Global economic officials were in a grim mood at last week’s IMF and World Bank meetings in Washington – and it wasn’t just to do with the presence of the soon-to-be-defenestrated UK Chancellor.

While Kwasi Kwarteng raised hackles among his peers over the unfunded tax cuts that would prove his undoing, mounting official gloom was reflected in a concluding statement warning of a darkening global outlook with risks skewed to the downside.

The IMF may have stopped short of calling a recession, but we are now expecting a mild downturn in the coming quarters, with our forecasts sitting below the consensus. And as a weakening recovery loses further momentum, it’s worth assessing the risks of a much deeper downturn.

If the past two years have taught us anything it is that macroeconomic shocks can appear from leftfield. First, the pandemic produced the sharpest fall in global GDP on record. Then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine created an energy price shock that, for Europe at least, has been larger than the twin oil shocks of the 1970s. It’s possible that the global economy is hit by another “black swan” – an unforeseen but highly consequential event – such as these.

But there are a couple of more visible risks that also threaten to cause a much deeper global downturn involving interest rates and how much and how fast they’ll need to rise in this tightening cycle.

Economic risks from higher rates

The first is that central banks will have to tighten policy more than expected to dampen demand and drive inflation out of the system. Last week’s US CPI shocker has raised the prospect that inflation will be stickier than policymakers had hoped. Another 75-basis-point increase in interest rates is now all but guaranteed at next month’s FOMC meeting, and the risk of a similar move in December has risen.

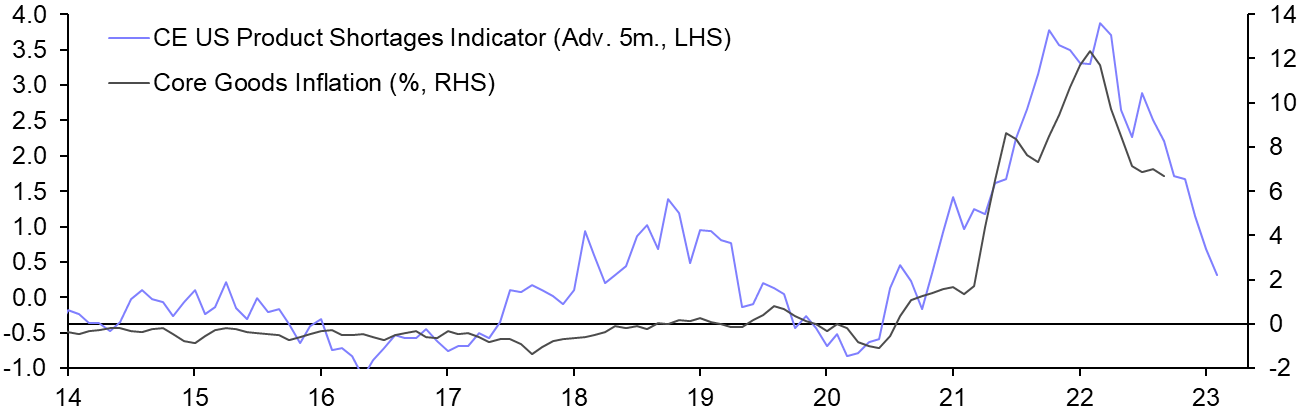

In the wake of the September inflation report, our Senior US Economist Michael Pearce noted that, despite the strength of the data, there are signs of disinflation everywhere else we look. Our proprietary indicator of goods shortages is consistent with core goods inflation dropping to just 2% by Q2 of next year. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Product Shortages & Core Goods CPI Inflation |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics Shortages Indicators |

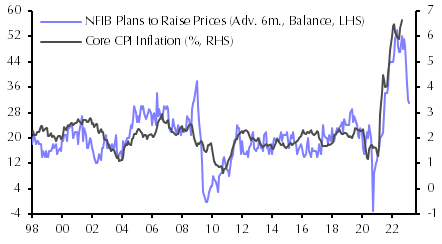

And the number of firms that report they are planning to raise prices over the next 12 months is now consistent with a drop in overall core inflation to 3.5% over the same period. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: US Small Firms' Pricing Plans & Core CPI Inflation |

|

|

| Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Admittedly, the Fed will want to see evidence of weaker price pressures in the actual inflation data before taking much comfort from any of this. And there is so far no sign that the better news on inflation in the US is being replicated in Europe, where underlying price pressures are continuing to build. But the US has led other advanced economies in this inflation cycle, and the outlook is now less troubling than it was only a few months ago.

