Geopolitics has reshaped the world since 2016

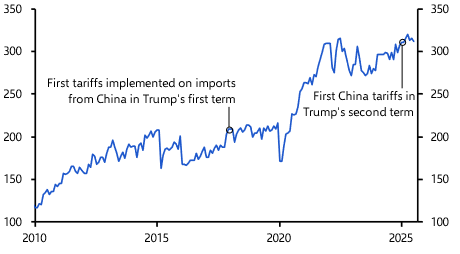

Trump’s first term was defined by a deepening rift with China. By the eve of the pandemic, the US had imposed tariffs on two thirds of Chinese imports and curbed US firms’ dealings with companies such as Huawei and SMIC. Trust collapsed further in Trump’s final year under the shadow of COVID-19.

Another theme was disdain for traditional allies. Trump applied tariffs on Europe, Canada and Japan, and withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The rift with China widened while allies were pushed away.

Biden’s policy fitted more neatly into a paradigm of competition with China involving like-minded countries. His administration kept and expanded tariffs on China, tightened controls on technology, and worked to persuade allies to follow suit. Tariffs on allies were removed, diplomacy emphasised, and “friendshoring” offered as an inducement. Sanctions on Russia, meanwhile, encouraged China to reduce its dependence on the West and boost cross-border use of its currency.

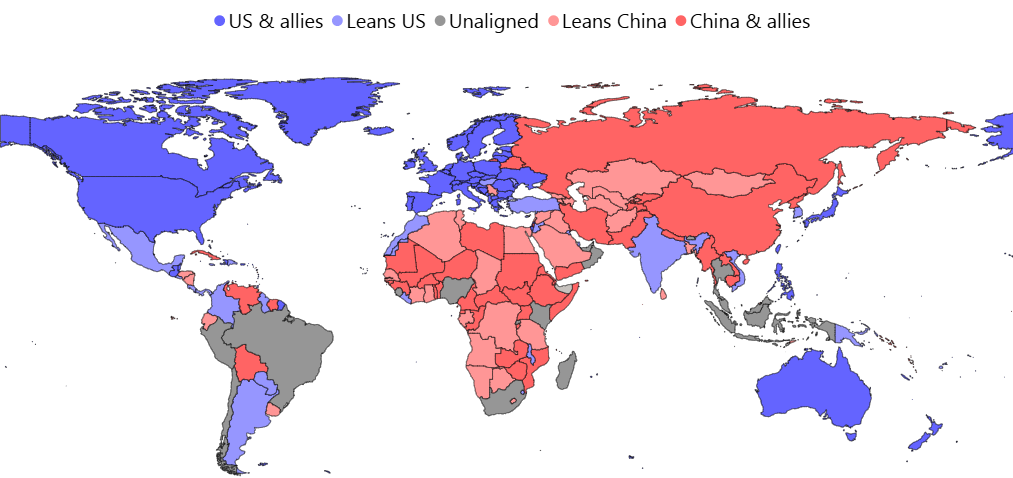

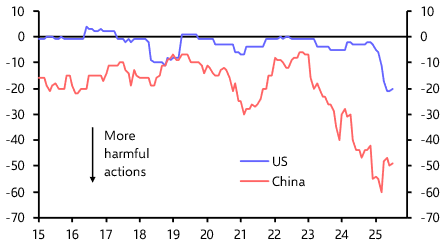

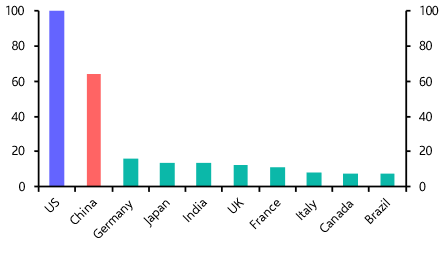

By the end of Biden’s presidency, it made sense to think of the global economy as split into two blocs centred on the US and China. These blocs were shaped not by treaties but by trade, investment, finance, technology and diplomatic ties, with memberships shifting over time.

|

Chart 1: Global alignment towards the US and China at the start of 2025 |

|

|

|

Note: See our Global Fracturing Dashboard for details of how we determine alignment, for further analysis and access to data. |

Our Global Fracturing Dashboard explains how we determine alignments and includes a wealth of interactive analysis that uses these geopolitical blocs to examine global trade flows, the breakdown of industry, financial interactions, UN voting behaviour and more. Eligible clients can download data from the dashboard.

