The Weekly Briefing:

Whatever happened to the China "growth miracle"?

A Capital Economics podcast

19th May, 2023

The cover story of The Economist magazine this past week has been largely based on our long-held view that China’s economic growth would slow to just 2% by the end of this decade, and wouldn’t surpass the US as the world’s biggest economy.

The Capital Economics report outlining this view was first published five years ago this month, and Mark Williams, one of its co-authors, tells David Wilder why the drags on Chinese growth that were highlighted by the China team back in 2018 have only become more pronounced in the intervening years.

Plus, Group Chief Economist Neil Shearing discusses what’s happening in advanced economy housing markets, and why the inflationary surge has helped push through their adjustment from positions of extreme overvaluation.

Finally, Liam Peach from our Emerging Markets explains why the result of first-round voting in Turkey’s presidential election is such a negative for the country’s economic outlook.

Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 19th May and this is your Capital economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, we'll be hearing about the latest on Turkey’s election and revisiting our 2% China growth call, but for now I’m joined by Group Chief Economist Neil Shearing. Hi Neil.

Neil Shearing

Hi David.

David Wilder

We've just had a quieter week after those back-to-back big data releases and central bank announcements and I thought it was worth taking stock – favourite Capital Economics phrase – to look at where we stand versus the challenge of getting inflation back to target. And a big theme that's emerged in the work of the economist team over the past few weeks is what's been going on in housing markets in advanced economies. Specifically, this idea that at least some of them are looking perkier than they did a few months ago. And that's despite this big rise in rates that we've had over the past 18 months. Is there a disconnect there? What's going on housing markets?

Neil Shearing

I think they are a bit of a puzzle at the moment, you're right. We've seen signs of stabilisation in many housing markets. So things like mortgage applications, which had been falling quite sharply, have stabilised across the board – they've rebounded quite a bit in the UK after the debacle of the so-called “mini budget” at the back end of last year. And house prices have been falling in nominal terms, but the pace of declines has slowed in many places. And in Canada, there's actually signs that house prices are picking back up. So signs of stabilisation. But you're right that affordability is still extremely stretched following the hikes in interest rates by central banks over the past 12-18 months. So we think that prices have a bit further to fall from here. We think activity is going to remain extremely weak because what's happening is that there's no force selling so supply is extremely tight, that's given a bit of support to prices, but there's no forced selling so activity levels are, I think, going to remain extremely low.

David Wilder

Can you talk a bit about the impact that inflation has been having on housing markets? To what extent the outlook depends on the outlook for housing markets?

