The Weekly Briefing:

How worried should we be about the debt ceiling?

A Capital Economics podcast

12th May, 2023

The White House and congressional leaders are still working to try to reach agreement on raising the debt ceiling, but there’s no guarantee that a deal will get done in time. Deputy Chief US Economist Andrew Hunter and Deputy Chief Markets Economist Jonas Goltermann speak to David Wilder about this latest flare-up over the debt ceiling, including the most likely outcome, the potential for a default, why minting a trillion dollar coin wouldn’t work and what’s really going on in the CDS market.

Plus, Group Chief Economist Neil Shearing addresses some of the big themes that have come out of a series of client roundtables in Asia, including whether China’s economic recovery is already over, why core inflation data look so troubling and what’s wrong with the idea of a BRICS currency.

Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 12th May and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, we'll be hearing all about the latest debt ceiling saga in the US and potential market fallout. But now I'm joined by Group Chief Economist Neil Shearing. Hi, Neil.

Neil Shearing

Hi, David.

David Wilder

We've been talking about the roundtables that we've been holding for clients in Hong Kong and Singapore this past week, and some of the questions and themes that continued to come up out of those sessions. Obviously, the China outlook was a pretty consistent theme there. We’ve had the strong Q1 data that grabbed headlines last month. But in this past week, we've seen some disappointing trade data and some pretty ugly credit numbers. Is the China recovery already over?

Neil Shearing

Well, the data over the past week or so certainly suggests that the best of the recovery is now behind us. We've been following some of the high frequency data very closely, in particular, the data on spending over the Labour Day holiday week at the start of this month – that actually suggests that domestic spending was pretty strong over the holiday period. The consequence of that, though, is that if you looked at where spending in large retail and catering establishments now is in China, it's pretty much back to its pre-COVID trends. So that suggests to us at least that most of this rebound from the lifting of zero-COVID restrictions is now in the rearview mirror. Roll the clock forward, what does it mean? I think you get to the second half of the year I don't think we're gonna see the Chinese economy collapse. And yes, the credit data were certainly softer than we had anticipated. But I don't think we're gonna see a collapse in the Chinese economy. What we're going to see is a slowdown to a more normal pace of growth. On our estimates, the economy expanded by about 7% q/q in the first quarter of this year – that's on our China activity proxy measure – clearly that's unsustainable. That reflects the rebound from the lifting of zero-COVID restrictions. As we shift to the second half of this year, we're going to see a slowdown to a more normal rate of expansion in China, say 1% a quarter, something like that. And I think that's going to be the direction of travel over the coming months and quarters.