Fracturing in the early days of Trump 2.0

In his first months back in office, Donald Trump has shaken many of the pillars of the global institutional architecture. Before we look at how fracturing might unfold during the remainder of Trump’s second term, it is useful to reflect on what has happened since he returned to office in January.

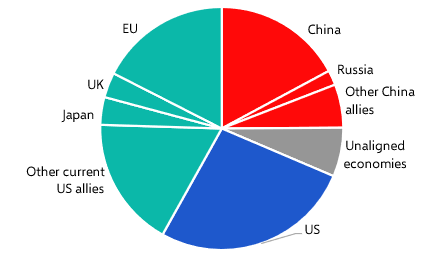

In many respects, the pattern is similar to his first term – relations with traditional US allies have become strained, but decoupling with China has intensified to an even greater degree.

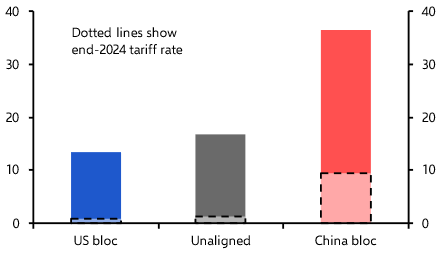

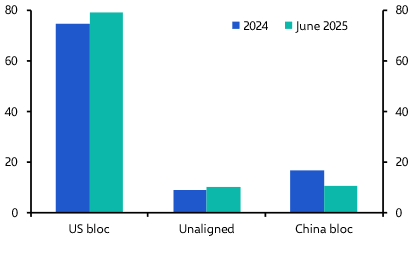

This is most apparent when it comes to trade. Although Trump has hit everyone with tariffs, his administration has come down less heavily on traditional allies like the UK, EU and Japan, and more heavily on China and its allies. (See Chart 2.) Beyond tariffs, the US has taken other steps that appear designed to diminish trade with China. For example, the de minimis tariff exemption for low value packages has been removed – roughly two thirds of affected US imports come from China and Hong Kong. And from October, the US will impose fees for using US ports that only apply to Chinese ships.

|

|

|

|

|

Source: US Census Bureau, Capital Economics Note: Effective tariffs calculated using |

Bilateral trade between the US and China has declined sharply as a result, with the US importing more from its allies and unaligned countries instead. (See Chart 3.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

It is a similar story with capital flows. New US rules now prohibit investment in parts of China’s tech sector, while Trump has threatened to go further under his “America First Investment Policy”. Fewer US companies are entering China, and those already there are more cautious – only 48% of firms surveyed by the US-China Business Council this year planned to invest, down from 80% in 2024.

Flows the other way have also diminished. Since April, China has frozen approvals for greenfield investment and M&A in the US, while continuing to divest gradually from US assets. By contrast, traditional allies are being encouraged to invest more in America, with the launch of a “Known Investor” portal to ease inbound reviews.

Fears that Trump’s approach would push allies towards China have not materialised. Instead, most have accepted trade deals with the US that include pledges to restrict trade and investment with China. The EU, for example, agreed to cooperate on investment reviews and export controls – China not mentioned, but the clear target. Many other deals include commitments to prevent tariff evasion through re-routing trade.

Beyond economics, Trump’s return has caused less rupture than expected. Ties with the EU are strained but intact; NATO and Ukraine support continue; sanctions on Russia remain; and US presence in Asia Pacific is strengthening.

In sum, Trump’s return has brought a more transactional foreign policy and some diplomatic ruptures, but the geopolitical map remains clear: the West, led by the US, on one side, and China (and Russia) on the other.

What will the world look like in four years’ time?

But a lot could change between now and January 2029.

One way to map out possible futures is to focus on different ways in which global economic power could be aligned. Right now, in our view, it makes sense to think of the global economy as comprising two interconnected but distinct blocs in terms of supply chains, access to technology, and financial ties. That’s one model for the future.

