The Weekly Briefing:

Why is everyone worried about commercial real estate?

A Capital Economics podcast

24th March, 2023

Two weeks into the banking sector turmoil and there are few signs that the panic is ending. David Wilder speaks to Neil Shearing about why investors are still uneasy, whether central banks have made a mistake, and why there's growing focus on commercial property holdings amid the intensifying hunt for the next source of instability.

Plus, wheat consumption has typically grown along with the global population. But that's set to change, according to economist Bradley Saunders. He talks to Caroline Bain about his new report which warns of an unprecedented drop in consumption in the coming years.

- 00:20 Neil Shearing on the banking turmoil and commercial real estate.

- 08:34 Bradley Saunders on the looming fall in wheat consumption.

Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 24th of March. And this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, we'll be hearing how global wheat consumption faces an unprecedented fall. But for now, I'm joined again by Neil Shearing, our Group Chief Economist, who's just back from a week of client meetings in the US and Canada. Hi Neil.

Neil Shearing

Hi David.

David Wilder

It's two weeks to the day since Silicon Valley Bank was closed by regulators and banking shares are still getting beaten up. Where are we amid the great banking sector panic of 2023? We've had armies of bankers, lawyers and regulators trying for a couple of weeks now to put a lid on this. And yet, here we are.

Neil Shearing

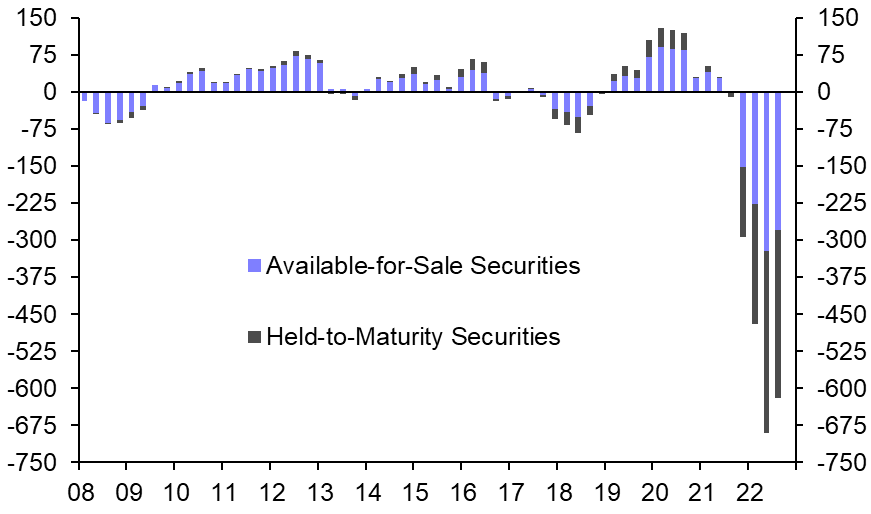

Yes, you're right. Two weeks in and we've moved from problems at SVB and Signature through Credit Suisse and others. We're talking today on Friday afternoon, London time. Bank shares in Europe are down sharply, too. I think we're at the stage of the crisis where there is a recognition – and this came through in client meetings this week, actually – there's a recognition that as interest rates are going up, that is exposing vulnerabilities in the financial system. The problem is that no one's quite sure where the next vulnerabilities are going to emerge. So the hunt is on for the next shoe to drop as it were. And clearly a lot of focus is on banks and bank risks. Not necessarily systemic risks, but individual institutions that might be running into trouble or have particular kinds of strains or problems on their balance sheets. I think that's the stage of the crisis where we are at. People are trying to work through what the next shoe to drop might be. What are the implications of higher rates in the financial system? What vulnerabilities might this expose? And when might those emerge?

David Wilder

So we're talking about vulnerabilities in the banking system, but it's not just about the banking system, is it. This month is the 50th anniversary of Bear Stearns’ failure. And that was midway through the Global Financial Crisis, which began in the US housing market. This time, there seems to be a lot of focus on commercial property rather than on housing. Why is that considered the potential pain point to watch?