Neil Shearing

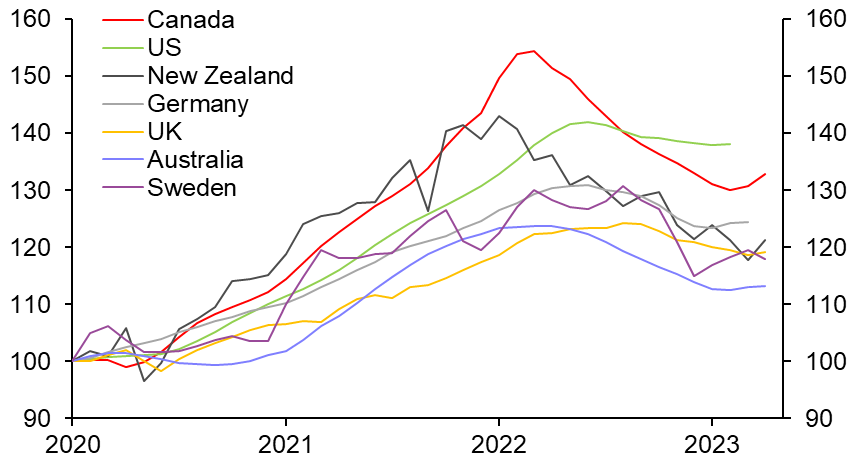

I think that there are two things going on here. One is that the indirect effect of higher inflation on housing markets is that central banks have had to push up interest rates in response to the inflation shock. And of course, that's had an effect on mortgage costs. So we've seen the cost of new mortgages increase sharply across advanced economies. That's not a direct effect of inflation on housing markets, it’s an indirect effect of inflation on housing markets via borrowing costs. And that's what's feeding through into these low levels of mortgage applications, and therefore, sales and activity. I think the second aspect, which has been less remarked upon, but I think is more interesting, and perhaps more significant is the fact that, because prices elsewhere in the economy have been going up by double digit rates, and house prices have generally been either flat or falling in most countries., that means that real highest prices – which is obviously what really matters – have been falling across the board. So we normally see in housing downturns real house prices fall by 20 to 25% historically. Well, because we've had inflation running at 10% or so in most advanced economies and house prices are generally down by kind of 3, 4, 5% in Europe, and more than 10% in Canada and New Zealand, 10% in Sweden, we've seen real house prices fall by in some cases 20 to 25% already. So this is a really good example of how a period of high inflation allows relative prices within an economy to adjust in a way that's less painful than would be the case say if you had to have nominal price falls in housing of 20 25% to get that real, that real house price adjustment of the same magnitude.

David Wilder

Do you think that this is how monetary policymakers are looking at things? Stephen Brown heads our Canada coverage. He's discussed this idea that the Bank of Canada's next move could be another increase in interest rates rather than the cut that we had been expecting. And that's largely because of the housing market’s resilience there. Is that a warning for other central banks?

Neil Shearing

I suspect Canada is a bit of an outlier in this respect. The housing market there is particularly overvalued. When we look across global housing markets, there are signs of stabilisation, as we've discussed, but actually the pickup in sales to new listings, for example, in Canada, it is an outlier. And so I suspect that both the degree of overvaluation to start off with, and the fact that activity appears to be picking up in a more marked way, means that Canada is a bit a bit of an outlier and the Bank of Canada's response will probably be an outlier too. Most central banks obviously, they care about housing markets. We saw in 2008 that if things go wrong in housing markets, they can bring down the banking system and the wider economy. We're not in that situation here though. And in most countries, central banks have focused squarely on inflation. It's the inflation numbers that really matter.

David Wilder

But I guess a core point is that, you know, we've been running the with this idea that most of the pain of monetary policy tightening so far has yet to feed through to the system. And that implies that housing markets have more trouble in store for them as well. And that that will feed through to recessions. And that will knock housing markets as well. So more pain to come, I suppose.

Neil Shearing

Yeah, I think there probably is more pain to come in housing markets, I suspect in nominal terms, prices have further to fall. In real terms they've got further to fall too. Activity is already extremely weak. As we've discussed, there's signs of that stabilising and I don't expect a big rebound in in activity. And if we look across markets, affordability is still extremely stretched. But I think this point about real versus nominal is really interesting, because what it means is that the period of high inflation itself, clearly central banks, think that's a bad thing. They're trying to squeeze that out of the system. And clearly double-digit rates of inflation far into the future would be a bad thing – they would have really detrimental economic effects on things like saving and investment. But there have been some side benefits that I think have so far flown on the radar. And one of those has been to allow relative prices to adjust and in particular, and adjustment in real highest prices that otherwise would have been quite painful has been painful for some still, particularly new borrowers, but rather less painful than they otherwise would have been.

David Wilder

So a lot of the adjustment already there. How does the idea that most of the effects of monetary tightening are still to come, still to feed through, how does that square with the idea that we've had this large adjustment already in real house prices?

Neil Shearing

One part of the answer is that adjustments in asset prices, in housing prices in particular, are only one way in which monetary policy affects the real economy. They're an important way, but they're only one channel through which tighter monetary policy affects the real economy. When we look at other channels, particularly the credit channel, that's where we see more evidence that the effects of tighter policy have yet to fully pass through to lending to the real economy and therefore to activity. I think the other point, too, is that although we have seen some quite large falls in real house prices, in some countries, particularly, like I say, Canada, New Zealand, Sweden, is another, housing markets were extremely overvalued. And they were and they were reliant on extremely low levels of interest rates to maintain those valuations. Now clearly, rates have moved up so that means it's quite a big adjustment in real house prices that's necessary. So, yes, we've seen quite a big adjustment, but that's because quite a big adjustment was needed.