Other possibilities are worth considering too: on one side, détente could narrow the gap between the US and China while a true “Grand Bargain” could restore the relationship to the status quo of 2015. The forces that have been pushing the blocs apart would dissipate. Alternatively, there could be significant shifts in the make-up of the two blocs as countries moved sides. Or the two blocs themselves could fracture, creating a truly multipolar world. (See Table 1.) There are different possibilities under each of these headings. Any would materially change the geopolitical picture at the end of the second Trump presidency.

|

Table 1: What could change? |

||

|

US-China |

Movement between |

Multipolar |

|

|

More countries |

|

|

“Phase Two” |

More join China bloc (India, Brazil, SE Asia?) |

… or US allies choose autonomy |

|

Source: Capital Economics |

||

Alternative 1: US-China détente

Trump – unlike most in Washington – does not seem driven by ideology to prevent China’s rise. Some think that leaves space for a deal.

At one end, a wide-ranging “Grand Bargain” could reset relations. Xi would seek US acceptance of China’s “one China principle” on Taiwan. But shifting from the US “one China policy” would destabilise the cross-Strait status quo. Only 7% in Taiwan identify as Chinese, and a US declaration could trigger defiance. If Washington went further and greenlit annexation, dire predictions about economic fallout might not occur – but China hawks argue abandoning Taiwan would cripple US influence in Asia, making this scenario unlikely though not inconceivable.

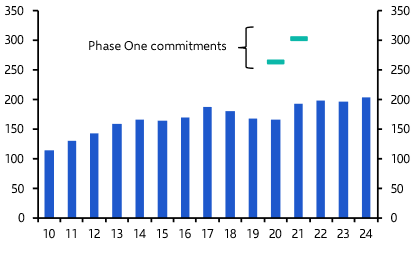

A bargain not involving Taiwan could roll back tariffs and technology restrictions, restoring ties to the early 2010s. That would benefit China most, freeing resources, boosting growth, giving firms access to advanced chips, and easing global pressure to friendshore. In exchange, China might promise large purchases or US investment. But the failure of the Phase One deal would hang over any negotiations. China didn’t follow through on the commitments it made at the start of 2020 to buy more from the US (this failure wasn’t due to the pandemic: China’s pledges were implausible at the time the deal was signed). (See Chart 5.)

And Phase One was an agreement on the US side only to freeze tariffs rather than remove them. A further complication is that tariffs are also, for Trump, a means to raise revenue and create space for tax cuts elsewhere. Close to a third of US tariff revenues in June came from imports from China.

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: BEA, Capital Economics |

In sum, the barriers to the US agreeing a Grand Bargain that could reset the relationship are high. It would require a huge policy shift by the US – a reversal of Trump’s signature tariff policy as well as of the broader containment policies that have been implemented over the past decade. In exchange, the US might receive a pledge of export orders from China and potentially of inward investment plus a promise of secure access to key inputs including rare earths and magnets. None of the US’s concerns about China’s emergence as a geopolitical competitor would be addressed. That’s an underwhelming quid pro quo.

Does China want a reset anyway?

A further constraint on US-China rapprochement would be how willing China was to embrace it. Decoupling has been driven by decisions taken in Beijing as well as in Washington.

China’s leaders would be wary of rebuilding economic linkages in ways that could leave the country vulnerable to a renewed flare-up in tensions with the US down the road. They would also weigh any concessions given to the US against the costs to their wider foreign policy agenda. For example, China’s leadership is probably willing to buy more energy and agricultural goods from the US, given that such purchases can easily be halted again in future. But there is a zero-sum aspect to which countries it buys from. A large-scale shift to buying from the US would require it to significantly scale back purchases from elsewhere, including countries it wants to strengthen ties with, such as Brazil and those in the Gulf. China has been proactively trying to build influence across the emerging world over the past decade, including through the Belt and Road Initiative and won’t abandon those efforts for a pledge of better relations with the US.

