A 25-basis point hike from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) last week was enough to raise hopes in the market that other central banks would soon “pivot” to a more moderate pace of monetary policy tightening before stopping rate increases all together.

The RBA had gone into the meeting with expectations high that it would deliver a fifth 50-bps hike in a row, and its decision to opt for the smaller – more conventional – increase was taken to signal the start of a global shift.

But, as the impact of Friday’s US jobs report made clear, bets that other central banks will soon ease off their campaigns to stamp out inflationary pressure are likely to be lost. The challenges facing policymakers in Australia differ in a number of important respects to those faced by central banks in other advanced economies.

Australia exposed

In the accompanying statement, the RBA made clear that its decision to slow the pace of tightening was motivated by signs that the global economy is slowing. Australia is a more open economy than one such as the US so is more exposed to shifts in global activity. More importantly, however, its major export market is China, where, as I recently noted, the outlook has deteriorated substantially. This may be the first sign that global policymakers are waking up to the severity of the downturn that’s underway in China, but it’s a more clear and present danger for policymakers in Sydney than for those in DC or Frankfurt.

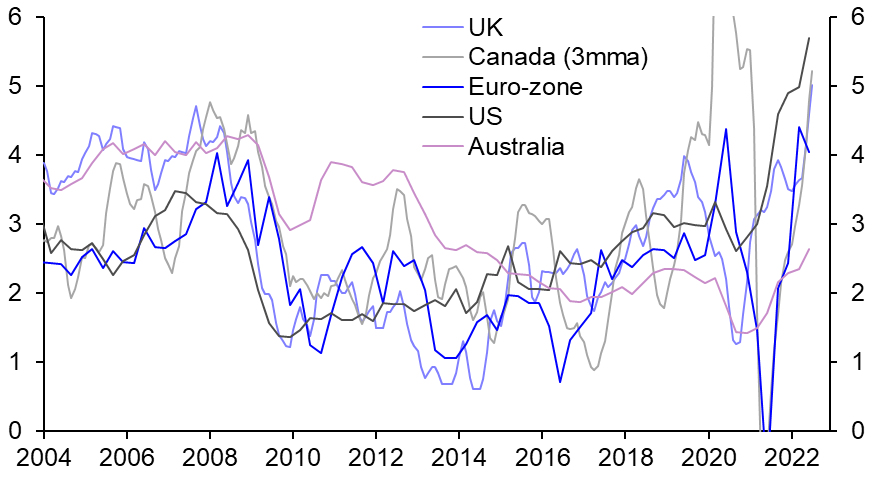

At the same time, domestically-generated inflation pressures in Australia are weaker than in other advanced economies. Services inflation is running at 3.3% in Australia – roughly in line with its 20-year average. But in the US and euro-zone, services inflation is currently double its average rate of the past 20 years. Meanwhile, wage growth in Australia is running at well below the rates seen in the US, euro-zone, Canada or the UK. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Average Earnings (% y/y) |

|

|

|

|

Finally, Australia’s housing market is among the most vulnerable in the developed world to higher interest rates. All central banks need to manage the risks to financial stability as monetary policy is tightened, but housing vulnerabilities mean that the challenge is particularly acute for the RBA. Going into last week’s RBA meeting, we had been forecasting a slowdown in the pace of tightening to 25bps before a hawkish speech by RBA Governor Philip Lowe caused us to increase our forecast to 50bps.

Even so, given Australia’s macro fundamentals and inflation outlook, it was no surprise that the RBA became the first major central bank to downshift from the jumbo 50-100bp hikes which have come to mark this tightening cycle (that isn’t to suggest the RBA will soon stop hiking altogether – we expect 25bp moves in the cash rate at each of the next four meetings to take it to 3.6%.)

Watch the jobs market

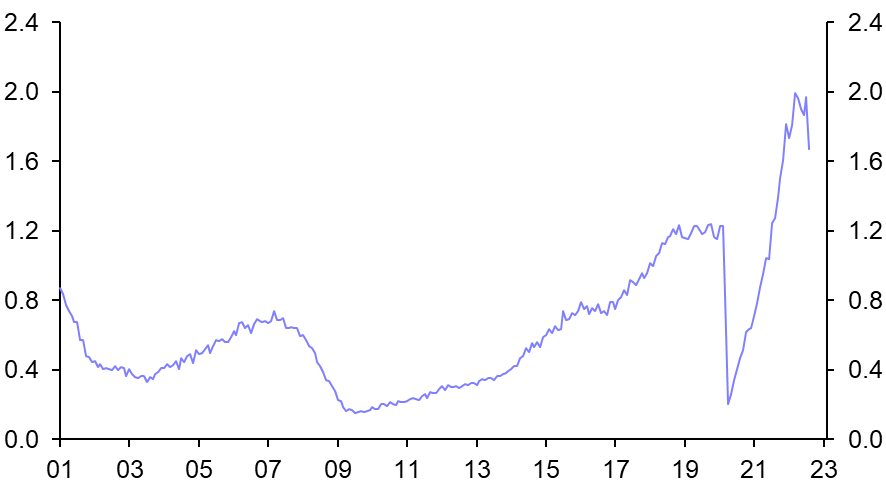

For the Fed and others, the dominant concern remains taming inflation rather than supporting growth. Central to this will be developments in labour markets, which the past week has brought mixed news for US policymakers. On the one hand, the employment report for September, released on Friday, showed a healthy gain in payrolls and a drop in the unemployment rate to just 3.5%. But, data released earlier in the week showed that job openings fell sharply in August. Stepping back from the monthly ebb and flow of data, it’s clear that the US labour market remains extremely tight. The ratio of vacancies to unemployed people remains close to record highs. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: US Vacancy-to-Unemployment Ratio (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