David Wilder

You talked about global financial crisis, I have to ask, if we think that central banks are at or near the end of tightening cycles – and you've spoken about this adjustment in real terms – does that mean that there's now less of a risk of destabilising falls in house prices that would prompt central banks to unwind tightening faster than we would be anticipating?

Neil Shearing

I think most of the risk in that respect is still around the banking system rather than the housing market, per se. When we look across advanced economies, as things stand the market seems pretty convinced the Fed is done with tightening. More mixed messages from central banks in Europe, the Bank of England, the ECB. I suspect, the ECB still has more work to do. The Bank of England may be at the end of its tightening cycle now, but wouldn't rule out one or two more hikes there. In terms of when the cuts come, you're right that if we were to get a big collapse in housing markets, surely that would precipitate some former monetary easing. But I think most of the risks in that regard, are not necessarily in the housing market there in the banking sector, and in particular, what's happening with US regional banks, and the knock on effects onto to credit conditions and lending in the real economy. So far, it looks like there doesn't seem to have been a big passthrough. But as you mentioned earlier, that's partly because most of the effect of monetary tightening so far has yet to really be felt. So I think that's coming. I don't think it's going to be a big destabilising tightening in credit conditions that will force a big reverse by central banks. But I do think that it's still too soon to rule out cuts by the Fed this year as the economy starts to weaken because of tighter credit conditions and labour market starts to soften, and therefore the Fed is ultimately forced to take a step back.

David Wilder

That was Neil Shearing on the housing market-inflation intersection. There's the latest on Turkey’s election still coming up. But first, the cover story of The Economist magazine this past week has been all about whether China is hitting its peak as a share of the global economy. It's based in large part on the formulated by our China team and published almost exactly five years ago in a report called ‘The coming slowdown in China’. Earlier in the week I spoke to Mark Williams, our chief Asia economist and monitor reports co-author’s about how that view looks today. Mark started by explaining the genesis of the team's analysis.