Similarly, China’s leadership would be wary of reverting to reliance on high-tech imports. While Chinese officials have publicly disparaged US export controls on high-end chips, they responded to Trump’s recent decision to allow Nvidia to sell its H20 chips to China by discouraging Chinese firms from buying them. It is not lost on China’s leaders that the controls gave a boost to the domestic chip industry and to meeting their self-sufficiency goals that their own industrial policy initiatives had failed to do.

That’s not to say that Chinese officials would oppose a further relaxation of US export controls. But they would likely see it as providing temporary breathing room while they continue to work toward tech self-sufficiency.

Finally, China’s leadership is most likely feeling more confident after the past few months in the country’s ability to cope with high US tariffs if no deal is done. China’s exports are higher than at the start of the year, despite direct exports to the US being substantially lower because exporters have successfully rerouted goods and expanded their market share outside the US. (See Chart 7.) And flexing China’s control over rare earth supply appears to have successfully negated the threat of further large tariff increases.

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: |

Phase Two is possible, a Grand Bargain is not

All this means scope for a substantial reset in US-China relations is limited. A narrower deal, like Phase One, is feasible. That agreement didn’t reset relations but froze tariffs in exchange for Chinese purchases. A Phase Two deal would be doable, and this time China might even secure tariff cuts. Yet even a 20-point reduction would still leave Chinese goods facing tariffs at the high end of those applied to other countries.

China might also face pressure to strengthen the renminbi, but it is unlikely to agree. Many in China see the 1985 Plaza Accord as the moment the US derailed Japan’s rise, and Xi would view any “Mar-a-Lago Accord” as a trap. With China expanding manufacturing and seeking global reliance on its supply chains, a stronger currency would undermine its own strategy.

The bigger picture is that no narrow deal would resolve underlying strains. Xi would not be convinced the US won’t resume efforts to restrain China, nor would Washington hawks trust China’s rise as benign. Firms would assume tariffs and restrictions could return, and both sides would continue to reduce reliance on each other. Even if Trump and Xi struck a détente, it would likely end with Trump’s term. A Phase Two deal would give temporary relief but not alter the deeper geopolitical rift.

Alternative 2: Movement between the blocs

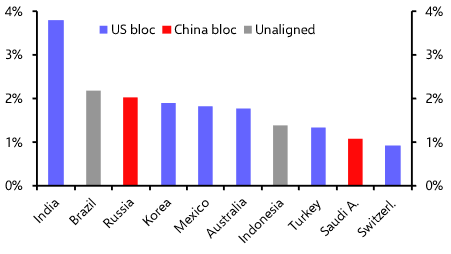

If the geopolitical rivalry between the US and China continues, a second way the balance of global power could be shaken is by some large countries shifting sides. If we assume that the G7 and wider EU are sticking with the US, the next 10 largest economies are those in Chart 8.

|

|

|

|

|

Note: Classifications are drawn from our Global Fracturing Dashboard Sources: |

It is hard to imagine countries like Korea, Mexico, Australia or Switzerland embracing China over the US, but others could. Saudi Arabia has already shifted closer to China, and Indonesia may follow given heavy Chinese investment and US unpopularity – 72% of Indonesians in this year’s ASEAN survey favoured China, double four years ago.

Turkey is unlikely to move given NATO membership and EU ties, while Russia is already China’s “no limits” ally. That leaves Brazil and India. Both face US tariffs – Brazil over Bolsonaro’s trial and tech disputes, India over Russian oil. India offers strategic value as a manufacturing hub and large market, but its tradition of “non-alignment” and closeness to Russia mean its allegiance is uncertain. Modi’s recent visit to China, alongside Putin, underscores that. Brazil, meanwhile, was already in the unaligned camp at the start of the year.

Box 1: Might Russia switch sides?

Some suggest Trump might attempt a “Reverse Nixon” – courting Putin to break Russia’s alliance with China. Russia is by far the largest of China’s close allies, but its loss would matter more strategically than economically: China mainly imports commodities from Russia, while Russia takes just 3% of China’s exports.