David Wilder

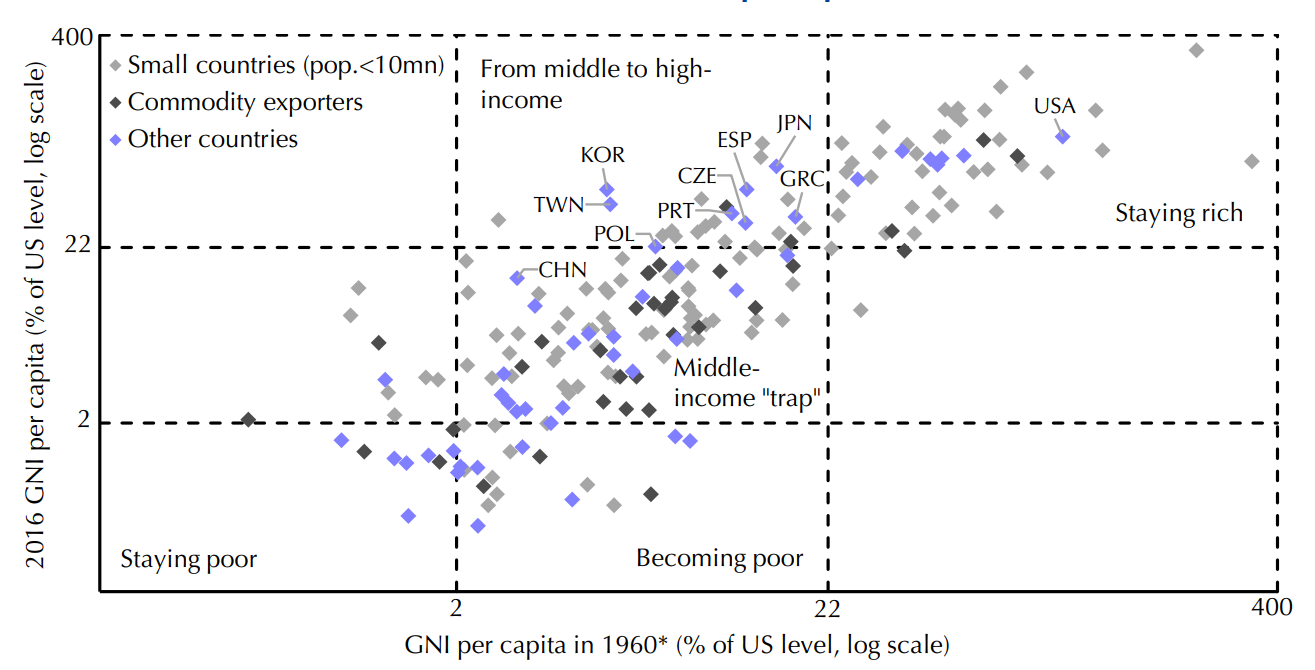

What about further out? The cover story of The Economist magazine this week draws on analysis done in 2018 by Mark Williams and Julian Evans-Pritchard from our China team, which makes the case for its economy growing at just 2% by the end of this decade. At the time, that was pretty much heresy wasn't? The expectations were still mostly that the economy would continue growing in the high single digits as it had for previous decades. Can you walk us through Mark and Julian's analysis?

Neil Shearing

Yeah, well, like you say, the report that Mark and Julian published five years ago, set out this view that China's economy would ultimately slow to a growth rate of about 2%. By the start of the 2030s. Obviously, a lot has changed in the intervening period: we’ve had a pandemic; we've had crackdowns on various sectors in China's economy; we've had a deterioration in the relationship between the US and China over that period, too. But I think a lot of the analysis in that piece still stands up. That piece flagged many of the challenges that have become more prominent over the past couple of years: the constraints on investments; the problems with this high savings high investment model; problems in the property sector; pushback from trading partners, including the US; the demographic outlook, which is increasingly difficult – China's working age population and the population as a whole are starting to shrink. And most importantly, the fact that policymaking in China is becoming more centralized – there’s greater control from the centre over the allocation of resource both capital and labour within the economy. And China is at the point of its development, where the market needs to do more work in terms of allocating resource. So that's the central issue. It's the fact that there's been this push by Xi to reassert the primacy of the party, reassert control over the economy, and that's exactly what China's economy doesn't need at this stage of development. Put that together with all these lingering structural issues, demographic challenges, we get to a 2% growth view. But as you say, that was heresy five years ago. It doesn't look quite so out there now,