Mark Williams

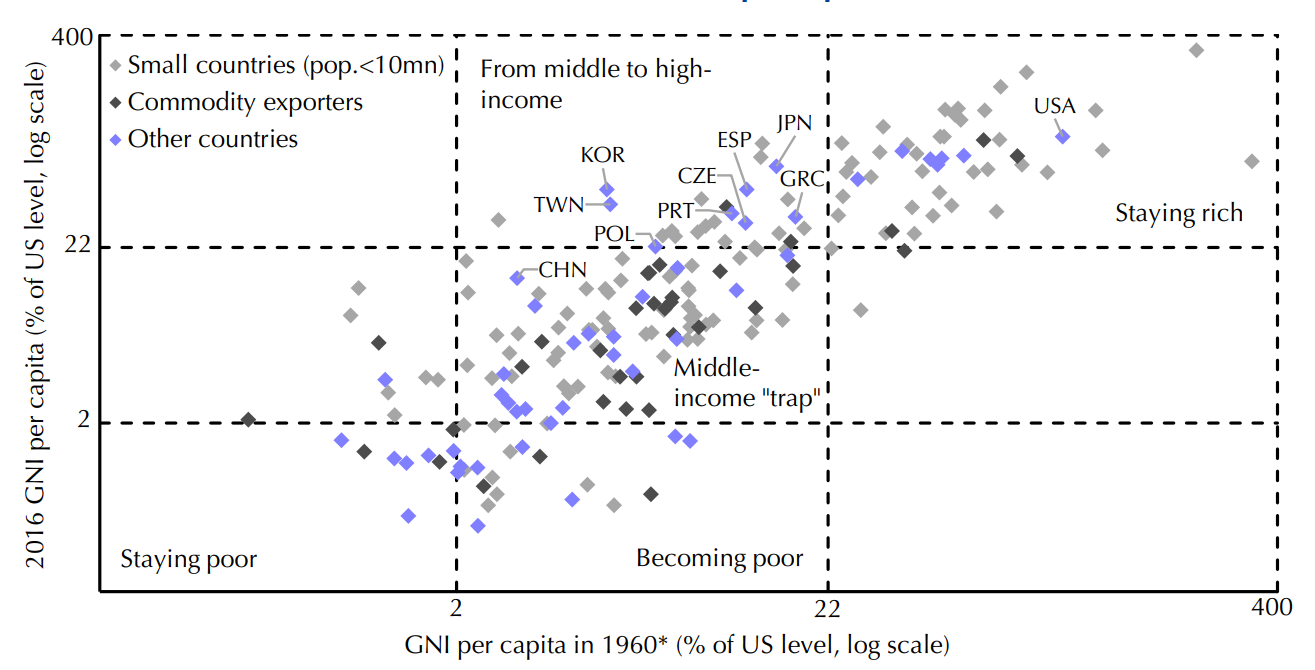

Well, our view at the time was China had been through several years of slowing growth since around 2010. And we saw that the consensus view was that growth was going to recover in a cyclical sense, and then remain very strong into the medium term and further ahead, and we wanted to push back against that, because the developments that we saw in China's economy seemed to point to us to much weaker growth over the medium term and further ahead. And we felt that the slowdown that had happened to that point was not actually a temporary development, but was a trend that would continue. And so then our analysis led us to the conclusion that China would shift from being an outperformer, as it has been within the emerging world or had been within the emerging world for the decades to being essentially a sort of a solid EM, but one that isn't outperforming in any great way. Growth of about 2% was our forecast for 2030.

David Wilder

For a long time, China had been seen as an out performer like other EM Asian economies, -- Korea, Taiwan, are mentioned in the report. Why couldn't it have carried along their path? I know that your original report outlines these structural headwinds, these political drags on the long term economic growth story. Could you could you talk through a couple of those?

Mark Williams

Yes. I mean, one of the big bits of pushback that we got, when we published the report five years ago was to say, look, China has consistently outperformed over a period of decades. And first of all, shouldn't we expect that to continue? It's always the naysayers have always been proved wrong. And secondly, there are other economies that we can see that have succeeded in going from middle to high income, particularly Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and in many ways the argument went, China looks a lot like them. But our argument in 2018, was that those comparisons had already started to really break down. So yes, in many ways, China did resemble these other East Asian success stories. But what they did when they got to middle income in order to lift them to higher income, we said that China would not be able to do. So one of the things that they did was to massively increase their share of global export markets from that point, from middle to higher income. That already didn't seem to be possible for China five years ago: its share of global export markets was already very big, and was already leading to pushback from trading partners.

Our view, therefore, was that it simply couldn't double its share, again, of global export markets as Taiwan created when they were when they were developing. And indeed, I think one way to think about the trade war, which kicked off not that long after we published the report, was that this was a form of pushback from the rest of the world, against China's export prowess. It wasn't going to be able to follow the successful Asian economies in that way.

And then a second way, which is similar sort of argument where the best second way in which China was no longer resembling these economists was that these are all high investment economists, they all just directed a large share of their income into investment every year. But China supercharged that model. China had been investing more than 40% of its income for the decades. And as a result of that China had already, five years ago, 10 years ago, developed a very impressive capital stock. The infrastructure in China was extremely impressive for an emerging economy, it had the highways, the ports, the high speed rail, and so on. Now, that's not a bad thing, you know, that in terms of the quality of life of people in China is a good thing. And the housing stock, for example, in most urban Chinese had decent housing to live in because it had all been built over the previous 20 years. But, if you're thinking about what that means for growth in future, it does mean they can't do that again. So when we looked at the comparison with the rates of investment and the amount of infrastructure and capital stock in the likes of Taiwan, Japan and Korea, when they were at China's stage of development, where they hadn't done quite so much, they could still continue investing a high rates and generating growth for investment in that way whereas we felt that China was sort of running into diminishing returns pretty rapidly. And particularly something like the property sector, we pointed out saying that look, just look at the demographics and China look at the amount of property that's already been built each year, there's no way that this will continue to expand and actually probably over the next 10 or 15 years, the amount of property construction in China would have to fall. So again, since then, obviously, we've had this big property blow up and China property crisis over the past couple of years, which I think is, you know, that process coming to an end.