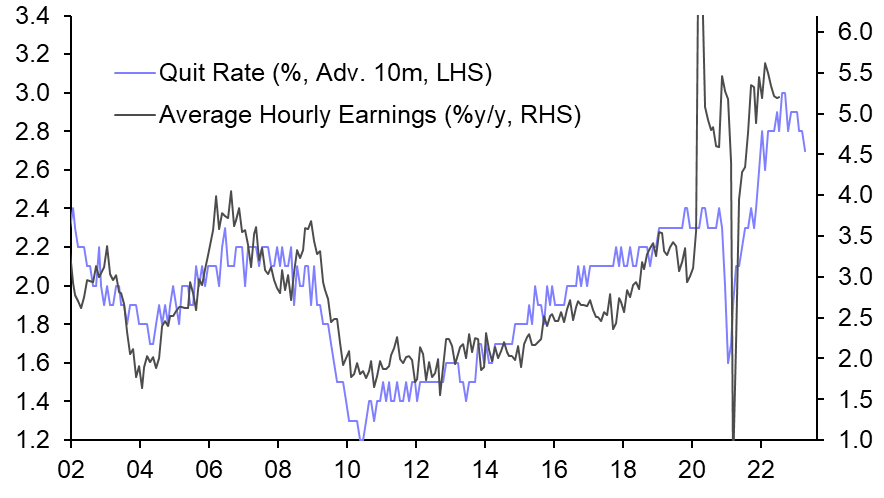

The key thing to watch from here will be what happens in the labour market. The survey data currently point to a slowdown in wage growth to around 4.0-4.5% y/y from 5% by the end of this year. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: Quits & Average Hourly Earnings |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

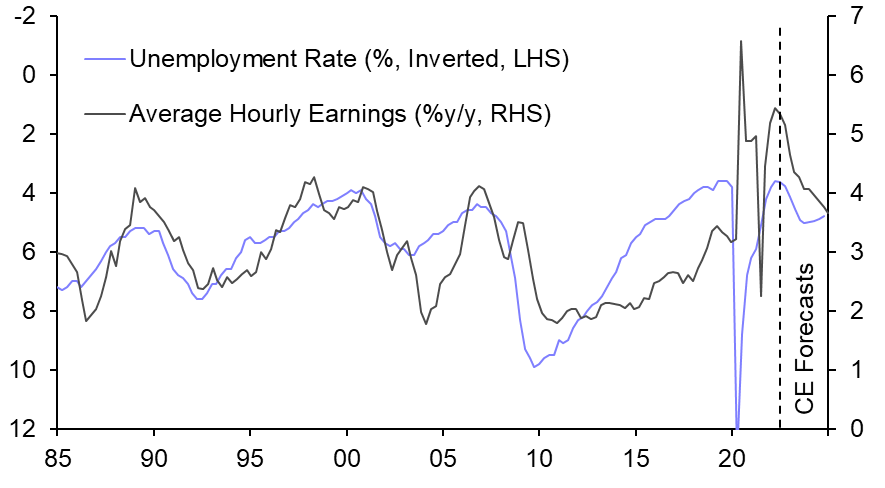

This needs to slow further – ideally to around 3.5-4.0% y/y – in order to be consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target. Our view is that labour market conditions will deteriorate over the coming months, and that a modest rise in the unemployment rate will be sufficient to bring wage growth down to more comfortable levels by the middle of next year. (See Chart 4.)

|

Chart 4: Unemployment & Average Hourly Earnings |

|

|

| Sources: Refinitiv, CE, Federal Reserve |

On this basis, we think the Fed funds rate is likely to peak at 4.50-4.75% in this cycle – broadly in line with what’s currently priced into the market. If we’re wrong, and the Fed has to tighten further in order to drive inflation out of the system, it’s likely to be because persistent labour market tightness keeps wage inflation uncomfortably high.

Financial risks from higher rates

The second potential cause of a deeper downturn is that higher interest rates cause problems in the financial system which then seep into the real economy. The sharp increase in UK gilt yields in recent weeks – and the associated fall in UK asset prices – has been a domestic story but it has invoked global fears of another financial crisis.