David Wilder

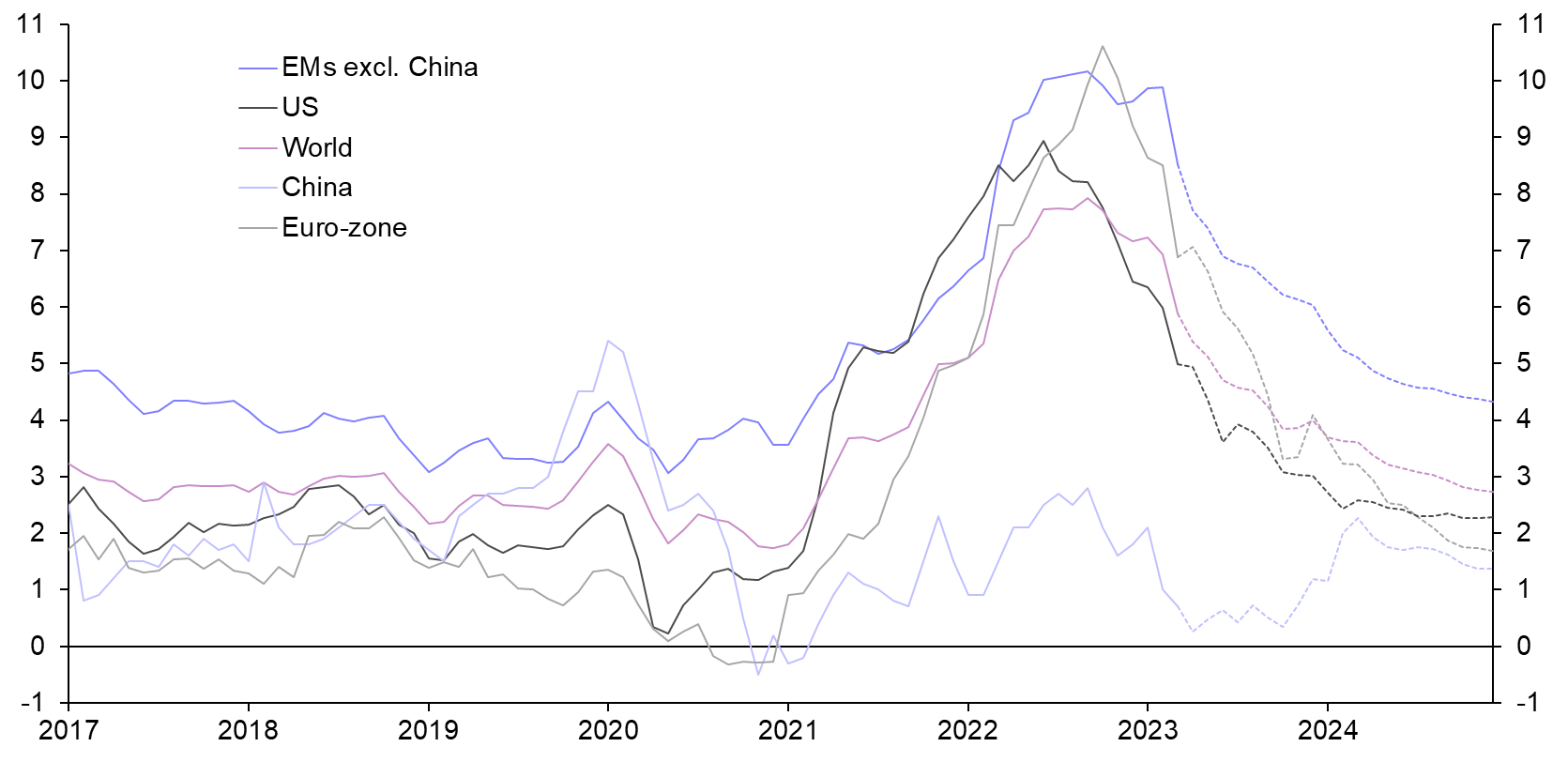

And moving away from China but going back to these Asia meetings with clients a lot of questions about inflation. Not so much to do with what's happening in Asia, per se but what's been happening in western economies. We've had new inflation data from the US in the past few days, but also from Norway, for example. The message hasn't been that encouraging. How big is the risk that core inflation remains high? And does that mean that banks like the Fed and the Bank of England are gonna have to do more even though we're now thinking they're either at or near the end of their tightening cycles? Yes

Neil Shearing

Yes you’re right the data released over the past couple of weeks on inflation has not been particularly encouraging for central banks. Now, headline inflation fell in the euro-zone but core inflation edged up. And then in the past few days, we've had the news from the US that core inflation again, another 0.4% month over month increase in April. So food and energy shocks across developed economies appear to be easing – inflation there's coming down – but core inflation is proving to be extremely sticky. And in the US actually is interesting that we've had core goods inflation having eased substantially over the past couple of quarters but then it edged up again last month driven in part by a big increase in used vehicle prices. I think most troubling for policymakers, though, is what's happening in the services sector. Core services inflation, there's no signs really that that's starting to ease at the moment. And we know the policymakers are putting quite a lot of emphasis on services inflation because that's where you're most likely to see, I think, the pass through from wage growth into domestic services inflation. So troubling picture for central banks still. Now the Fed has signalled that it's probably done with tightening, the Bank of England was more equivocal when it met in the past week. Our sense is that it’s probably at the end of its tightening cycle but we wouldn't rule out another hike or two. The ECB thinks it has more work to do. We've got rates there going to 3.75% at a peak for the end of this year. So central banks certainly in Europe with a bit more work to do, I think. In the US, the key is going to be the labour market. The JOLTS data, the job openings data appear to be pointing to a slowdown in wage growth, the Atlanta Fed wage tracker is starting to come down. I think the Fed’s going to pay very, very close attention to how those data evolve over the coming months.