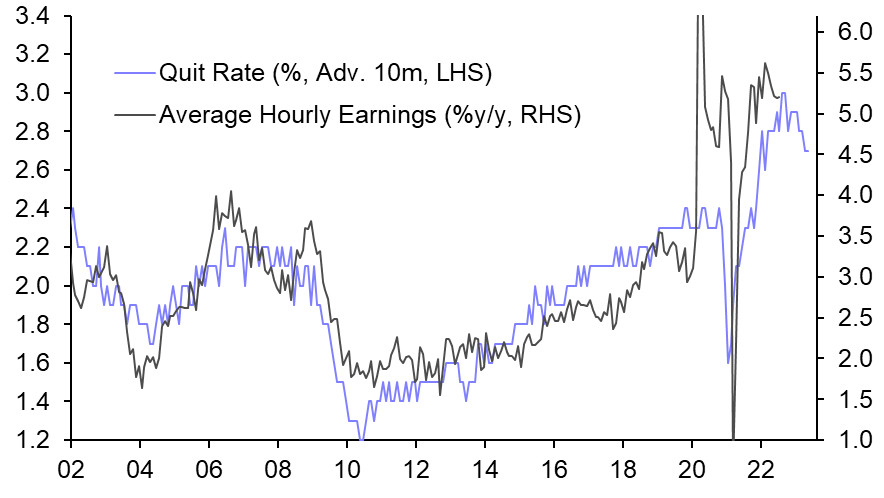

And while the quit rate has dropped over the past six months, it’s still consistent with wage growth of over 4.5%. (See Chart 3.) It’s worth keeping in mind that wage growth needs to slow to below ~3.5% to be consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

|

Chart 3: US Job Quits & Average Hourly Earnings |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

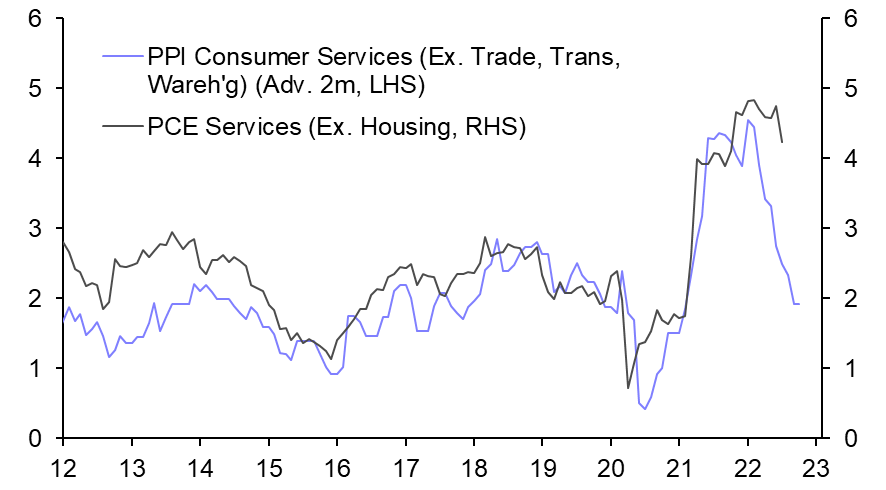

With that said, while conditions remain tight, the fact that job openings and quit rates have turned suggests that some of the heat may be starting to come out of the labour market. Added to that, there are other encouraging signs on inflation bubbling under the surface too. The balance of firms reporting that they are planning to raise prices in the next year has fallen sharply. And the drop in core PPI services inflation is consistent with a sharp decline in PCE services ex-housing inflation over the coming months. (See Chart 4.)

|

Chart 4: US PPI Consumer Services & PCE Services (ex-Housing) (% y/y) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Still waiting for the pivot

The data released over the past week are unlikely to significantly alter the Fed’s view that the labour market is “out of balance”, and US policymakers are likely to maintain a hawkish stance for the next several months.

We expect another 75bps hike in the Fed Funds Rate at next month’s Federal Open Market Committee meeting and ultimately expect it to peak at 4.50-4.75% in this cycle. But the pivot will come: as we outlined in our latest US Economic Outlook, the Fed may slow the pace of tightening to 50bps hikes in December. And, with the economy now set to enter a mild recession early next year, the conditions for a cut in interest rates might be in place towards the end of 2023.

There are few direct implications of last week’s move by the RBA for central banks in the rest of the world, and the focus for the next several months will remain on tightening policy and cooling price pressures. That means further aggressive hikes in interest rates in the US, euro-zone and UK over the coming months.

But the global backdrop is likely to look very different this time next year. In the case of the US, at least, a weaker economy and improving inflation picture may mean that the Fed is able to loosen policy sooner than the markets currently anticipate.

In case you missed it:

- What do US export curbs on semiconductor sales to China mean in the grand scheme? Click here to read our report on global economic fracturing and register for accompanying online events to find out how US-China decoupling, the pandemic and the war in Ukraine have changed the outlook for economies and markets.

- Our Markets team sees even more downside for the S&P 500 as still-elevated earnings expectations adjust to economic reality.

- Vicky Redwood, our Senior Economic Adviser, shows how the new UK government’s dash-for-growth fiscal spending plans may have wound up harming the economy’s long-term outlook.