices will further constrain the policy space available to major producers like Saudi Arabia and Russia.