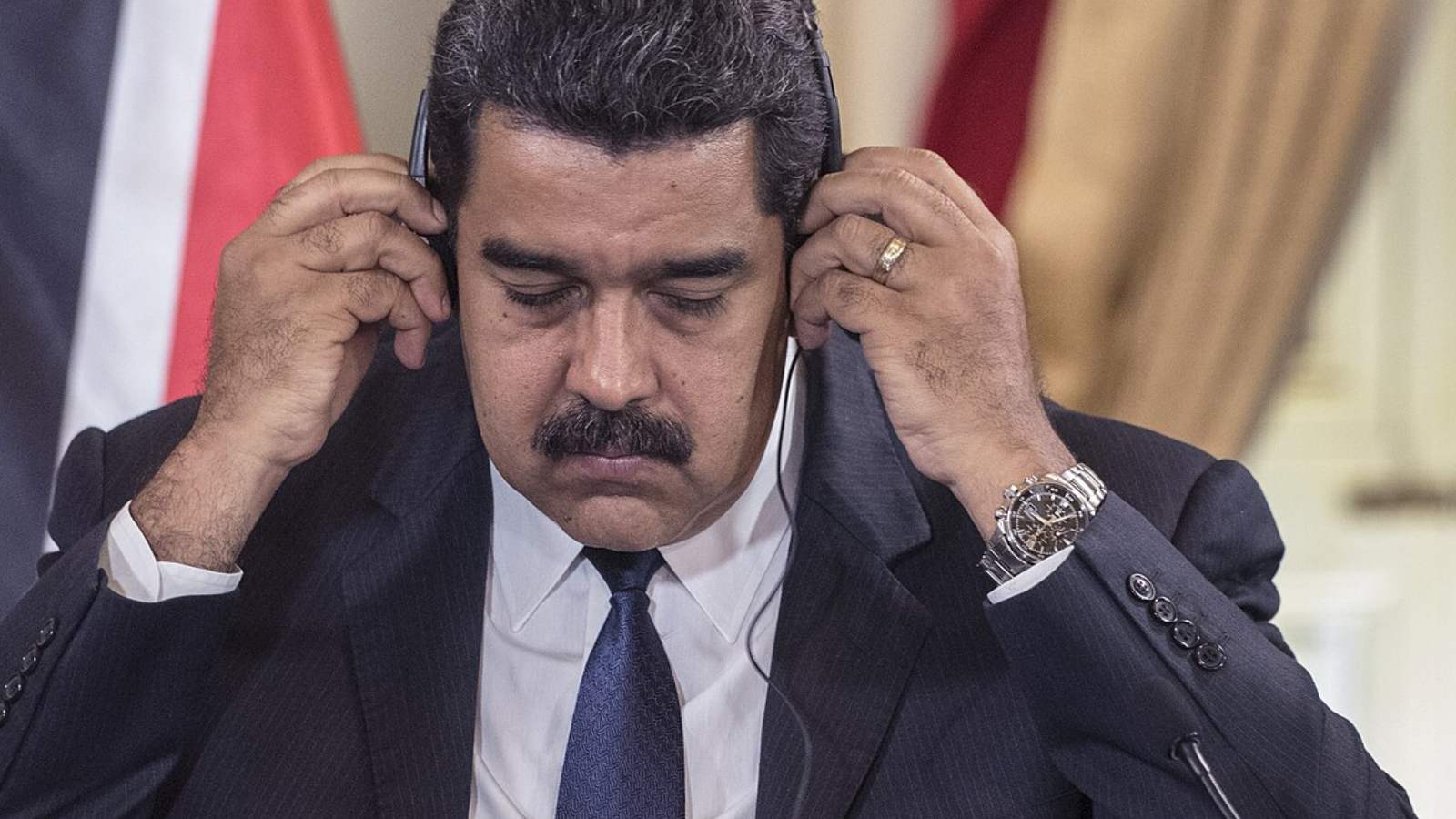

The removal of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro by the US is unlikely to have meaningful near-term economic consequences for the global economy. But its political and geopolitical ramifications will reverberate.