David Wilder

The last few big themes that came out of our meetings that I wanted to put to you was about the future of the dollar, including this idea of a BRICS currency that has been doing the rounds for a while – this idea that Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa could challenge US dollar dominance with a common currency plan. It seems to be serious enough that it's on the agenda for the BRICS meeting in Johannesburg in late summer. I know you've talked and written extensively about why talk of the dollar’s demise is greatly exaggerated. Is a BRICS currency just more of this sort of wishful thinking on the part of adversaries of the US dollar?

Neil Shearing

Well I think it's all very well and good talking about a BRICS currency. It’s far more difficult to actually do something about it, particularly on a scale that's going to rival the dollar’s role in the global financial system for all the reasons that we've set out in previous research and indeed, we've talked about on this podcast. When it comes to bricks currency itself, it's unclear actually what the various leaders of the BRICS economies are actually talking about. Indeed, whether they're talking about the same thing when they talk about BRICS currencies. I think more fundamentally, when you think about the role of the dollar, whether it’s the reniminbi, a BRICScoin or any other currency for that matter might challenge it in the global financial system. A lot of focus tends to fall on the role of the dollar as a reserve currency, a country's holding dollars in reserve in their central bank reserves. I think actually, that misunderstands why the dollar is so important – it's not about the use of dollars in reserves, it's about the use of dollars in cross-border transactions. And if you look at data from the BIS over the past three decades or so, the share of cross border transactions denominated in dollars has not shifted, it's remained extremely high. And the reason for that fundamentally is a lack of credible alternatives and these huge network effects that build up around the dollar as a result of this dominance in cross border transactions. So roll the clock forward, I suspect the renminbi, potentially a BRICcoin, might get used more use in cross border transactions. The share of these currencies being used in cross border transactions will increase I suspect over the coming years, but it's not going to increase on the scale that's likely to threaten the dollar.

David Wilder

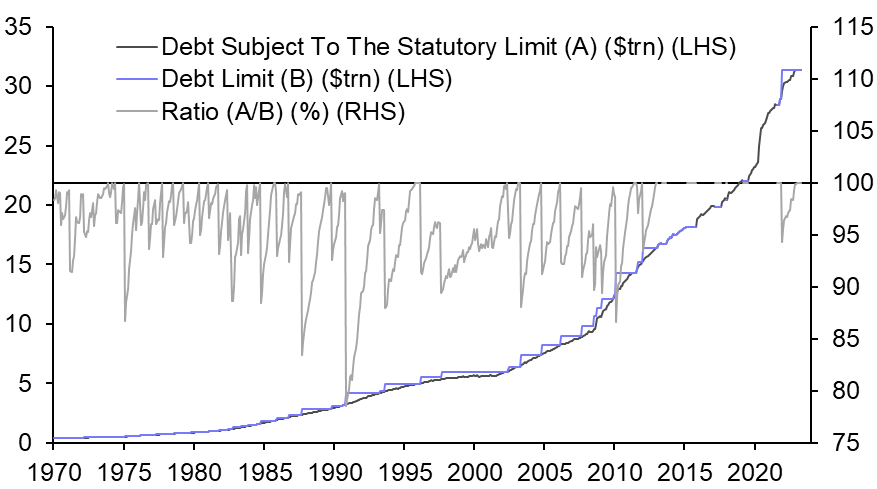

That was Neil Shearing on the idea of a BRICS currency. Mark Williams will be revisiting our 2018 China view in a new report in the coming week or two. So watch out for that. Also Turkey's holding a make or break presidential election this Sunday. That's 14th of May. If you didn't catch our last podcast episode on the economic risks around that vote, you can find it on our dedicated Turkey election coverage page. And I'll link to that in the show notes of this podcast. Now, depending on the reports you read, either progress is being made on reaching an agreement between the White House and congressional leaders to raise the US debt ceiling or both sides remain far apart and a US default is a real risk. To understand what's happening and what it means for markets, I spoke earlier Friday to Deputy Chief US Economist Andrew Hunter and to Jonas Goltermann, who's our Deputy Chief Markets Economist. I started by asking Andrew why the issue has flared up again, and what’s the most likely outcome is this time.

