Hopes for a Fed pivot last week crashed into the reality of hotter-than-expected US inflation data, sending shockwaves through global markets. But while August CPI got the airtime, the more troubling advanced economy data point last week came from the UK labour market.

The US inflation numbers sealed the deal on another 75bp increase in interest rates from the Federal Reserve this week. However, as our Chief US Economist, Paul Ashworth, noted, the 0.6% m/m jump in core prices that rattled markets was driven by two things that tell us little about the future path of inflation.

Shelter prices accounted for half the monthly increase in core CPI, but more timely data on rents suggest those prices will start to moderate in the first half of next year. Furthermore, the health insurance component of CPI, which registered another strong monthly increase in August, should start to ease over the final quarter of this year.

In other words, this release shouldn’t alter anyone’s view about how high rates will have to go. We continue to think the Fed funds rate will peak at 4% in this cycle.

Dropping out

In contrast, UK labour market data for July were altogether more concerning. At first sight, this might seem odd given that the unemployment rate fell to a 48-year low of 3.6%. But this was due in large part to the significant number of workers who have exited the labour market. In the three months to July, 154,000 people dropped out of the labour force or, in the jargon, became economically “inactive”. Compared to the start of the pandemic, inactivity among people aged 16-64 has now increased by 640,000. And if we include workers over the age of 64, inactivity has increased by over 900,000.

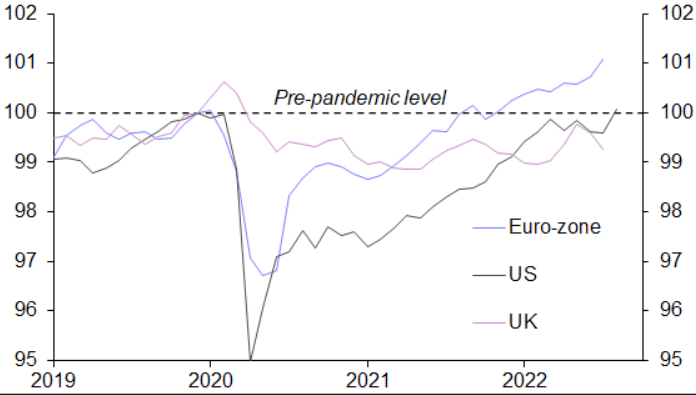

Admittedly, the UK is not the only country to have been hit by labour supply issues – the US has faced similar challenges. But the latest US labour data showed a healthy rebound in participation in August, and the overall size of the US labour force is now back to its pre-pandemic level. In contrast, taking into account changes in net migration (which have been positive), the domestic population (broadly neutral) and inactivity (extremely negative), the UK labour force is now about 1% smaller than it was before the pandemic. What’s more, it’s trending in the wrong direction. (See Chart 1.) The extent of the UK’s labour supply shortfall appears even starker when compared to the euro-zone, where the labour force is now about 1% larger than it was prior to the pandemic.

|

Chart 1: Labour Force (Q4 2019 = 100) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

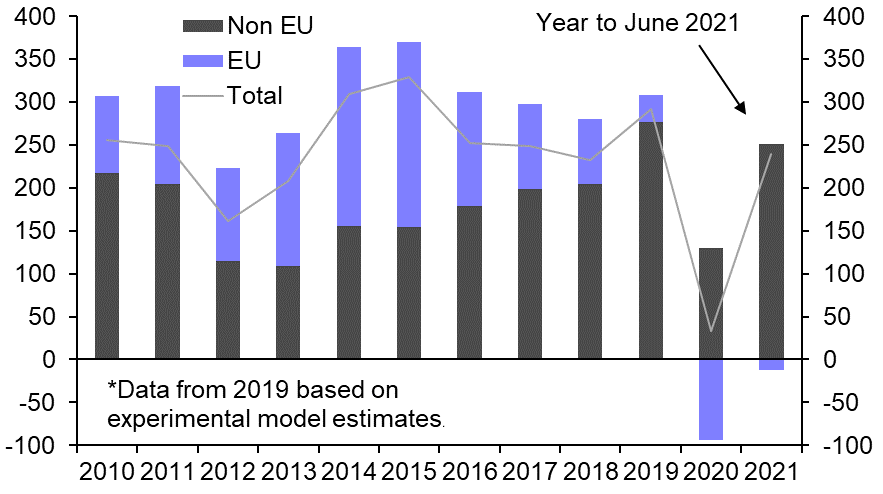

There are two elements to the UK’s labour crunch. First, while net migration has remained positive, it has slowed over the past couple of years. Migration data are released with a long lag and are notoriously difficult to compile. But the latest figures show that in the year to Q2 2021, net migration was a positive 239,000, compared to annual rates of 300-350,000 that were typical prior to the pandemic. (See Chart 2.) The 239,000 figure comprises a net inflow of 251,000 from non-EU countries and a net outflow of 12,000 to the EU. The data are prone to revision, but a post-Brexit slowdown in inward migration from the EU is now becoming evident and the jury’s still out on whether migration from non-EU countries can fully compensate for the shortfall.