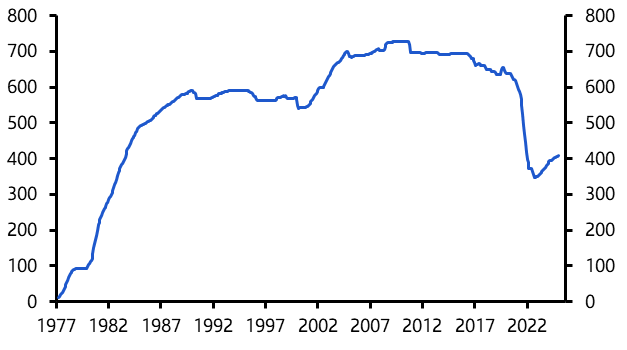

Venezuela’s global economic importance has diminished significantly over the past 50 years. In the 1970s, it accounted for roughly 1% of global GDP and produced around 3.5 million barrels of oil per day (mbpd), or 8% of global supply. Today, it represents barely 0.1% of world GDP and produces about 1mbpd, or just 1% of the global total, making it only the 18th-largest oil producer worldwide. This loss of importance reflects the long, steady collapse of Venezuela’s oil industry, itself the product of decades of economic mismanagement. This mismanagement resulted in hyperinflation, a 70% fall in real GDP and mass emigration in the 2010s – widely considered the worst economic crisis of recent times, outside of warzones.

In theory, Venezuela could again become a major producer: it still claims to hold the world’s largest proven oil reserves. Moreover, comments over the weekend from President Trump suggest that the US intends to play an active role in developing the sector and raising output over coming years.

Venezuelan oil wouldn't move the dial

But theory and reality diverge sharply. If nothing else, geopolitical alignments in Venezuela remain unclear in the wake of Maduro’s capture. But Venezuela’s oil infrastructure has also been heavily degraded by decades of underinvestment and much of Venezuela’s oil is extremely heavy, making it relatively costly to extract and process. Even if production were successfully restored to levels seen a decade ago – around 3 mbpd – this would add only about 2% to global supply. The bigger picture is that rising output in the US and OPEC+ will dominate oil market dynamics over the coming years. We expect global supply growth over the next year or so to push oil prices down towards $50 per barrel.

As things stand, it appears that the US strikes haven’t affected Venezuela’s oil infrastructure. In any case, any short-term disruption to Venezuelan output can easily be offset by increased production elsewhere. And any medium-term recovery in Venezuelan supply would be dwarfed by shifts among the major producers. Speculation that the US might use greater control over Venezuela’s oil industry to reduce dependence on Canadian oil imports runs into the hard realities of scale, geography and infrastructure. Venezuela is simply too small, too distant and too constrained to challenge Canada. In short, we do not believe the weekend’s events will materially alter global oil markets or, by extension, the global economic outlook.

Maduro's capture through the lens of fracturing

Where the consequences will be felt is in politics and geopolitics. The US administration has justified its actions on grounds ranging from combating narco-terrorism to tackling organised crime. These events follow months of US military build-up in the Caribbean and, more recently, pressure on ships transporting Venezuelan oil.

While this can be read as a shift towards a more overtly hemispheric approach to managing geopolitical relations, with the US asserting greater control over developments in its own backyard, it is equally possible to interpret events through the lens of US-China fracturing. Venezuela had become China’s (and Russia’s) most steadfast ally in Latin America, a position that generated unease across the political spectrum in Washington. (For more on China’s presence in Latin America, see here.)

If a more US-aligned administration does ultimately emerge from the weekend’s events, this would represent another major commodity producer edging away from China and back towards the US in our global “fracturing map”. (As we’ve noted here, Saudi Arabia has also moved closer to the US in recent months.)

That said, the manner in which the operation was conducted has unsettled some of America’s traditional allies, particularly in Europe and Canada. We are nonetheless doubtful that this will prove sufficient to push them decisively away from the US camp. We are also sceptical that Europe or Canada will ever become fully independent geopolitical actors or meaningfully align with China.

The countries that are most likely to drift away from the US are those hit hardest by the Trump administration’s aggressive trade policies. India stands out as the most important case. We will be updating our fracturing map in the coming weeks. But while the weekend’s events will have unsettled many US allies, we do not expect them – beyond Venezuela itself – to be truly transformative.

Instead, the ramifications over America’s gunboat diplomacy are likely to be more influential within Latin America. One key flashpoint to watch is whether the same concerns over the drugs trade and organised crime that were used to justify action against Maduro are used to extract concessions from Mexico ahead of the USMCA review later this year – or whether these threats make Mexico less willing to cede ground.