The fracturing of the global economy is the theme of a major report we’re publishing this week as part of our annual ‘Spotlight’ series of written research and in-person and online presentations.

It’s an attempt to grapple with the question of how the succession of shocks of recent years – the US-China trade war, the pandemic and now the war in Ukraine – will reshape the global economic and financial systems and provide a framework for thinking through this enormously complex issue.

The context is familiar: in the 1990s and 2000s, both policymakers and corporate leaders in major economies had a common purpose of increasing economic and financial integration. But the consensus that this would benefit all started to fray in the wake of the global financial crisis, and manifested itself in the UK’s vote for Brexit and President Trump’s trade wars. Now, concerns about supply chain vulnerabilities, energy security and, above all, growing animosity between China and the West are fanning the flames of economic nationalism. These concerns have been amplified by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

Fracturing – not deglobalising

Our report explores what comes next. One important conclusion is that these strains will not simply result in a rollback of globalisation. Some global links will be severed but others will strengthen. Rather than deglobalising, we think the world economy will coalesce into two blocs centred on the US and on China – a process we’re calling “fracturing”. Whereas the period of globalisation of the 1990s and 2000s was driven by governments and companies working in unison, fracturing is being driven by governments alone.

These developments may mark a significant shift in the global economic landscape, but they might not have a significant impact on the macroeconomic prospects of major advanced economies, all of which are allied with the US. Efforts by governments to secure supply chains for key products and commodities will affect only a small slice of global trade. At the margin, productivity growth will be lower and inflation higher, but any changes will be small and outweighed by other factors. The movement of some high-skilled workers between blocs will slow, but this is a minor part of global migration flows. The US dollar will remain the dominant global currency and the US financial system will continue to provide the financial plumbing for the world economy.

However, the politically-driven nature of fracturing will have a significant impact on the operating environment for US and European firms in those sectors that are most exposed to restrictions on trade, such as technology and pharmaceuticals. And all firms and investors will be operating in a different environment in which geopolitical considerations play a greater role in decisions over the allocation of resources.

In contrast, the impact on productivity growth in China and some of its allies will be substantial. The wider reach of the US-led bloc, and the broader networks within in, will help it to adapt to the challenges posed by fracturing. In contrast, the China-led bloc is dominated by China itself, making adaption harder and therefore increasing the potential economic hit. This is embedded in our view that China’s growth rate will slow to 2% by the end of this decade.

Towards a different global economy

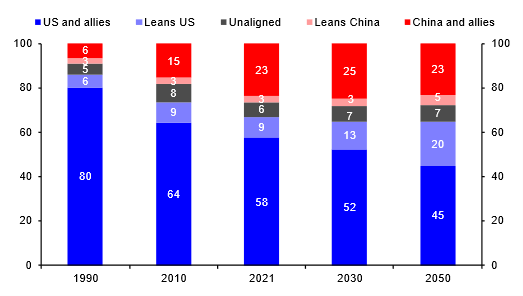

One consequence is that even if not much appears to change for advanced economies, the shape of the world in 2050 could be very different from what many currently suppose. The share of global output accounted for by the China-led bloc has increased sharply over the past three decades, from 10% in 1990 to 25% today. But this surge will peter out over the next few years, in large part due to the productivity-sapping effects of fracturing. The China-led bloc’s weight in the global economy will not increase substantially further. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Shares of Global GDP (%, Market Exchange Rates) |

|

|

|

Sources: Capital Economics |

As long as a crisis is avoided and fracturing leads only to a partial roll-back of prior decades of integration, economies and financial markets will adapt gradually to the new environment. But there are less benign possibilities worth considering too.

One is that the US- and China-centred blocs don’t hold, and that the global economy splinters into smaller regional or national-level groups. This could entail a rise in supply chain nationalism and a broader pushback against the sharing of technology. The loss of economies of scale would result in a larger hit to productivity growth in advanced economies. And a more disruptive shake-up of supply chains could create more volatility in both output and inflation. With that said, a comprehensive splintering of the blocs is unlikely – we think, for example, that ties between the EU and the US will remain fairly strong, even if they become occasionally strained.

A bigger risk is that tensions between the two blocs escalate to confrontation, resulting in a broad severing of economic and financial ties. This would be hugely destabilising: the world’s major economies are now so closely intertwined that even in areas where governments are keen to become more self-reliant – such as semiconductors, batteries, core minerals, and energy – decoupling supply chains will be a lengthy process. An abrupt severing of economic and financial ties would cripple global industry, causing shortages and rampant price rises.

We’ll have more on this later this week. Keep an eye out for the publication of the full report on Thursday but you can register now for the associated events here.

PS

I couldn’t finish this week’s note without commenting on events in the UK. You can find full coverage on our UK service but, having watched the full fiscal car crash evolve from Singapore, where I was visiting clients, I was struck by the lessons for governments elsewhere.

It was not the cuts to National Insurance or corporation tax that got the UK government into this mess. Those were risky, but with careful messaging the fiscal impact should have been manageable. Instead, it was the additional cuts to income tax and the loose talk of more tax cuts to come that spooked the markets – particularly when the government didn’t allow the OBR to publish an assessment of its fiscal plans.

The key lesson for other governments is that they have much less room fiscal error in a world of high inflation and rising interest rates. As we noted last week, perceptions of fiscal sustainability can shift rapidly, and changes to government borrowing costs play a key role in determining the long-run trajectory of the public finances. They have been low and falling for most of the past fifteen years, which has loosened the constraints on governments. That’s no longer the case. As my colleague Andrew Kenningham has noted, populist governments in Europe would do well to pay attention to the unfolding crisis in the UK.

In case you missed it:

- A Plaza Accord 2.0? Jonas Goltermann, who leads our FX coverage, discussed the likelihood, along with other key questions to emerge from his recent Drop-In.

- Thomas Mathews, a Senior Economist on our Markets team, discussed what a Lula victory in Brazil’s presidential election could mean for the country’s financial markets (see our dedicated election page for more coverage of the macro and market implications of Lula vs Bolsonaro).

- Senior Canada Economist Stephen Brown discusses the near and longer-term inflation impact of record immigration – including why we think it will help the Bank of Canada to join the Fed in cutting rates next year.