In August 2021, while Jerome Powell was arguing in his COVID-compliant Jackson Hole address that inflation’s resurgence was “transitory”, emerging market central banks across Emerging Europe and Latin America were taking no chances and raising rates.

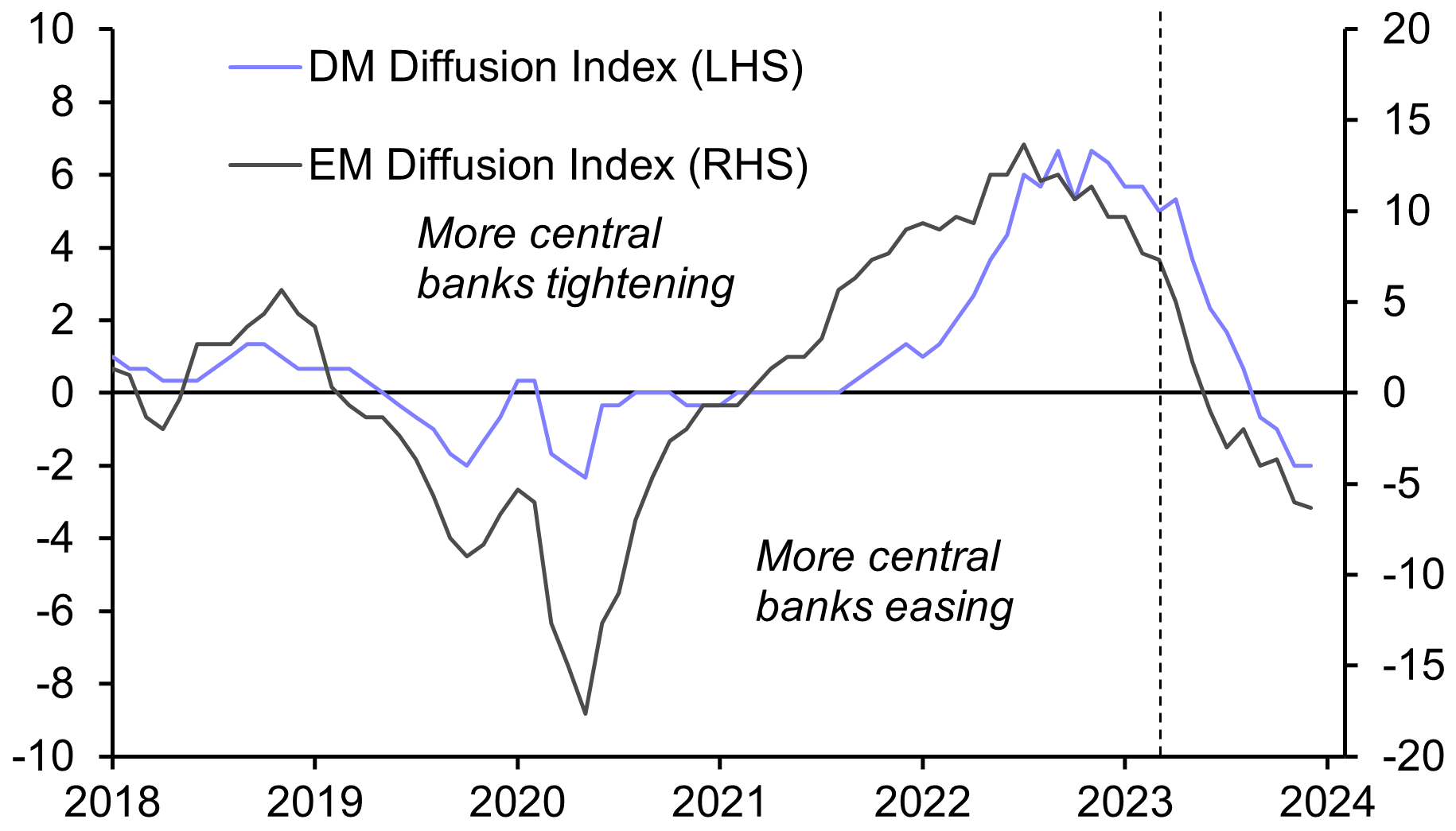

EM central banks may have historically followed the Fed, hiking interest rates when it tightened policy and cutting them when it loosened. But many of these banks have led rather than followed in this cycle. They were among the first to begin raising rates in late-2021. (See Chart 1). And while investors are still debating how much further interest rates in the US (and Europe) will have to rise, many EM central banks have already brought their rate hiking cycles to an end.