Andrew Hunter

Ever since the midterms last year, when the Republicans won control of the House, I think it seemed pretty likely that with the debt ceiling, there was going to need to be some kind of bipartisan negotiated solution to raise the debt ceiling, most likely involving some kind of modest cuts to government spending. I think that's still the most likely outcome. We know that negotiations are ongoing between President Joe Biden and congressional leaders but I think there's uncertainty, first of all about whether or not they will be able to come to an agreement, how quickly those negotiations will progress. But also over when exactly the deadline to raise the debt ceiling is. So we know from Janet Yellen, the Treasury Secretary, that the Treasury's best guess right now is that the so called x-date is likely to fall at some point in early June, potentially as soon as the first of that month. It's, you know, that's gonna depend in part on things like the strength of quarterly corporate tax receipts, which will start flowing in from early June. But I guess the key point for now is that it seems likely that, you know, the negotiations are probably going to go down to the wire. And I guess the closer that we get to the potential deadline, just the higher the risks really either of a last minute breakdown in negotiations or simply a miscalculation, an accident, if you like, over the exact timing of the deadline.

David Wilder

Do we think that the risks during this current saga are greater than they were during previous flare-ups over the debt ceiling in 2011 and 2013?

Andrew Hunter

I wouldn't necessarily say the risks are higher now than in 2011,2013. But I guess it perhaps just highlights that, you know, this is, I think there is a sense that this is the first time since then that people are, you know, starting to believe that there is a genuine chance – albeit a small chance – that there could be some kind of at least temporary government default. And I think that just highlights the fundamental issue that this is really the first time in basically a decade that we've had the situation of a Democrat in charge of the White House but the Republicans having control, or at least part control, of Congress. Of course, we did have similar situations during the Trump presidency when the Democrats of course controlled the House for the latter half of his term. But I think, you know, with the Democrats, they're sort of conditions for agreeing to raise the debt ceiling was essentially pushing for higher government spending. And I think, generally speaking, that's a lot more politically palatable for everyone. Whereas now, obviously, the Republicans ultimately want big cuts across the board. And that's unsurprisingly proving a lot more difficult

David Wilder

If a deal can't be done what about these workaround ideas that have been batted around? This talk about Treasury issuing perpetual bonds or raising the coupon on Treasuries? There's also, of course, this this long standing idea about issuing a trillion dollar coin. Is this all just pie in the sky thinking or is there anything to them?

Andrew Hunter

I think our general sense, I guess, would probably be to almost reiterate what Janet Yellen and Jerome Powell, the Fed Chair, have been stressing that, you know, there isn't any kind of permanent, costless workaround. Ultimately, the debt ceiling is going to have to be raised. There's a number of different sort of alternative solutions people have talked about. So, first of all, in the in the event that the deadline is reached, there's this idea that the Treasury might be able to essentially prioritise debt repayments over other spending, thereby avoiding the risk of a technical default on US government debt. That's certainly a possibility. But it's likely to be very difficult. And I think at the risk of stating the obvious, it's definitely not a solution and arguably would just be a default by another name. Other people have suggested that the President could essentially just ignore the debt ceiling, perhaps declare it unconstitutional. People talk about the 14th Amendment, which amongst other things states that the US government has to repay its debts. That, though, I think would definitely be subject to a lot of legal uncertainty, immediate legal, challenges from the Republicans, so again not a permanent solution to the crisis. The perhaps the most interesting idea, which repeatedly pops up when we get these debt ceiling episodes, is the idea that the Treasury could use what's a fairly arcane legal authority it has to mint large denomination coins so that this idea of a platinum coin is that the Treasury could essentially create a coin declare its value to be, say, $1tn, $2tn or more. It would then deposit the coin at the Fed, the Fed then credits the Treasury's account with those funds and the Treasury can use those funds to fund its spending and debt obligations. I think a few points to stress though are, first of all it definitely wouldn't be the kind of costless solution that some people seem to suggest. At the end of the day, it would ultimately involve the Treasury essentially assuming control of the money supply which would have pretty serious implications for the Fed’s independence I think. The broader point is that it could potentially risk opening Pandora's box in that if the President and the Treasury decide to mint a platinum coin to avoid a debt ceiling default, who's to say in the future that, a Democratic president, whether it's Joe Biden or someone else, might decide to mint a platinum coin to fund spending on climate change, or perhaps a future Republican administration using a platinum coin to fund tax cuts? I think, given the potentially very serious implications in the long term for inflation, the long term value of the US dollar, I think, there's definitely an argument that going down the road of minting a platinum coin could potentially be at least as damaging in the long run as a temporary default.