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: Capital Economics |

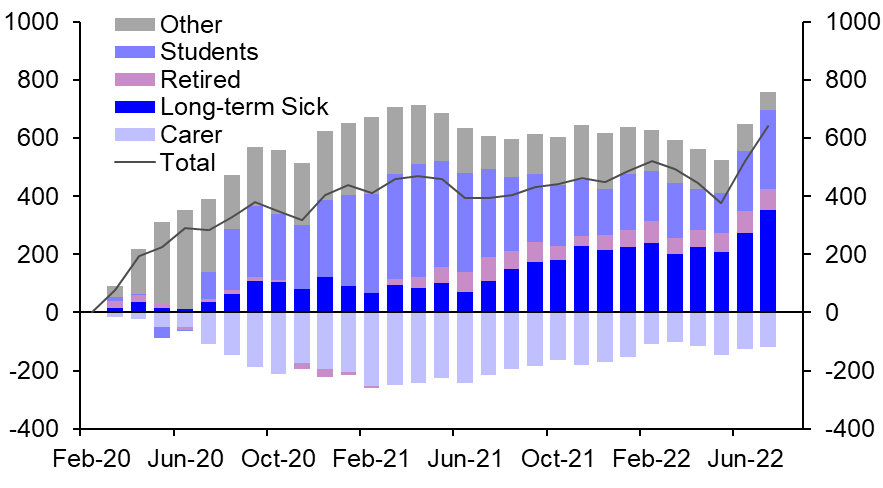

The second part of the labour crunch is the rise in workers exiting the labour market. As Chart 3 shows, there have actually been two waves of this inactivity since 2020. The first was driven by students leaving the labour market in the early days of the pandemic and, until the July data, which may have been affected by wonky seasonal adjustment, had started to reverse. A second wave is now being driven by people unable to work due to long-term sickness. This is not just a long COVID story (plausible estimates suggest it may account for a third of the increase in inactivity due to long-term sickness). It also reflects a failure to treat those with pre-existing health problems during the pandemic and the effects of lengthening NHS waiting lists.

|

Chart 3: UK Labour Market Inactivity (Change from Feb. 2020, ‘000s) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

The net result is a smaller supply of labour and upward pressure on wages. Last week’s data also showed that earnings are now growing at 5.5% y/y. As I’ve noted before, wage growth at these rates is inconsistent with a 2% inflation target when trend productivity growth is now less than 1%.

Dashing for growth

Kwasi Kwarteng, the new Chancellor, has reportedly instructed Treasury officials to “focus entirely” on raising economic growth. This is a laudable objective and an informal target of raising growth to 2.5% a year has apparently been set. We’ll hear more about how the government intends to meet this target in a fiscal statement expected later this week. (We’re holding an online briefing on what to expect after the Bank of England’s September meeting this Thursday – register here to join.) According to media reports, the focus is likely to be on tax cuts and deregulation. But it’s important to keep in mind that the last time the UK economy grew at 2.5% for a sustained period (in the mid-2000s), the labour force was expanding by around 1% a year.

There are cyclical forces at play here that mean that some of the fall in UK labour supply will recover, though we warned back in March that this would take longer than most expected. But structural factors are at work too, and a key task in raising the UK’s growth rate will require reinvigorating the UK’s labour supply. That means getting inactive workers back to work and raising inward migration. Without it, the Chancellor will be left relying on an implausibly large rebound in productivity to meet his growth target.

Inflation data will remain the central concern for policymakers and financial markets over the coming months. But improving the labour supply will not only help ease wage and price pressures – it also holds the key to improving long-run growth prospects.

In case you missed it:

- As the bad economic news piles up in China, James Reilly from our Markets team explained the impact on Chinese financial assets if the People’s Bank of China took the (unlikely, in our view) step of significantly easing policy.

- Senior Global Economist Justin Chaloner looked at the economic implications of an anticipated post-pandemic recovery in tourism in the coming years.

- Shilan Shah, who leads our India coverage, shone a light on Indian purchases of Russian oil.