Policymakers in Romania and Peru signalled they were done with rate hikes at their meetings last week, and we think the Reserve Bank of India (which also met last week) has finished tightening too. Although Mexico’s central bank did spring a surprise with a larger-than-expected hike and hawkish statement at its meeting last Thursday, we think that there will only be one more increase in the cycle there.

|

Chart 1: EM & DM Diffusion Indices |

|

|

| Sources: Central Banks, Various Academic Studies, CE |

‘Shoot first’ policy

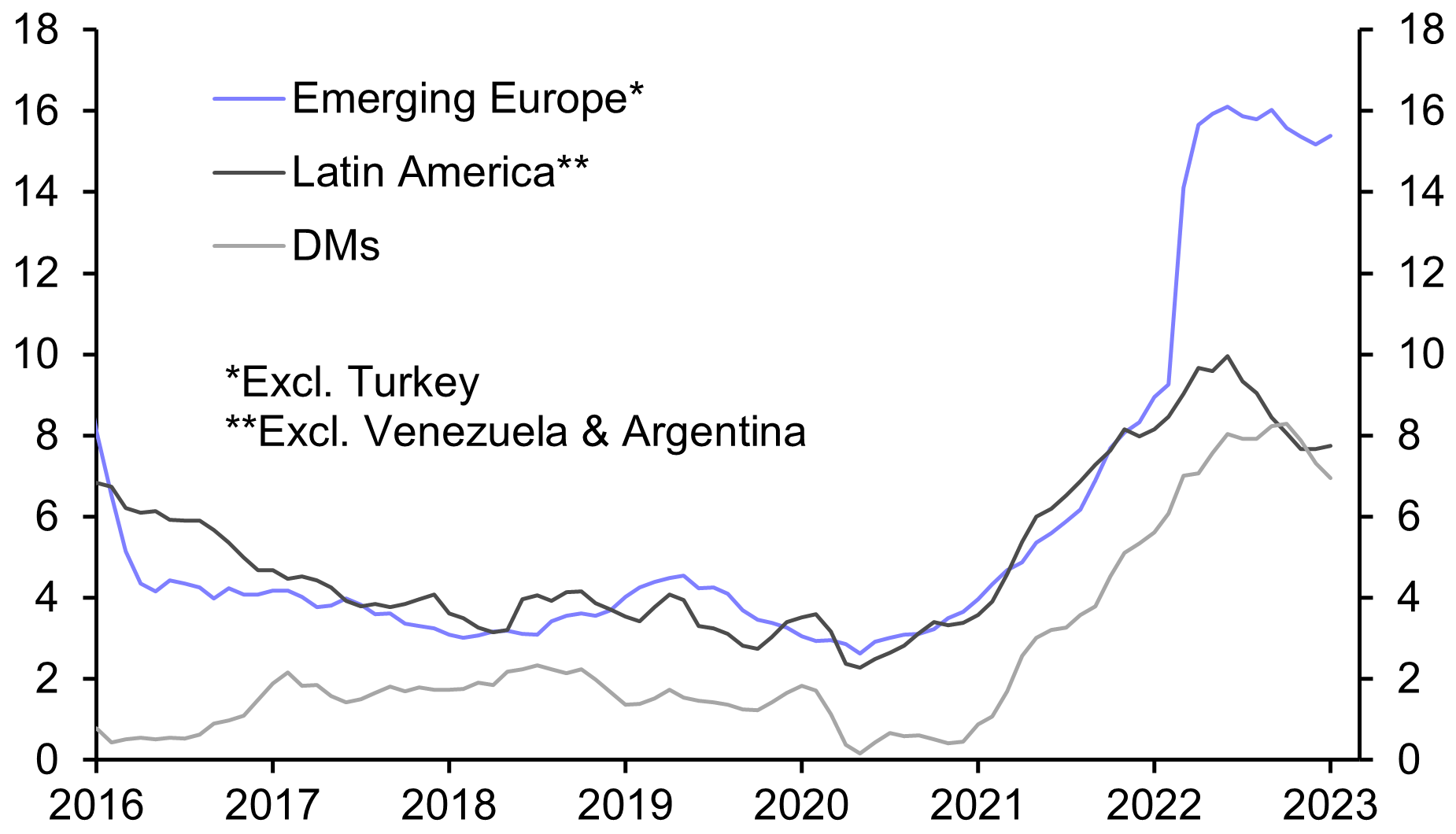

The different approach among central banks in Latin America and Eastern Europe is partly explained by the fact that their surge in inflation over the past year or so has been far greater than that experienced in the US and euro-zone. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: Headline Consumer Price Inflation (%) |

|

|

| Sources: Central Banks, Various Academic Studies, CE |