Barriers to such a shift are huge. Anti-Western sentiment was entrenched in Russia even before Ukraine, and the war has deepened mistrust and bound Moscow closer to Beijing. The situation is unlike the 1970s, when Mao and Nixon shared a common Soviet adversary. Even if Putin saw value in switching, he could not count on future US administrations, and breaking with Xi for a deal that might not outlast Trump would be risky.

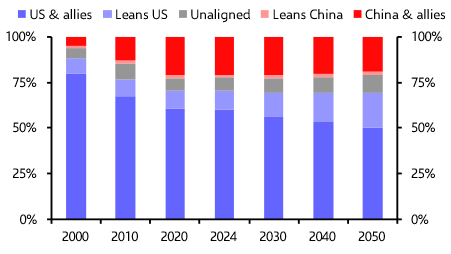

The upshot: bloc realignment is possible, but shifts are more likely towards China than the US. f India, Brazil and Indonesia each joined the China bloc, this would expand the bloc’s size from 22% to 30% of global GDP and lower the US bloc from 71% to 67%. (We classify some countries as unaligned.) In economic terms, the US bloc would still be well over twice as big as the China bloc today. The bigger impact would be felt further ahead: on our current projections, the China bloc’s share of the global economy won’t increase further over the decades ahead as its larger members won’t be growing faster than the global average. (See Chart 9.) The entry into the China bloc of large, relatively-dynamic EMs such as India and Indonesia could change that trajectory.

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: IMF, Capital Economics. Notes: Projections on the basis on country classifications from start of 2025 not changing. Classifications are drawn from our Global Fracturing Dashboard. |

Alternative 3: The blocs break apart

The third possibility is that the world transitions from a bipolar balance to a multipolar alignment. This is something that many leaders profess to want – Presidents Lula, Modi and Macron have each talked about the desirability of a multipolar world in which mid-ranking countries have more autonomy to pursue their interests. Xi and Putin say they are in favour too.

In the most extreme version of a multipolar scenario, the imposition of tariffs by the US leads other countries to impose tariffs not only on the US but on each other, perhaps to protect their domestic industry as global producers compete more aggressively for a share of the non-US market. Barriers go up for investment too. The WTO collapses and other key institutional underpinnings of the US-led global order – NATO, the IMF – are undermined.

A reversal of globalisation that encompassed all major economies would deliver an initial shock to global output and would also result in slower global growth in future.

But such an outcome is not likely. While there has been a pronounced increase in protectionist measures over the past couple of years, these have almost all been implemented either by the US in the form of Trump’s tariffs or against China in response to its surging trade surplus. (See Chart 10.) It was reported in August that Mexico is considering levying tariffs on imports from China too. But the US and China apart, there has been no reversion to tariffs or other forms of trade protection across the rest of the world. In fact, there’s barely been any direct retaliation even against the US.

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: |

US versus the rest

Another way a multipolar world could come into being is through one of the current blocs breaking in two. An increasingly unilateralist US, for example, might push its allies away. If the rest of the current US bloc held together, that would split the world into three blocs of roughly equal economic size, plus a small number of unaligned countries. (See Chart 11.)

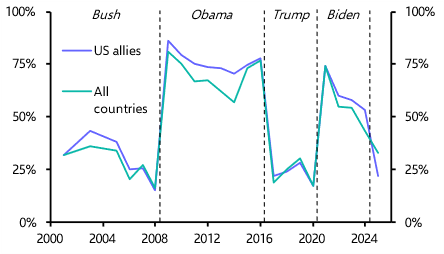

The first few months of Trump’s second term have created obvious strains between the US and traditional allies. A June 2025 survey conducted by Pew Research found a sharp decline in the share of people confident that the US president will “do the right thing” in world affairs. What’s particularly striking is that confidence in the US president is materially lower in countries that we classify as US allies than in the world as a whole. That’s never happened before. (See Chart 12.)

