This has been a turbulent past week for the dollar. A sharp sell-off at the start of last week revived the “Sell America” narrative, before the currency partially recovered after Donald Trump nominated Kevin Warsh to be the next Federal Reserve Chair. But fresh questions about the dollar’s future have since been sparked by noises from China suggesting renewed ambitions to push the renminbi and challenge the greenback’s role in the global economy.

The sell-off and the signals from China have together fed into the persistent idea that the dollar’s dominance is coming to an end. They should not. Two very different issues are being conflated: shifts in the value of the dollar over the short term, and potential changes to the dollar’s position at the centre of the global financial system over the medium term.

Warsh vs the dollar

Economists have an unenviable record when it comes to forecasting exchange rates – and for good reason. Currencies are influenced by a shifting mix of economics, politics, market positioning and fiscal and monetary policies, and the relative importance of each can change abruptly. Trying to forecast what comes next should therefore be done with a degree of humility.

That said, we have argued for some time that it is important not to overdo bearishness towards the dollar.

Kevin Warsh, Trump’s nomination to succeed Jerome Powell at the Fed, may not be the “hawkish pick” that some commentators have suggested – it seems implausible that he will not push to lower interest rates once in office, given this was almost certainly a central consideration in choosing him. Even so, Warsh will be only one voice on a 19-member committee, and one of just 12 voting members. Any push for lower rates may also come alongside efforts to reduce the size of the Fed’s balance sheet, thus limiting the overall impact on financial conditions and, by extension, the dollar.

Moreover, Warsh is an orthodox choice in important respects. He has a strong academic background and extensive experience at senior levels within the Federal Reserve system. As a result, fears of a wholesale assault on the Fed’s independence have diminished (as we thought they would). Our base case remains that strong growth and above-target inflation will mean that the Fed delivers just one further 25bp rate cut this year, most likely in June. By contrast, we expect both the Bank of England and the European Central Bank to set policy rates somewhat lower than is currently priced into markets. On this basis, interest-rate differentials should move back in the dollar’s favour, supporting its value.

Not so overvalued

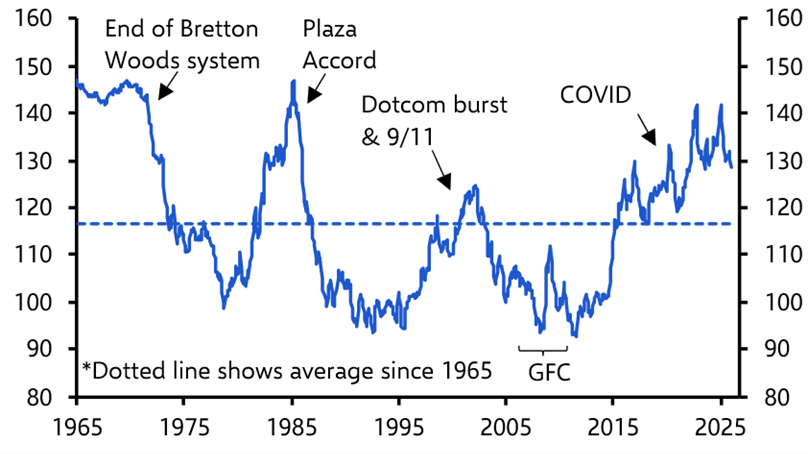

Meanwhile, the dollar looks materially less overvalued than it did a few months ago, and certainly compared with the start of 2025. The real effective exchange rate is now close to its long-run average. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: BIS USD Real Effective Exchange Rate (Jan. 1994 = 100) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

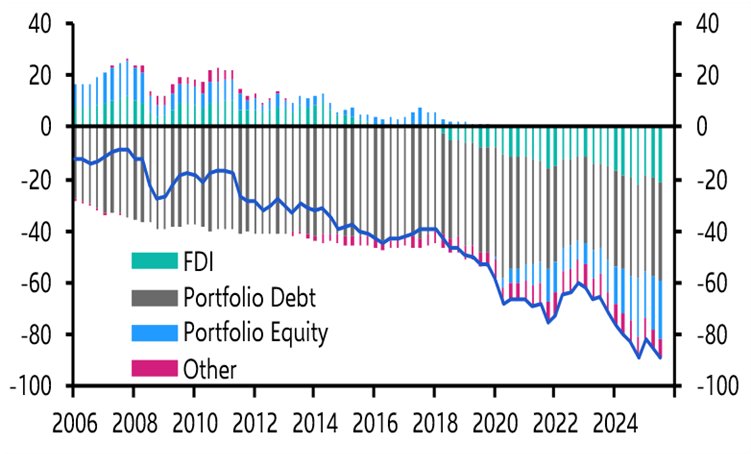

And while the US net international investment position has continued to deteriorate, this largely reflects the strong relative performance of US equity markets. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: US Net International Investment Position (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

Our valuation models suggest the dollar is currently somewhere between fair value and around 5% overvalued. In short, the case for a large, fundamentals-driven adjustment is far weaker than it was a year or so ago.