But these policymakers didn’t demur with their advanced economy peers in finding out whether the inflation shock was “transitory”. They erred on the side of caution and hiked interest rates anyway. Inflation expectations in these economies are less well anchored, meaning that central banks have less margin for error.

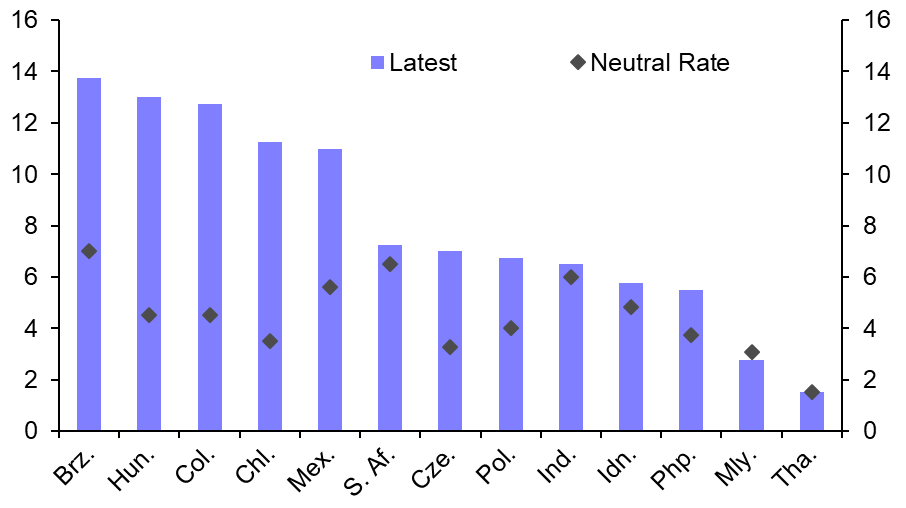

But their reluctance to wait and see also reflects a different attitude towards inflation among these policymakers. Central bankers in Emerging Europe and Latin America came of age in the era of rapid EM inflation during the 1980s and 1990s. They have seen first-hand what happens when the inflation genie is let out of the bottle. Accordingly, they hiked early and they hiked aggressively. Interest rates in most EMs outside of Asia have been raised to well above our estimate of their neutral level.(See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: Policy Interest Rates (%) |