So in all these different ways, China had resembled these Asian economies in many ways, but it has already gone beyond what they had done – middle income status, and therefore was not able to continue moving rapidly as they had done to get to high income status. There was maybe one thing that China could have done to turn things around at that point, which would have been to liberalise the economy, because that's the other thing that can generate rapid growth is productivity growth. And indeed, when we looked at these other successful Asian economies, they had done that they had stepped back from state intervention in the economy, they’d left a lot more to market forces. So there was a story that possibly China could have followed a road to continued higher growth if it had been willing to step back and much more allow market forces to play their role. But clearly, we could see that under Xi Jinping, that was not the route that China was taking.

David Wilder

Obviously, it's been an eventful five years since you've published the report to say the least. Given how much has happened since you've published, to what extent have events changed your outlook?

Mark Williams

Well as I said, in some ways, a lot has happened over the past five years. So there's been a trade war, there's been a pandemic, which obviously, we couldn't have predicted. And there's been this decoupling, the fracturing of the US-China relationship. Some of those things, I think we obviously we didn't predict exactly the form that these things would take. But I think that in some ways, these are the ways in which the problems that we saw in China's economy five years ago, were manifesting themselves. So this view that China was going to face pushback from the world, and it wouldn't be able to massively further increase its market share and global export markets. I think that the trade war was one example of that sort of pushback. And the decoupling that we're seeing at the moment is a more extreme example of it. I think that is one way in which things maybe have gone further and faster than we might have thought. There has been a dramatic shift in opinion, certainly in the US about relations with China, to a lesser extent elsewhere. But I think still elsewhere, there has been a big shift in sentiment towards China and a new way of thinking about the wisdom of the degree of economic integration there is with China. And in turn that has led to a greater push within China to increase economic self-sufficiency. It's not new, because at the time at the time, we were writing this five years ago the ‘Made in China 2025’ project was already well underway – that started in 2015. So China has been has been trying to increase self-sufficiency across a wide range of industry for a long time. But the attempt to decouple by the US has given that extra impetus. So if anything, then that means that the resulting drag on productivity from greater state intervention in the economy, in my view, is likely to strengthen.

David Wilder

This idea about the Chinese Communist Party and its capacity to adapt in order to survive, are their chances that the leadership will respond to the kind of slowdown that you're forecasting by actually trying to institute those really tough reforms that it's been it's been shying away from for so long?

Mark Williams

Well it's been noticeable this year that the leadership has been trying to sound warmer signals to global investors and telling them that China is open for business and trying to assuage some of their concerns about the business environment in China. So there's certainly on a tactical level, an awareness, I think, of the need to sort of push back against some of the sense that things are getting worse, fast. But fundamentally, you asked whether the the party is able to adapt, but that is fundamentally about making sure that the Party remains powerful, remains in control of key parts of society and the economy. And I think that the decision that was made a long time ago, you know, I think maybe at the time that Xi Jinping took power, maybe before, was that actually, at some point, further economic liberalisation, even if that's what's needed to generate faster growth, could result in undermine undermining the Party's position. So I don't think it's a mistake that they haven't got the right policies. And if only they were able to implement the right policies, things could be okay. I think actually, to some extent that there's a decision that more control is actually needed. And if the cost of that is slower growth then so be it – that’s the cost that China will have to have to pay.