Neil Shearing

Well, it's a long and complicated story. But the essence of it is that it's an issue in the US in particular, and it's because small and mid-tier banks in the US do a lot of the lending to commercial real estate. So about 70% of lending to US commercial real estate comes from the small and mid-tier banks. Now, this isn't necessarily because those banks are experiencing the same problems as SVB, for example. It's more to do with the fact that as interest rates have gone up, returns on short-dated securities have gone up too. And that has meant that there's been a shift in deposits out of the banking system and into money market mutual funds in the US. So one way to stem the outflow of deposits from banks to money market mutual funds would be for banks to raise interest rates on their deposits, but that will obviously squeeze their profits. And what that means is that when loans come up for renewal and need to be rolled over, interest rates are going to go up on those so credit conditions, lending conditions, to commercial real estate, I think are going to tighten. They have tightened, they will tighten further. And that's what's at the heart of the concerns about commercial real estate in the US. This is a market where moves in price tend to happen very slowly. It's an illiquid market. It's not like stock market where prices are bank shares are up 10% one day and down 20% the next. This is much more of a slow burn issue. But I think if we're thinking about next shoes to drop, commercial real estate is a place that looms large.

David Wilder

I wanted to talk about what's happening with credit conditions. Jerome Powell talked on Wednesday after the FOMC statement came out about bank stress causing, I think he called it “significant tightening in credit conditions”. And we just had weak durable goods orders for February from the US. So that's even before the panic of recent weeks. Simon MacAdam from our global team had this report a few weeks ago. It talked about how most of the hit from monetary tightening is still to come. Since then, we've had more rate hikes from the ECB and the Fed and the Bank of England – all amid this wave of financial instability. Putting all of this together, does this mean that what was going to be a bad economic situation is going to be made worse? Are these banks going from making a mistake in acting too slowly on inflation to raising rates incautiously?

Neil Shearing

I think there's certainly a risk and this is something we've talked about before, isn't it? Because the old ways of forecasting inflation and thinking about inflation have shown to be flawed, banks, central banks, forecasts of inflation are not necessarily as reliable as they once were. They're putting more weight on actual inflation. And that means that by definition, given that inflation is a lagging indicator, they were almost certainly going to overtighten. And I think some of the problems that we are seeing emerge in the financial system are a symptom of that. You’re right the meetings that we've had over the past week or so, the main message is still that banks are focused primarily on inflation concerns and getting on top of inflation. They’re putting more weight on that. They’re acknowledging risks in the financial sector. But we've had a series of what you might call dovish hikes, in other words, acknowledging risks in the financial sector, reaffirming their roles as lender of last resort and commitment to providing liquidity to any institutions that need that liquidity. But, nonetheless, using interest rates as the main policy lever to tackle inflation and getting those up. I think the problem is, though, is that monetary policy, as you alluded to works with lag. We know that and you're right, we put a piece out a couple of weeks, even before this banking stress emerged, looking at how much of the effects of previous monetary tightening have yet to feed through to the real economy. And we concluded that perhaps more than half has yet to to be felt in the real economy. If you look at things like credit impulses, financial conditions, indices, I think there's more pain to come on the GDP front, on the activity front. That's even before the stress of the last few days or so. So, yes, we had recessions in in almost all of the major advanced economies for this year. I think the risks are that those recessions turn out to be a bit deeper perhaps.

David Wilder

And just coming back to commercial property, our property team is going to be briefing clients this coming Tuesday on the risks all around the sector. Even before the panic of recently exposed a warning of a double-digit percentage fall in valuations this year. With this tightening of credit conditions, are we going to see a harder fall? If so does that reverberate back through the financial system? I know we push back against talk about this being a repeat of the Global Financial Crisis. But is this all getting a whiff of crisis at least.

Neil Shearing

I think you're right there is a whiff of crisis here. And in particular, the feedback loop from property to the banking system to the real economy. And there is, I think, a risk of a vicious cycle developing there by which banks come under pressure, particularly these small and mid-tier banks in the US, they come under pressure, credit conditions start to tighten for commercial property, therefore, and as that happens, loan losses in that sector start to increase, banks come under renewed pressure as a result, and they tighten credit conditions even further. And that puts a renewed pressure on the commercial real estate sector and also the wider economy’s credit conditions tightened so that you get this adverse, almost doom loop in some senses developing now. I don't think we're there. It's not certainly not our base-case scenario. But it's not difficult to see how something like that could develop in a worse case scenario. See, I think that there's certainly a whiff of crisis. It’s certainly easy to envisage how this could develop in ways that are far more adverse than it is in our central forecast at the moment. Like I say, we're expecting recessions in most of the advanced economies. By and large, they're pretty mild, certainly, in the case of the US. We’ve got peak to trough falls for GDP of about 1% or so, which would be mild by past standards. But I think there are downside risks to that forecast growing,

