My previous overseas client trip was at the height of the Truss-Kwarteng madness and involved flying 7,000 miles to Singapore for meetings dominated by talk of a UK government gone wild. On that note, when the UK came up last week during discussions in North America with clients, the tone was a good deal more sedate.

Jeremy Hunt’s Thursday statement to the House of Commons capped an extraordinary eight weeks in Britain’s political economy, with markets taking his announcement of a £55bn fiscal squeeze largely in their stride.

But this has been a bruising episode for UK institutions – and it has also been an instructive one for other governments.

It’s worth noting from the outset that some of the fiscal squeeze announced last week may never materialise. The Chancellor set himself the objective of stabilising government debt as a share of GDP over a five year horizon (i.e. by 2027-28). But a general election must take place no later than January 2025. As our UK team noted, all of the tightening in the Chancellor’s plans is due to happen after this date.

By this point, there could be a different government in place in the UK – and even if there’s not, there’s a good chance that the UK economy will be in a different position to that forecast by the government’s fiscal watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

So it would be a reasonable bet that some of the fiscal squeeze announced by the Chancellor either doesn’t happen, or comes via different measures enacted by a different government. Even so, it’s notable that the UK is the only major advanced economy that has announced plans to tighten fiscal policy, despite the fact that, like other countries, it is sliding into recession. This raises the obvious questions: why has it done so, and will others follow suit?

From one extreme to the other

The government has justified its budget on the grounds that it must restore fiscal credibility with investors following the debacle of the Truss government’s unfunded tax cuts and the subsequent meltdown in the gilt market. The fiscal approach of PM Liz Truss and her Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, was obviously reckless and a change in course was clearly required. But there’s a risk that the measures announced by Chancellor Hunt may now have swung UK fiscal policy too far in the other direction.

The current government has framed the budget debate around the idea that there is a “fiscal hole” that the government needs to fill. This gives the impression that there is an objectively measurable shortfall in the public finances that must somehow be plugged. But this is seriously misleading. In reality, perceptions about debt sustainability are constantly shifting. What’s needed is a convincing and credible plan to put the public finances on a stable footing over the medium term. There is no single level of the debt ratio or budget deficit that corresponds to this. It will be influenced, among other things, by the performance of the economy and the future path of interest rates. £55bn might be the right number, but there’s a good chance it could be lower if the UK’s economic prospects can be improved.

This brings us to the two factors – beyond the obvious need to provide reassurance over future fiscal discipline – that underpinned last week’s measures: the performance of the UK economy has been dismal and the outlook has soured, and interest rates (and therefore government borrowing costs) have risen.

When it comes to the fiscal outlook, it is nominal (rather than real) GDP that matters. Despite higher inflation, nominal GDP in the UK is still a bit below its pre-COVID trend. That’s due in large part to an exodus from the labour market that has reduced the size of the workforce by around 600,000. More importantly, the OBR now expects some of this weakness to persist. All other things being equal, a smaller economy means lower tax receipts and higher spending on things like social security. The OBR’s judgment is that this will increase the budget deficit by around £40bn.

Meanwhile, higher interest rates have increased the cost of newly-issued debt, and higher inflation has increased the cost of servicing new and existing index-linked government bonds. All other things being equal, this will require the government to run a smaller primary budget deficit (i.e. the deficit excluding debt servicing costs) in order to maintain the previous fiscal trajectory. In the OBR’s latest forecast, government debt servicing costs will be £45.5bn higher in 2027-28 than the 2021-22 outturn.

What not to do

All of this provides a framework for thinking about whether other countries will ultimately have to follow the UK’s lead and announce plans to tighten fiscal policy. Three things matter. The first is the performance (and expected performance) of the economy; the second is changes (and expected future changes) in interest rates and debt servicing costs; and the third is how markets expect fiscal policy to evolve in the future.