David Wilder

That was Mark Williams on our long term China outlook. And finally, this week first round voting in Turkey's presidential election, so incumbent Reccep Tayep Erdogan do surprisingly well against challenger Kemal Kilicdaroglu. That makes an Erdogan victory in second round voting at the end of this month, a real possibility and as Senior EM economist Liam peach explains, there's good reasons why markets aren't happy with that prospect.

Liam Peach

The election result on Sunday was all about Erdogan really. He didn't gain the 50% vote share needed to win, but he performed much better than expected and the polls that were pointing to perhaps a Kilicdaroglu win in the first round didn't materialise. The market response has generally been quite negative. The stock market on Monday fell by 6%. It has stabilised a bit since then, but in general, we've seen a lot of weakness in Turkish equities, Turkey's sovereign CDS premia, which is the price to protect against sovereign default has increased quite sharply. It's not at a level that we saw in Turkey in 2022. But it has increased quite sharply. And I think that's investors now pricing in the potential for perhaps quite a big financial crisis in in Turkey under Erdogan, particularly if some of the distortive policies that have taken place over the past year or so remain. There hasn't been a big reaction in Turkey's currency market. On Monday, the lira fell by half a percent against the dollar. It's continued to weaken a little bit since then. But in general, the moves have been quite small. I think that that largely reflects the intervention and the FX restrictions that the central bank have put in place to stem the depreciation of the currency. So we haven't really seen a big impact there. It's been mostly in other parts of Turkey's financial markets. But I think in general, quite a bad outcome for investors, particularly those investors that were looking for an opposition victory and a return to orthodox policymaking.

David Wilder

Which part of the economy do you think a crisis is most likely to emerge in? And how long before we do see a real blow up like crise past?

Liam Peach

I think everyone is looking at the currency. Now, the Turkish lira has been heavily managed for quite some time. The Turkish authorities have intervened quite a lot over the past year, and they've put in place these quite restrictive lira-ization policies to manage the currency. I think everybody now is in agreement that the lira will need to fall. After 28th May. I think the question is how quickly does the lira align with its fundamentals? You know, the lira is currently trading at 19.7 against the dollar. We think by the end of this year, it's probably going to end around 26 to the dollar – so quite a big depreciation. Again, it depends on how quickly we get there. I think policymakers will want to loosen their grip on the currency over the coming months. But I think there's this risk in Turkey now that policymakers tried to manage the lira with the current policy framework for too long, maybe for as long as they can no longer hold on to it. So that's the risk. I think the risk is that we do see destabilising falls at some point in the future. Destabilising falls in the Turkish lira would cause foreign currency strains across the economy, including in the banking sector, and spilling over into the sovereign debt position. I think all of this would create a lot of macro instability in Turkey. And I think that's the big risk that investors are really worried about. It could be this year, it could be in a couple of years. But I think it's the risk that's on the agenda.

David Wilder

And is there a chance to the new Erdogan administration would roll back any of these unorthodox policies that have caused so much damage to the economy?

Liam Peach

There is a there is a very small probability that Turkey now goes back to an orthodox policy environment, but we think it is on balance quite a small probability. I think Erdogan really disagrees with the idea of raising interest rates. I think it's so ingrained in his idea and management of macroeconomic policy that interest rate hikes, we think, are off the table. If Turkey were to experience quite destabilising currency falls, and we think ultimately, we think there could be a lurch towards more strict capital controls, which could even be greater restrictions on foreign currency in the private sector, for example, and import and export flows. So I think that's probably where Turkey is going to go. With interest rates off the cards, I think a lot of the pressures are really going to build. We're going to see a continuation of these macroeconomic imbalances. It's going to involve really high inflation, really, really low real interest rates and balance of payment strains.

David Wilder

That's it for this week, you can find all our work on inflation, housing, Turkey, China, and much more on our website capitaleconomics.com. For the complete experience, including data and charting tools and direct economist access, check out CE Advance, our premium platform. Don't forget to subscribe to this podcast via Spotify, Apple or wherever you listen. But until next week, goodbye.