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: |

|

|

|

|

|

Note: Time series shows median country in each group in each year. The definition of US ally follows our Global Fracturing Dashboard. |

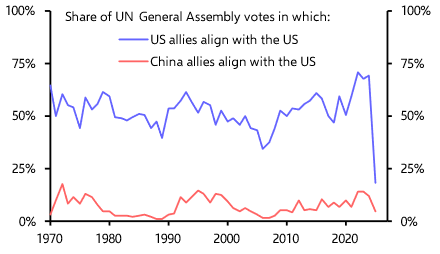

There has been a similar slump in support for the US among traditional allies at the UN General Assembly. In votes in which the US and China have been on opposing sides so far this year, the median US ally has voted alongside the US only 18% of the time, by far the lowest degree of alignment since the People’s Republic took China’s seat at the UN at the end of 1971. (See Chart 13.)

|

|

|

|

|

Note: The share of votes in each year that aligns with the US on issues where China & the US cast opposing votes. Median country. 2025 shows votes up to the end of August. The definition of US and China ally follows our Global Fracturing Dashboard. |

Yet opinion polls and votes only tell us so much. While global public opinion about the US president also declined precipitously during Trump’s first term, it still made sense in 2020 to think of the US and Europe and other allies as constituting a single geopolitical bloc. European governments began to exclude Huawei equipment from telecom networks during this period, the Dutch government started to limit ASML shipments to China and, in 2020, the EU shelved its Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China. And, as discussed above, there’s no sign yet at least that a lack of backing in the UN General Assembly is translating into policy distance from the US on defence or trade policy.

What would it take to create a multipolar world?

Any split of the US or China blocs would require more than shifts in opinion polls and UN votes.

The fissure between the US and China blocs today is reflected in each side’s efforts to secure access to critical inputs, in shifts in supply chains, limits on technology flows, and efforts by China and allies to reduce their dependence on the dollar. Any emerging third bloc would have to be willing to take and withstand similar moves. After all, if the US wanted to prevent sensitive technology, for example, reaching China, it would limit access to that technology for any country that wouldn’t abide by its technology export rules.

If we think of blocs as delineated by supply chains, flows of technology and finance, and by diplomatic links, the splintering of a bloc would involve:

- Firms re-arranging supply chains so that the new bloc can be supplied independently from the rest of the world in strategic sectors.

- Barriers being erected to flows of technology in sensitive areas to and from the new bloc.

- Countries in the new bloc actively trying to reduce their use of dollars (or the renminbi) and reliance on the US (or China’s) financial system.

- The break-up of security groups (NATO, Five Eyes, the Quad, AUKUS, Shanghai Cooperation Organisation).

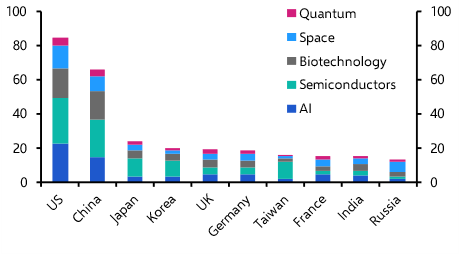

This would be economically disruptive for those leaving. The US and China dwarf the next largest economies in terms of GDP. (See Chart 14.) At market exchange rates, China’s economy is still just two-thirds the size of the US. But it is as big as the next five largest economies combined. The US is second to China in industrial production, but its factories turn out as much as the next seven economies combined.

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: IMF, Capital Economics |

The US and China are similarly dominant as providers of technology. (See Chart 15.) If future economic prosperity and security are perceived to depend on secure access to advanced products and technologies, countries will have little choice but to ally with a country that is able to supply them.

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: “Critical and emerging technologies index”, by E. Rosenbach et al., Belfer Center, Harvard Kennedy School, 2025 |

In practice, this means that the barriers to a country breaking away from both the US and China are substantial.

If the blocs split apart it would hurt both superpowers, particularly the US, whose strength lies in the diversity of its allies. We define fracturing as independent supply chains, tech restrictions and financial decoupling – political frictions alone don’t break blocs as long as these ties hold.

Forces also bind blocs together: integrated supply chains, shared values, and common security concerns. Western sanctions and export controls reflect a broad shift toward seeing Russia and China as threats. Both the US and China also wield coercive powers, such as export controls, financial leverage, and security commitments.