David Wilder

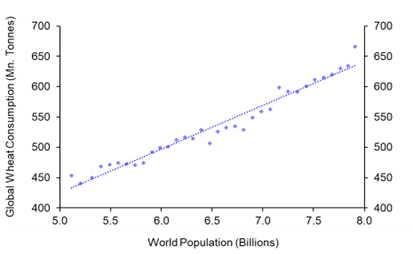

That was Neil Shearing on the banking panic and the risks around commercial real estate. Now, wheat is the world's second most consumed grain, it accounts for 20% of global calorie intake, and that's expected to grow. Consumption growth has been typically linked to population growth. more mouths to feed means more demand for bread and more demand for animal feed. But that's all set to change, says Bradley Saunders has just completed an in-depth study which looks at long term consumption trends. And Brady concludes that the wheat market is facing an unprecedented shift as well population patterns change. He recently sat down with Caroline Bain, our Chief Commodities Economist, to explain what's wrong with some of the current assumptions about wheat demand growth. Their conversation starts with Brad setting the scene

Bradley Saunders

We've seen consumption fall in the past due to supply impacts. In fact, global consumption fell last year, given the Russian invasion of Ukraine and droughts and key producers, such as the US and Argentina. But looking forward, we think that this is going to change, we think that consumption could fall in future decades, not because of impacts on the supply side, because of outright contractions in demand. Although we expect consumption to sort of continue rising at its its current average rate of about one and a half percentage [point] per year throughout this decade and the next, we do think the further out in the 2040s and beyond that, we could see a long-run trend of falling consumption, though we think this would mostly be driven by demographic shifts. And this is really significant. The growth in the global population has always come alongside greater wheat demand. So for the global population to continue to grow, but for global wheat consumption to peak and then enter a period of long run decline, it's certainly unheard of.

Caroline Bain

You say demographics mean that wheat consumption will eventually peak. But don't we have projections of the world's population that wouldn't be continuing to grow in the 2040s? I struggled to get my head around how you can have these seemingly contradictory ideas. Surely, if you've got more mouths to feed, that's going to be more wheat consumption. That's the way it's been in the past.

Bradley Saunders

That's absolutely true. The UN, which we have taken the forecast off when writing our report, does predict the world population to be growing in the 2040s. But it's really important we consider where this population growth is coming rather than looking solely at the total figure. This is because wheat consumption isn't uniform across economies. Just like any economic good, its demand depends both on people's incomes and their preferences. Now, preferences in this case we took to mean as sort of the culture of the economy and its cuisine as is often determined by its geography and its trade history. So for instance, a European consumes more than double the volume of wheat consumed by a Chinese person in a given year. It's hardly surprising, intuitively, given the prevalence of wheat and European cuisine, so we have bread and pasta and cereal and so on, compared to Chinese cuisines, which has very little. And so with all of this in mind, the negative impact on global wheat consumption from one less European consumer would outweigh the positive impact from two new Chinese consumers.

Caroline Bain

So just to be clear here, what you're saying is that growth in global population will not necessarily lead to growth in global wheat consumption, because where the growth in population is, is in countries that do not have wheat based diets essentially.

Bradley Saunders

Exactly that. And that's really as I mentioned, when we consider preferences. That’s before we even move on to considering differences in income. Now, economists generally consider wheat to be a staple agricultural. So by that we mean it's consumed widely and regularly in many diets. So human consumption of wheat is relatively income inelastic. That's not to say that income can't affect the consumption whatsoever. We have to appreciate that wheat isn't only used for human consumption, it's also used as an input into animal feed. And although consumption of wheat may not depend on incomes because, as mentioned, it's a staple agricultural, we do see in the data that as economies develop and incomes increase, demand for meat does increase. And so by having greater demand for meat, you require greater supply, which means that there is greater demand for animal feed. And so in this sense, incomes do determine wheat consumption. And so this is another factor which can explain sort of regional differences in wheat consumption, as I say both preferences and incomes. And so going back to the original question, once we consider these differences in preferences and incomes between economies, we realise it's far more the patterns of regional population growth which will determine global wheat consumption going forward, rather than the total population figure. And so, in particular, the UN has the European population declining from the early 2030s, which should deal quite a significant blow to global wheat consumption given how large of a share Europe accounts for. And although as you rightly say the world population is forecast to continue to grow. This growth is concentrated in other regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa, which not only do not typically have wheat based cuisines, we also don't believe that they're likely to reach a sufficient level of development during our forecast window at which this greater consumption of meats and import of foreign cuisine possibly has enough of an impact to give a significant boost to wheat consumption and, and certainly not enough of one to outweighed the negative impacts of the falling European population.

