The opening days of 2026 have been a stunning reminder of how far geopolitics has returned as a driver of economic and market narratives.

First came the US operation to seize Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro, forcing greater alignment in Caracas to Washington’s interests while granting US energy firms preferential access to the country’s oil reserves. This was swiftly followed by renewed threats from White House officials to incorporate Greenland into US territory – by force if necessary. All the while, the Trump administration has been pushing for a ceasefire in Ukraine on terms that are widely seen as favourable to Russia, reinforcing the impression that America is loosening its long-standing commitment to Europe.

Sphere we go again

Trump framed Maduro’s capture as a reassertion of the Monroe Doctrine – or the “Donroe Doctrine," in his formulation. It’s a policy named after the fifth president, who first articulated the idea that the Western Hemisphere was a US interest where outside powers should not interfere.

Unsurprisingly, this has helped foster talk about a return to a world divided into ‘spheres of influence’, with the US dominant in the Western Hemisphere, China in Asia and Russia in Europe. Underlying this is a broader retreat of the rules-based international order and the spread of strongman politics.

Donroe doesn’t go

Yet the idea that the world is being carved into spheres of influence shouldn’t be taken too far. Most commentators talk about these spheres in terms of neat, contiguous geographic blocs. If that is correct, and the US is ceding Asia to China and perhaps Europe to Russia, this marks a major retreat. But recent behaviour suggests otherwise.

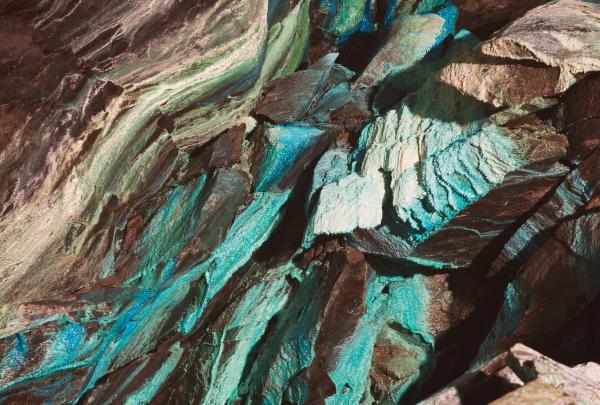

In addition to actions in Venezuela, the US has in the past year conducted military operations in Nigeria, Iran, Yemen, Iraq and Syria. It has stepped up efforts to secure critical minerals in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, including Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In the Philippines, the US is moving ahead with plans to upgrade a naval base on Palawan, a strategically sensitive island facing the South China Sea. It has just agreed to an $11bn arms package for Taiwan. And while the Trump administration’s recent National Security Strategy sharply criticised European allies, it also recommitted the US to “hardening and strengthening” its military presence in the Western Pacific.

In short, it is reasonable to argue that the US is recalibrating its role in Europe and pressing European governments to shoulder more of the security burden there. But Trump’s US still clearly conceives of itself as a global, not merely regional, superpower with interests on every continent. That sits uneasily with the idea of a narrowly hemispheric foreign policy.

Nor is this dynamic confined to the US. China, too, remains active well beyond its immediate neighbourhood, pursuing economic and security interests across Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Latin America. Russia, by contrast, looms large in geopolitical discourse but less so in economic terms: to the extent it has a sphere, it can’t be said to extend far beyond its own borders. Russia’s capacity for disruption is real, but its economic and military weight pales beside that of the US, China – and, collectively, the EU.

Bloc party

We have argued for some time that the way to understand the geopolitical forces that are shaping the global economy is not through the lens of territorially bounded spheres of influence, but rather as a contest between competing global blocs centred on the US and China. Recent events have been consistent with this framework. Both the US and China remain the world’s dominant superpowers, and both have continued to project economic, political and military power far beyond their immediate neighbourhoods. What has changed instead are two important aspects of US strategy in this fractured world.

First, Washington is placing greater emphasis on locking in countries on its immediate doorstep. Trump administration officials are threatening other countries in Latin America beyond Venezuela, while our map of how the world system is fracturing shows geopolitical alignments in the region shifting toward the US. (Note that Saudi Arabia has also moved closer to the US, supporting the idea that Washington continues to project power and build alliances well beyond the Western Hemisphere.)

Second, the US is no longer relying primarily on shared values – democracy, the rule of law, liberal norms – to bind allies together. America’s approach under President Trump has become more overtly transactional and more coercive.

It’s complicated

All of this has important macroeconomic consequences. If the world were genuinely fragmenting into discrete spheres of influence, investors should position for a strengthening of economic, financial and security ties between the US and Latin America and a relative weakening of those ties between the US and Europe and Asia. Similarly, they should expect China to disengage from Latin America and Africa and concentrate its focus on Asia – and for others in Asia, including Japan and Korea, to adapt to a new world with China as the uncontested regional hegemon.

But in a world organised around rival blocs that are shaped by deep social, historical, institutional and technological linkages, economic and financial relationships are likely to remain far more geographically dispersed. The reality is that geopolitical – and economic – relationships are messier than talk of spheres of influence suggests. Wind the clock forward to 2035, and global economic ties are therefore more likely to resemble the pattern shown in our fracturing map than a simple division into regional blocs or spheres.

Related content

Our Markets team weighed news of a DoJ investigation of Jerome Powell against the forces that should support the dollar this year;

David Oxley provided a guide to the potential for Venezuela’s oil sector;

Ariane Curtis analysed how the AI revolution is affecting global trade.