Growth and prosperity in a fractured world

With obstacles blocking the emergence of a multipolar world, and little likelihood that the US-China rift will heal, it still appears most likely that the global economy will be split into two blocs at the end of Donald Trump’s second term. What are the economic implications?

For the detailed view see these pieces on the implications of fracturing for global growth and for inflation. In brief, the impact on productivity and growth depends on two things: how broadly economies seek to decouple (i.e. in narrowly-specified areas, or across the whole relationship), and the speed at which the process evolves. Economies and financial markets in the US bloc should be able to adapt with little disruption to a gradual process of fracturing that was limited to sensitive sectors. The biggest impact will show up in sectors that are targeted rather than in macro variables like GDP. Technology firms, for example, are having to navigate shifting restrictions on trade, investment and their intellectual property.

The China bloc is likely to suffer a more palpable macroeconomic hit from decoupling than the US bloc for three reasons: it is more dependent on the US bloc than vice versa, it is smaller and less diverse, so has fewer options to rebuild supply chains within the bloc, and China is responding by doubling down on an industrial policy approach to lifting self-sufficiency that is further sapping productivity.

As for trade, fracturing will continue to affect supply chains but won’t result in deglobalisation: goods will still be traded widely, but crossing different borders. Large-scale repatriation of production is unlikely.

We don’t expect fracturing to lead to structurally higher inflation. The disinflationary impact of globalisation is often overstated. Studies suggest that globalisation trimmed less than 0.5%-point off annual inflation in advanced economies between the mid-1980s and mid-2000s, taking into account both the direct impact of lower goods prices and the indirect impact through job losses and shifts in wage-setting behaviour. This was a relatively small contribution compared to the broader decline in inflation over that period (it owed more to institutional reforms, like the creation of independent central banks and labour market liberalisation).

What’s more, none of the plausible fracturing scenarios we’ve been talking about imply a wholesale reversal of globalisation. Supply chains may shift but global firms would still be able to source from a range of countries, many of them with low wages. Despite populist ambitions, reshoring on a large scale is unlikely. The impact on migration and labour supply is also likely to be limited.

All this suggests that fracturing is unlikely to drive inflation permanently higher. Instead, we expect greater volatility in inflation outcomes. Globalisation helped expand aggregate global supply. Fracturing fragments supply, especially in strategic sectors, but doesn’t necessarily reduce it. Indeed, fracturing could add to it if countries invest to guarantee access to secure supplies in future. Disruption could cause short-term spikes in prices. But once new suppliers emerge, prices should fall again – perhaps even triggering deflation in specific areas. In other words, inflation will become less predictable, not necessarily higher.

In sum, if fracturing is gradual and targeted:

- The impact on global GDP growth is likely to be modest;

- Trade flows will shift but aggregate world trade will remain broadly stable as a share of global GDP;

- Inflation will be more volatile, but not structurally higher;

- The US bloc is likely to adapt more effectively, aided by the size and economic diversity of aligned economies. China will face a greater challenge.

In this scenario the US is likely to remain the world’s largest economy in market exchange rate terms for the foreseeable future. Likewise, while a greater share of global transactions will be denominated in renminbi, the US dollar will remain the world’s dominant currency and the US will continue to provide the financial plumbing for the world economy.

What looks different now?

The key uncertainty now is whether fracturing will remain gradual and targeted. Donald Trump’s return to the White House has affected both the nature of the fracturing that is underway and the range of possible future paths.

At the end of the Biden administration, the fracturing we were seeing in the West was at the benign end of the scale. Governments in the US, Europe and Japan were all focused on decoupling dependence on China in narrow areas – technology and semiconductors, critical minerals and pharmaceuticals – and they were moving cautiously. The US is now using high tariffs to disincentivise trade across a wide range of sectors. It isn’t clear whether this broad push will narrow again, perhaps as part of a Phase One style trade deal, or whether the Trump administration will push further to try to sever even more US-China economic ties. What’s more, the US is coercing other countries to take a consistent line with it on China. Meanwhile, in using its control of rare earth supplies to put pressure on the West, China has given Western efforts to reduce dependence on China added urgency.

This adds up to a slightly more aggressive form of fracturing than was underway at the start of the year.