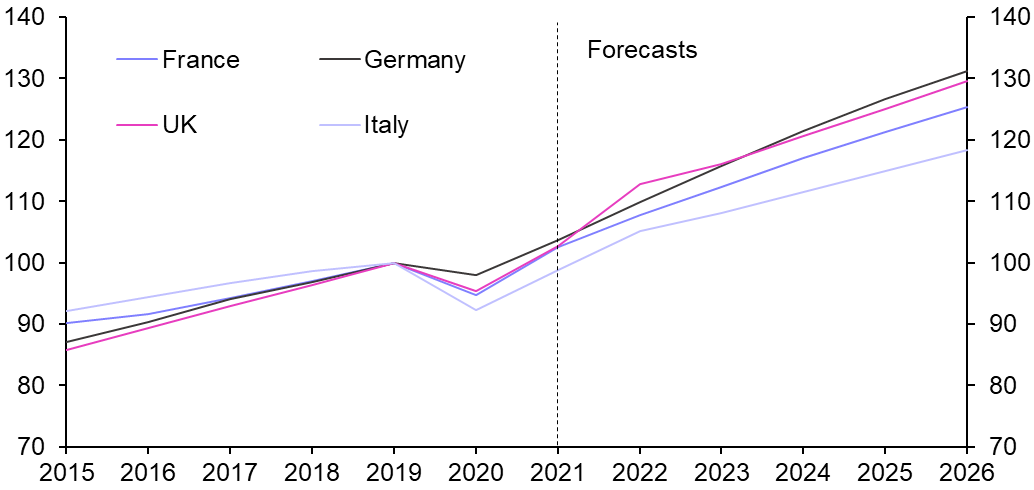

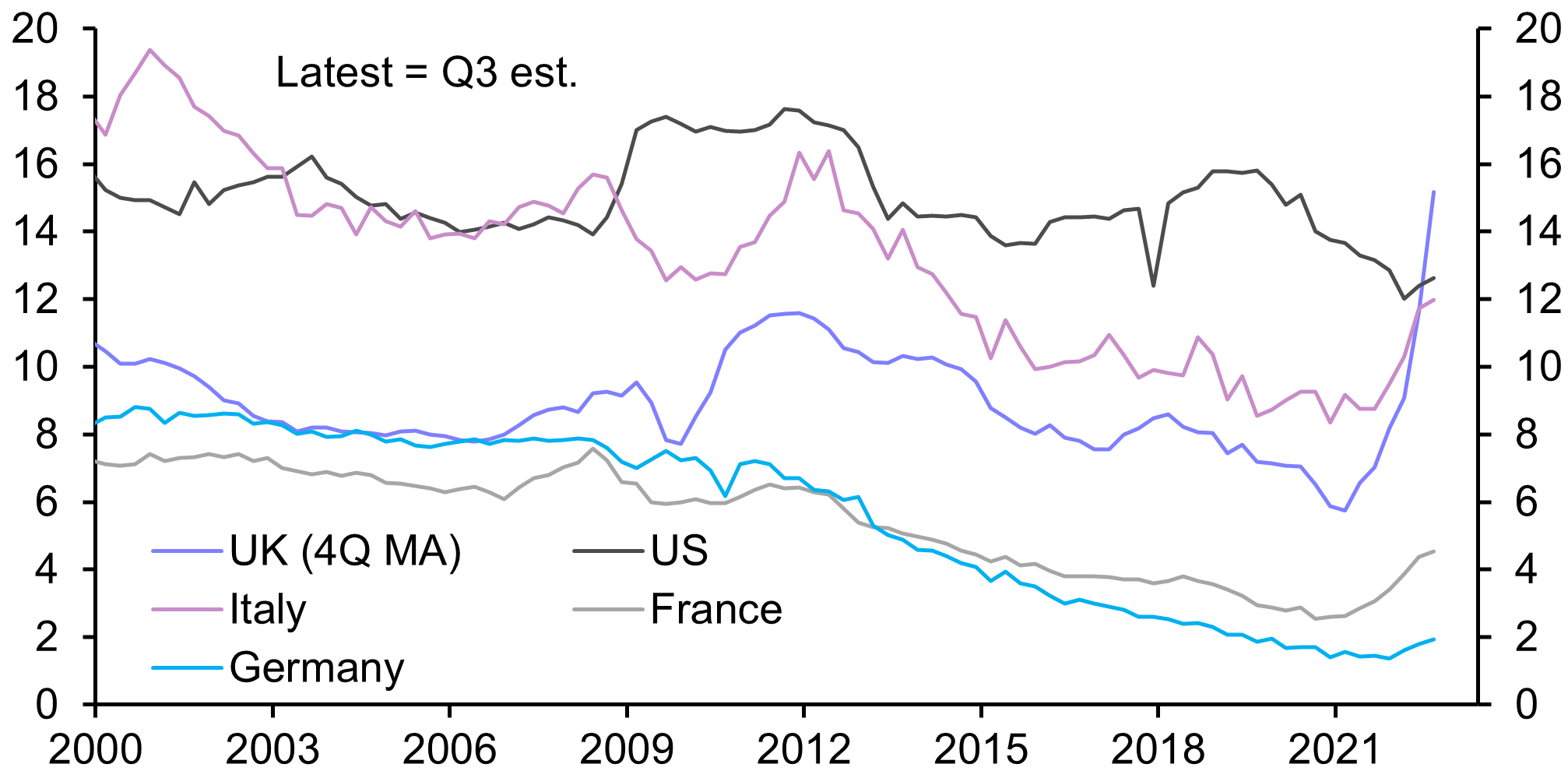

The performance – and expected future performance – in nominal GDP terms of euro-zone economies is similar to that of the UK. But debt servicing costs haven’t risen as far in the euro-zone as they have in the UK, due in part to the fact that the latter issues a relatively large amount of inflation-linked bonds. (See Charts 1 & 2.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sources: IMF, Capital Economics |

Sources: Capital Economics |

Taken together there is nothing in these first two points to suggest that governments in Europe need to announce fiscal tightening measures. The fiscal outlook is much better in the US, where the economic outlook is stronger and the budget deficit has actually improved over the past year.

The third factor is therefore the crucial one. The UK’s current predicament was caused by a perception in markets that the Truss administration had weakened budget discipline and jettisoned the usual constraints on fiscal policy. Not only did it announce large unfunded tax cuts, it also ignored fiscal rules and eschewed OBR oversight. The new government under PM Rishi Sunak has therefore had to persuade markets that it takes seriously the importance of fiscal discipline.

The UK’s experience holds two lessons for other countries. First, there is much less room for fiscal error in a world of rising interest rates. And second, perceptions of fiscal discipline matter and can shift quickly. Other countries in Europe have joined the UK in announcing energy support packages. This includes Italy’s new right-wing government, which will face the first real test of its fiscal credibility this week when it presents its 2023 budget to the European Commission this week.

The reports so far are encouraging. While the government is planning additional spending worth €30bn (1.7% GDP), this looks set to be mostly focused on temporary measures to counter the energy crisis. The measures would also be in line with the medium-term fiscal plan presented by the government a few weeks ago, which envisages a return of the budget deficit to the 3% mandated by EU fiscal rules by 2025.

The UK’s travails illustrate why this is important. Credibility is hard to gain but easy to lose – and winning it back entails significant political and economic costs.

In case you missed it:

- Euro-zone core CPI will remain high until 2025, standing in contrast to what we expect to happen in the US.

- EM debt interest service ratios could rise to 1990s levels next year. This analysis shows which economies are most vulnerable.

- Our FX team discuss the dollar outlook in the latest episode our new podcast.