Caroline Bain

I don't know if this is significant Bradley but one thing I'm quite aware of living in Europe is the growth of vegetarianism and veganism. Is that something that you have considered in your forecast in terms of lower meat consumption in Europe might be an additional factor pulling down the European consumption figure?

Bradley Saunders

Yeah, no, definitely. I mean, consumption patterns are prone to change for numerous reasons. And these can be really hard to predict. For instance, in China, which has traditionally been a large tea consumer, an influx of large coffee brands, such as Starbucks, and the increasing popularity of Western coffee shop culture, has seen coffee consumption take off in the past couple of decades. I mean, in per capita terms, it's still fairly low at a global level, but it's still a point to consider these sorts of idiosyncratic changes are very hard to account for when forecasting. And so in the context of this report, we have had to consider in certain economies, which could contribute largely to the global figure, these sorts of specific factors. So as you mentioned, in advanced economies, there can be the economic capability to decide to shift towards vegetarianism or veganism, and in other countries there can be a cultural factor. So in the case of India, we had to appreciate the fact that, although it is a country which is traditionally a large wheat consumer in terms of its cuisine, it's also a country which around 35% of its population are vegetarian or vegan and given this is largely on religious grounds, this is something that really wouldn't change as the country develops in future and so, in this case, although we see economic development, we may not see those effects on wheat consumption via the meat demand channel, we mentioned earlier,

Caroline Bain

I'm conscious that there are always risks to to forecasting, where would you say the the main risks lie to your wheat forecasts?

Bradley Saunders

No, definitely. On the demand side we have these shifts in in culture, which can be very idiosyncratic as I mentioned earlier, but of course, we've not even acknowledged supply so risks we've had to consider one of which is climate change. Now wheat is a fairly resilient crop. It can grow quite sufficiently in a wide range of temperatures and altitudes. And so its exposure to higher global temperatures maybe isn't as significant as some other more climate sensitive crops. But nonetheless, as we've seen, in the past year, we've had droughts in the US and parts of Europe, Latin America, the increased prevalence of extreme weather events can have a notable impact on wheat supply. If global temperatures were to rise at a faster pace than is currently our base case, or, conversely, climate change adaptation strategies – so GM crops and things like that – become more easily accessible, then globe wheat spike could fluctuate quite considerably from our current forecast. And this would have a real impact on market dynamics and of course, prices. And of course, on the supply side, there are also political factors to consider. So, as has happened in the last year, we had the Russian invasion of Ukraine and this is the reminder to some of the risks of relying on one or two suppliers for a commodity, particularly when it's something like a staple agricultural, it leads to worries of food insecurity. That's happened a lot in the Middle East and North Africa. In the past, it was one of the main factors driving the Arab Spring, about a decade ago, and these worries of food insecurity have led to North African and Middle Eastern economies stepping up subsidies for domestic wheat production and things like that. And if that were to continue, if there was sort of a legacy of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we could see more and more supply coming into the global market from these economies, which currently don't produce that much, which could lead to quite significant changes to our long run price forecasts. If that were the case,

Caroline Bain

You’ve touched on it just just now, Brad, what does all this mean for our wheat price forecast?

Bradley Saunders

Yeah, so I'm afraid to say for everyone who's listening who's probably tired of paying considerably more for a loaf of bread at the minute, we are probably looking at rising real agricultural prices going forward. Of course, in the very near term, consumers are feeling the impacts from the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the droughts that you mentioned earlier. And so, in the next couple of years, prices should fall back in real terms. But looking further ahead, we do think that prices should rise throughout the next couple of decades. We, we think the risk from climate change could feed into a higher structural risk premium. And there also may be partly a higher risk premium due to the potential for supply disruptions from war or other political discourse, as mentioned a moment ago. But as we move into the 2040s and we have this slowdown in growth of demand and eventual peak in consumption and contraction thereafter due to this fall in the European population, as well as sort of assuming that climate change adaptation strategies may come on more in that, in that period of time, we do think that prices will fall back down again slightly in real terms. But on the whole, they will stay far above today's levels, as is the case with most agricultural commodities.

David Wilder

And that's it for this week. You can find Brad's report on the podcast page along with links to our analysis all about the banking panic, commercial real estate and much more. For complete access to all our insight check out CE Advance, our new premium platform. But until next week, goodbye.