David Wilder

Thank you, Andrew. Jonas, I'd like to bring you in now talk about market implications. The headlines this past week have suggested we're on the brink of something like Armageddon, but markets – and leaving aside the CDS market, which we’ll come to – markets have barely budged. What explains this disconnect?

Jonas Goltermann

Yeah, I think you’re right. This has become quite dramatic now, at least in the headlines, but I think the reality is a bit less crazy than that. The way I would think about it is that markets have two broad set of issues to worry about here. One is what I would describe as a technical one, you know, what happens if there are a day or a few days or a few weeks even of missed payments on US debt? How will that feed through mechanically in money markets, affecting cash management systems, collateral, financial markets, and so on? And how do you manage and try to preempt that risk as best possible? And the second issue is, well, there is a risk that the debt ceiling, if it goes on for more than a week or two, that it sets off a wider downturn in sentiment that affects the macro economy, perhaps triggering a recession – something investors are worried about, anyway, already – and how does that broader macro story play out? Now I think the focus to the extent that you see an impact in markets is it's mainly around that first point, the micro issues, where you can see a clear impact, you can see that in the market for short term US debt, one month, three month T-bills yields are considerably higher than they ought to be based on where short term interest rates are. You could see very clear earlier this month when the one month yield jumped, as it moved into that that probable window around the x-date so we’re sort of less than one month out now so therefore, the one month yield has started to reflect that that risk as well. You've seen it maybe in the share prices of some companies that rely a lot on government for the revenues – defence contractors, and the like. They've underperformed the broader market recently. That's probably in part due to worries about how their bottom line will be affected by all this. But I don't think there's that much sign that the broader equity or bond market in the US or elsewhere is particularly worried about the debt ceiling affecting the macro outlook. Equity markets have continued to hold up quite well. Bond markets, we're sort of in this in this range, really, where it's all still about, you know, what's the macro data doing? What's the Fed telling us? How are corporate earnings holding up? You have an additional issue with the US regional banks and so on. But I don't really get the sense that that debt ceiling is driving too much of that. So I would say overall, it's more of a micro concern so far than a macro one. That could certainly change in the coming weeks as we get even closer to the x-date. That was also to some extent the experience in 2011, 2013. The debt ceiling didn't really affect things too much until it really got right down to the wire. And I would I would think it probably plays out similarly this time around. You know, after all that the main takeaway from 2011 and 2013 is that this was a storm in a teacup would you know – they did get it all resolved in the end.

David Wilder

What about the credit default swap market? One year CDS premia have been a focal point for those saying that we are heading for a default? Is that really the case? What is going on with the cost of insuring against a US default? And why is it risen so much?