We set out a framework for thinking about financial risks in a recent note. The key point is that it’s important to distinguish between problems related to a lack of liquidity and problems related to a lack of solvency. The former are – in relative terms, at least – easy for central banks to extinguish. In most cases it requires them to provide funding to the market as part of their role as lender of last resort. In contrast, the latter are altogether more difficult to manage. This is because solvency crises create losses that must be borne by some part of the financial system. If this happens on a large scale it can impair the entire system of financial intermediation and credit creation, which in turn can cause a sharp contraction in the real economy. Large and systemic solvency crises usually require the government to use its balance sheet to absorb the losses and recapitalise parts of the financial system.

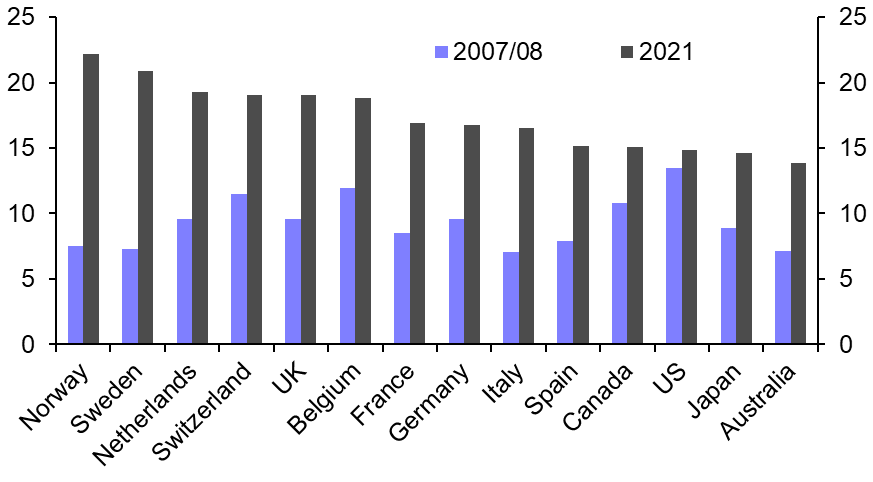

Stricter regulation and monitoring following the global financial crisis mean that commercial banks are now better placed to withstand falls in asset prices and so are less vulnerable to solvency crises. Capital buffers have improved (see Chart 5) and stress tests have been strengthened. Yet sources of financial risk have a habit of materialising in ways that are difficult to fully anticipate in advance.

|

Chart 5: Tier 1 Capital Ratios (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

One new source of risk lies in the shadow banking sector, which provides credit outside of the traditional banking system and is by definition more opaque, lightly regulated and difficult to monitor than plain vanilla banks. In a sign of regulatory nervousness around this, the Bank of England last week warned that mayhem in gilt markets was a reminder of the risks to asset price volatility and market liquidity from non-bank lenders.

Another source of risk lies in the unusual monetary backdrop. Interest rates are not just moving up sharply, but are doing so from extremely low levels. The period of rock-bottom borrowing costs that existed prior to the current tightening cycle was a historical aberration that bid up asset prices across the board. Now that interest rates are rising, there is a corresponding risk of large and simultaneous falls in asset prices. This has the potential to create problems in parts of the financial system that are impossible to foresee in advance.

Indeed, the nightmare situation for central banks is that the level of interest rates that is consistent with bringing inflation back to target proves to be higher than that which is consistent with maintaining financial stability. (This has been explored in more detail in a paper by the New York Fed.)

If problems do emerge, it is likely to be in economies where asset prices – particularly housing – increased substantially during the low-rate era, where the shadow banking sector is relatively large, and where interest rates are now moving up sharply.

As of Monday morning, the Truss government was still scrabbling to restore its credibility with markets following the disastrous mini-Budget. Well it should: a legacy of this whole sorry saga has been has been to lay bare these vulnerabilities in the UK. But officials and investors should be mindful that pockets of these risks exist in all advanced economies

In case you missed it:

- Andrew Hunter, a senior economist on our US team, explained why we think quantitative tightening could end up being smaller in scope than first anticipated.

- Vicky Redwood, our Senior Economic Adviser, asked if we’re sliding towards an era of fiscal dominance.

- Senior China Economist Julian Evans-Pritchard discussed what a reshuffle of China’s most senior economic and finance officials