Of course, currencies can and do overshoot fair value in both directions. The main risk of a more pronounced dollar decline would arise if the administration's words or actions – for example, abandoning America’s long-standing “strong dollar policy” – triggered a further loss of confidence in US institutions and policymaking. That was the basis of the “Sell America” trade around last April’s unveiling of the ‘liberation day’ tariffs.

But pronounced dollar weakness might offer some support to US exports, the principal losers, through higher import prices, would be US consumers. For an administration ostensibly focused on cost-of-living pressures, that would be an odd – and politically risky – choice.

Xi weighs in

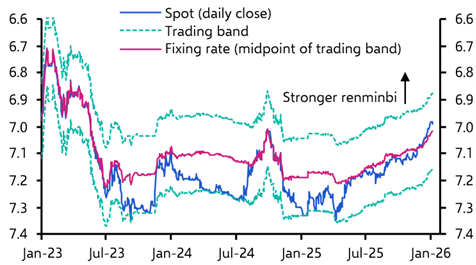

The question of the dollar’s dominant role within the global financial system is quite different. In a weekend article in Qiushi, the Communist Party’s leading ideology journal, Xi Jinping argued that China should build a “powerful currency” that is “widely used in international trade, investment and foreign exchange markets” and which ultimately attains reserve-currency status.

The article was based on comments Xi delivered back in 2024, but the timing of its publication is telling: in plain terms, this is a renewed call to internationalise the renminbi and challenge the dollar’s position at the centre of the global system.

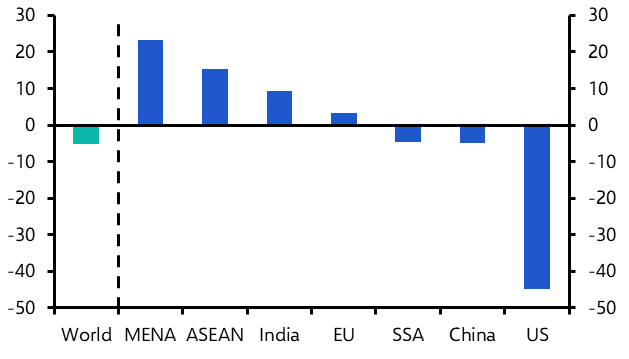

Challenges like these are nothing new. For decades, the dollar has been declared to be living on borrowed time. Yet none of its would-be successors have come close to dislodging it. The reason is simple: the dollar starts from a position of extraordinary strength. Much of the discussion tends to focus on its role as the world’s principal reserve currency. But the dollar’s true power stems from its dominance of global transactions. Around 90% of all foreign-exchange transactions in 2025 involved the dollar, according to the latest triennial survey from the Bank for International Settlements, a share that has remained remarkably stable for roughly four decades.

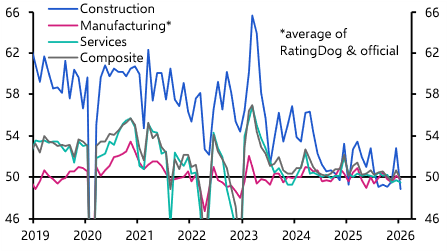

Replacing the dollar would therefore require not just dislodging the incumbent, but the emergence of a credible alternative. At present, none exists. China’s renminbi is the currency of an economy with extensive capital controls and an exceptionally high domestic saving rate – both of which prevent genuine internationalisation. These constraints could be relaxed. But doing so would require far-reaching reforms. Removing capital controls would first necessitate a substantial clean-up of the financial system. And, as we have argued before, reducing China’s saving rate and rebalancing its economy towards consumption is easier said than done. Progress on both fronts is likely to be slow and uneven.

Meanwhile, the dollar continues to benefit from powerful network effects. Trade invoicing, financial contracts, funding markets and hedging instruments are overwhelmingly dollar-based. This entrenched ecosystem makes the dollar cheaper, more liquid and easier to use than any plausible rival, reinforcing its dominance in a self-perpetuating way.

Accurate currency forecasting is fraught with difficulty. But we suspect those betting on further sharp falls in the dollar in the near term – and an end to its global dominance over the medium term – are likely to be disappointed.

Related content

Hamad Hussain argued that the latest run-up in gold prices had all the hallmarks of a speculative bubble as he reiterated our $3500 forecast.

We now believe that the BoJ’s policy rate will climb to 2.5% during the 2030s as inflation settles at higher levels,

The end of China’s “three red lines” policies aimed at cleaning up finances among overleveraged property developers won’t mean the sector now starts to turn around.