One explanation for the greenback’s weakness stands out

In what’s been, at least by the standards of 2020, a relatively quiet summer period for financial markets, one question has stood out: what’s behind the weakness of the US dollar?

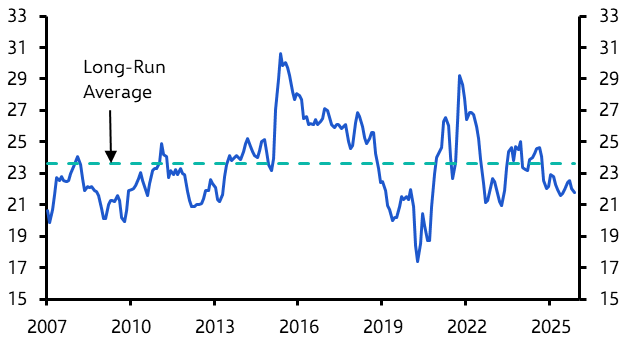

In fact, when viewed over a long run, the dollar is not particularly weak. As Chart 1 shows, in trade-weighted terms the US currency is actually trading well above its ten-year average.

Chart 1: Trade-Weighted Dollar Index (Jan 2006 = 100)

Even so, it remains the case that the dollar fell by about 5% in trade-weighted terms in July. While that may not sound like much, it was the largest monthly fall in over a decade. What’s more, the context in which the dollar has weakened over the past month has been unusual.

In the past, the dollar has tended to strengthen in periods of rising risk aversion – for example when concerns about the outlook for the global economy have triggered a flight to safe assets – and weaken in periods of increased risk appetite. One consequence is that moves in the dollar have typically been inversely correlated with moves in the stock market, as has been the case for most of this year.

Yet the drop in the dollar over the second half of July came alongside a small fall in most stock markets and against a backdrop of increased concerns about the post-virus recovery.

What is going on? Several theories have been advanced. One is that the weakness of the dollar is the flip side of a stronger euro, which has benefitted from signs that European policymakers are finally getting their act together. Yet the dollar has not just weakened against the euro – it has weakened against other currencies too.

Another explanation that has been put forward is that massive money-printing by the Fed, combined with deepening political dysfunction at home and a growing strategic rivalry with China abroad, has reduced the allure of the dollar and hastened its demise as the world’s reserve currency. Yet this is wildly overdone – there is currently no credible alternative to the dollar as a reserve currency. And by setting back the internationalisation of the renminbi, which is the only plausible rival to the dollar over the long run, the growing strains between the US and China may actually strengthen the dollar’s position as the world’s reserve currency.

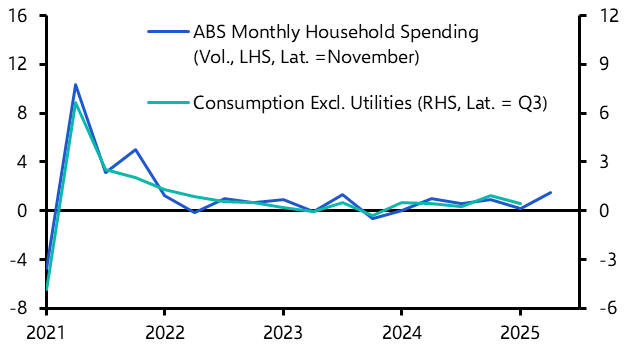

Instead, a more intriguing explanation for the recent dip in the dollar lies in what’s been happening to the inflation expectations that are baked into bond markets. Inflation expectations in most countries have risen over the past month or so, but the rise has been particularly marked in the US. (See Chart 2.) Furthermore, since nominal yields on US Treasuries have remained steady, the rise in inflation expectations has caused a corresponding drop in US real yields. This drop in real yields may in turn have weighed on the dollar.

Chart 2: 5-Year Bond Market Inflation Compensation (pp)

This begs the question: why has the rise in inflation expectations not come alongside a rally in the stock market? After all, a rise in inflation expectations should signal greater optimism about economic growth, which in turn should support equity prices.

One answer may be that the rise in inflation expectations could reflect speculation about a regime shift in the US that tolerates – or indeed targets – higher inflation. Admittedly, Jerome Powell made no mention of this in his remarks following last week’s FOMC meeting. But this hasn’t stopped other officials at the Fed from talking regularly about something akin to an average inflation targeting regime – allowing inflation to rise above its target a bit before tightening. We suspect that the Fed’s year-long review of monetary policy, which has been delayed by the pandemic but should conclude soon, could lay the groundwork for such a shift.

Rationalising short-term movements in currency markets is often a mug’s game. However, the prospect of higher inflation in the US compared to its peers may be among the more compelling reasons for investors to bet against the dollar over the long run.

In case you missed it:

- Our property team are launching a new series of working examining the future for residential and commercial property after the pandemic – read more here.

- Our Senior Markets Economist, Jonas Goltermann, examines what a shift towards the greater of financial repression would mean for markets in emerging economies.

- Finally, a reminder that we are upgrading our email delivery system over the next week. There is a small chance that this results in our emails not reaching you if your corporate IT system doesn’t recognise us after the switch. To make sure that doesn’t happen, please provide this information to you IT department.