That said, as noted above, our analysis suggests that the macroeconomic impact of fracturing is often overstated. We estimate that current policies put the global economy on a path that will result in global GDP ending up 1% lower than it would have been with no fracturing – assuming that is, that the two blocs remain roughly as they are. For comparison, one recent IMF study found that the elimination of all trade between two geopolitical blocs would cost 1.9~7.0% of global GDP (the wide range reflects uncertainty about likely trade elasticities). The central estimate was for a 2.3% loss of global output over the long run.

That’s a reasonable estimate of the scale of the impact of decoupling if it encompassed all trade, not just between the US and China but between the blocs. Lower-income countries, which rely heavily on trade in basic goods and commodities, would be hit hardest. That raises the risk of rising debt distress, social unrest, and food insecurity. A broad-based fracture would hurt everyone. but especially the world’s poorest.

Trump’s return has also raised the prospect that the geopolitical balance could shift in other ways. The three alternative scenarios that we have discussed are shown again in Table 2.

|

Table 2: Economic Consequences of Different Scenarios |

||

|

US-China |

Movement between |

Two blocs |

|

Stronger growth particularly in China |

Positive, at margin, for expanding bloc, negative for contracting bloc |

Significantly negative if bloc loses major members |

|

Probability: low |

Probability: moderate |

Probability: low |

|

Source: Capital Economics |

||

The chances of lasting détente between the US and China seem low. A trade deal along the lines of Phase One is a possibility but it wouldn’t materially affect thinking on either side about the need to decrease exposure in future. If we’re wrong and a deal is agreed that convinces policymakers and businesses that the two countries no longer see each as geopolitical rivals, the economic benefits would mainly accrue to China: it could ease off on the expensive and productivity-sapping industrial policies that it is using to lift self-sufficiency.

The likelihood of the scenario on the right on Table 2 happening – the blocs breaking apart – is also low: there are powerful forces encouraging countries to ally with one of the two superpowers and also making it difficult for them to break away if they wanted to. But the outcome if we’re wrong on this could be highly damaging economically. One extreme would be for every country to put up barriers to all others. We previously estimated that universal 25% tariffs would lower global GDP by 2~3% in the year or two after tariff barriers were erected and reduce subsequent trend growth for the global economy by roughly 0.3% point.

The central of the three scenarios in Table 2 is the most plausible alternative to a continuation of the current geopolitical balance. In this scenario, the world would still be coalescing into two geopolitical blocs but their make-up would differ.

“Defections” matter for the economic outlook in two ways: they reduce the scale of output and size of the market available within the bloc that is shrinking, and they reduce its economic diversity. The more that trade, finance and technology are confined within a bloc, the greater the advantages conferred by size and diversity. The countries that seem most likely to shift position today are in the emerging world and either started the year unaligned in our view (Brazil, South Africa, Indonesia) or saw strategic benefits in leaning towards the US (India). India is most notable here – a realignment towards China than with the US would represent a material shift in the geopolitical balance.

But we shouldn’t overstate the threat to the US bloc of defections if they were to happen on the scale that we’ve argued is plausible, or the gain to China’s bloc. If India, Indonesia and Brazil each joined the China bloc, it would still be much smaller than the US bloc and still suffer from a degree of uniformity. The China bloc’s major members today, China aside, are all primarily commodity producers. The addition of Brazil or Indonesia wouldn’t ease any pressing supply chain, financial or technological constraint. India is different in that it could in principle play the role for Chinese firms that China itself played for global firms in the 1990s and 2000s, of a low cost offshore manufacturing base.

That said, the chances of India aligning with China are still low. The border dispute with China still lingers, while China’s close ties with Pakistan remain a source of concern. India was the one participant in this week’s Shanghai Cooperation Organisation meeting that did not endorse China’s Belt and Road initiative. And India has been more aggressive than any other country in implementing anti-dumping measures against China.

Given China’s dominance of global manufacturing, India almost certainly stands to gain more economically from partnering with the US bloc, presenting itself as a reliable alternative production base. For the time being, US policies may have closed that possibility off. But India is more likely to take an unaligned position than embrace China.