Jonas Goltermann

The CDS thing is interesting, but I feel like it's a bit the outlier here. Now, as you say, the premium on insuring US debt is considerably higher now than it was in 2011 or 2013 which you could certainly take as a sign that the likelihood of a bad outcome is also higher now, I think there's at least three points to make around that. The first is simply that the US market for US sovereign debt is really very small. According to some recent research that the Fed put out, it's in the order of $10-15bn. Maybe it's a bit more now since they put that paper out but that's still tiny if you compare it to the underlying Treasury market, which is, you know, in the tens of trillions. So in some sense, this is a case of the tail wagging the dog. The second point is that, you know, even the current price, and we're almost at 200 basis points now, I think, or two cents per dollar of face value insured in terms of the US CDS. That's still far lower than what you see in countries that actually have gone through to default on their debt and whether there's been a true sovereign default, think about Argentina or Zambia or what have you. And the third point, maybe the most important one, is that CDS are not a direct measure of default probability. The CDS price reflects both the probability of default, but also the payout in the event of default. So, in the case of corporate bonds, or EM sovereigns, the payout depends on how much bondholders can recover in bankruptcy or debt restructuring. The CDs payout is determined by the auction of the bonds and so the CDs holder gets the face value, typically 100 less the recovery value. But for the US, the default wouldn't in some sense be a real one, at least, that's what we all believe, right? It's just a technical issue where, you know, the US is perfectly capable of paying its debts. And one way or another, I think the common assumption is that payments would eventually resume, even if the Treasury missed a few payments, and that triggered an event of default under the CDS contracts. So the settlement price in the CDS auction for US debt would probably depend mainly on the current market value of US Treasuries. And what's different now from 2011 or 2013 is that a lot of Treasury bonds are trading well below face value, because they were issued when interest rates were lower and therefore coupons on the debt were much smaller. And so as interest rates have gone up over the past couple of years, the market value of Treasuries are trading well below face value, well below par. So that's nothing to do with sort of a risk of default, it's simply that's the correct price for those cash flows at current interest rates. So the thinking is that if there was a CDS auction, the settlement price or recovery value, would be based on very long dated Treasury bonds – those trading in the sort of 60-70 cents on the dollar range – so the CDS payout could be something like 30 or 40 cents on the dollar, which is quite a substantial payout for something you've just paid two cents for. So the implied probability of default here is actually quite low still, even if it looks high. Then it's probably not materially different from the implied probability of default back in 2011 or 2013. So again, this is more of a technical wrinkle – quite an interesting one, I think, personally – but I wouldn't take it necessarily as a sign of impending doom. It's certainly not a good sign but it's probably not as dramatic as it's been out to be.

David Wilder

So you look at the chart, and you think “Oh, my god, the cost of insurance is so high, the US is bound to default!” – more to do with the mechanics of what happens for the settlements of contracts in the event of other credit event. So something of a misleading indicator. You mentioned 2011, 2013 flare ups over this debt ceiling. Is there anything that we can take from the market reaction then that we can apply now?

Jonas Goltermann

So this is something we've looked at closely and imagine that many others have been as well. My takeaway is it's hard to draw very strong conclusions because we only have a handful of examples -- 2011 2013, the main ones. You can look at periods in 2015 or 17, when the debt ceiling was getting close to binding, even though we'd never got as close to the x-date on those occasions. Generally equities didn't do very well around these episodes, especially in 2011. The S&P 500 fell sharply after the US credit rating was downgraded, even though that was actually I believe after the debt ceiling had been raised. Treasury yields fell, as you would expect in that situation. And the dollar actually didn't move too much in either direction. There’s sort of offsetting factors there where risk sentiment worsening tended to support the dollar, but interest rate differential moved against the US at that time. But if you take a step back, though, 2011 was dominated by the eurozone crisis, which was a big negative for equities and it pushed bond yields down pretty much everywhere. 2013 the debt ceiling drama then it coincided with the “taper tantrum”, which pushed US yields much higher and boosted the dollar. I think it's hard to really disentangle the debt ceiling issue or the debt ceiling effect, if you will, from those broader trends. Certainly the eurozone crisis and the “taper tantrum”, they had a much bigger, more lasting effect than the debt ceiling did. So overall, I think the takeaways is, you know, as we get closer to the x-date, you know, maybe we see similar risk off environment, bad for equities, good for bonds, probably for the dollar as well – I'm not sure about that one. It's a bit paradoxical given that this is a US-driven problem that somehow drives up the price of the US bonds. But at the end of the day, unless Congress really, you know, makes this a much bigger mess than what we’ve seen in the past. I feel like this whole episode is going to turn out to be a footnote when we look back at how markets fared in 2023.

David Wilder

That was Jonas Goltermann and Andrew Hunter on this latest tussle over the US debt ceiling. They'll be briefing clients online on Monday 15th May along with Paul Ashworth, our Chief US Economist, so watch out for that. But that's it for this episode. You can find all our coverage, including about the debt ceiling saga, on our website, capitaleconomics.com. And for complete access, including powerful data and charting tools, check out CE Advance. That's our new premium platform. But until next time, goodbye.