|

|

| Sources: Central Banks, Various Academic Studies, CE |

The Asian exception

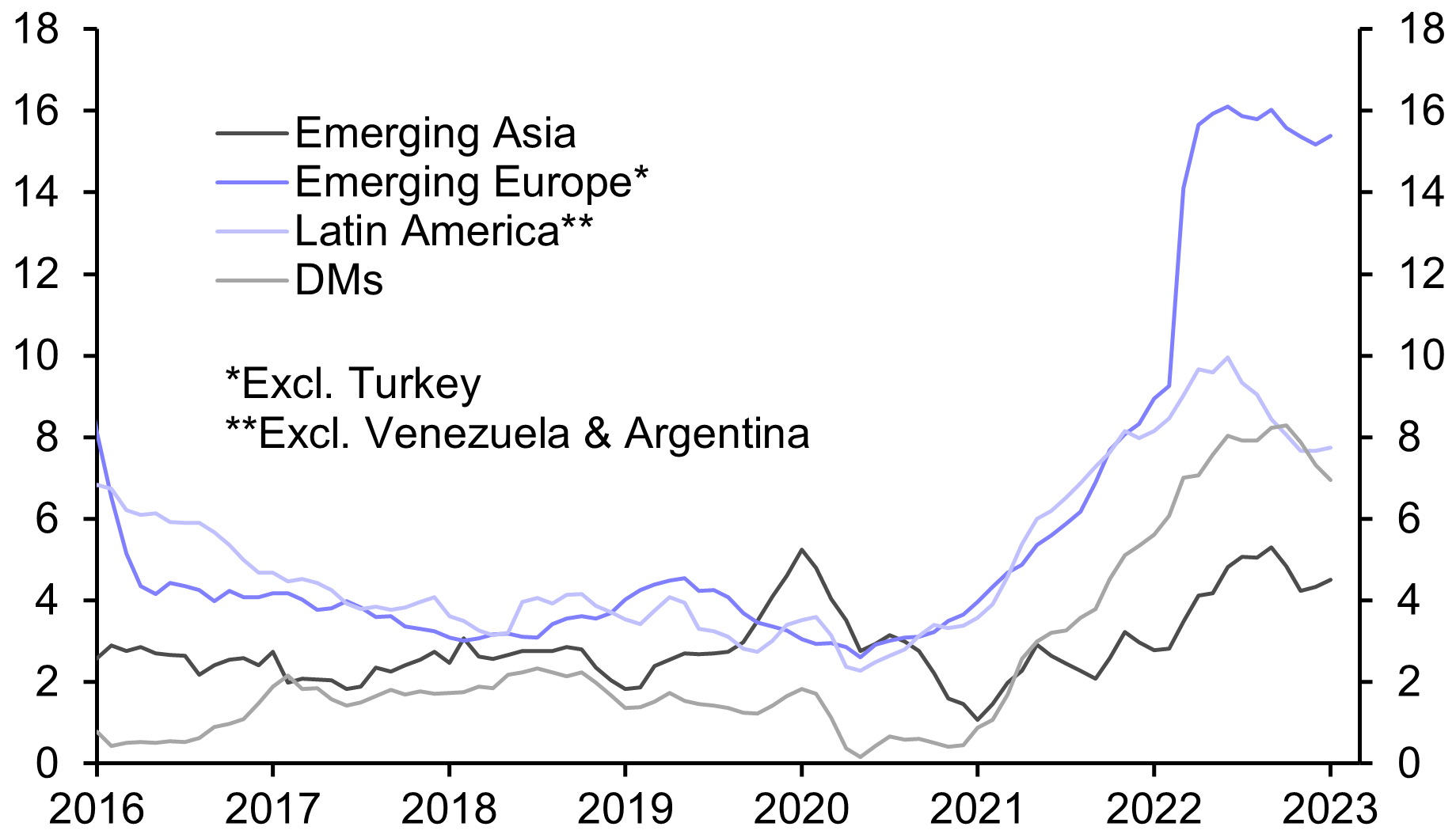

Asia has had a different inflation experience. Its economies have been helped by domestic conditions (including stronger harvests), which have meant they have not experienced the same spikes in food inflation seen in Europe or the US.

Energy subsidies have also shielded many households in Asia from the worst of the surge in global oil and natural gas prices. And local manufacturers appear to have kept domestic markets in Asia well supplied, thus insulating economies in the region from pandemic-related goods shortages. Add in structural forces such as high savings and investment rates that act to suppress inflation in some Asian economies and the result has been that both headline and core CPI in the region have been much lower than in the US or Europe. (See Chart 4.) Accordingly, there has been less pressure on these central banks to tighten through this cycle.

|

Chart 4: Headline Consumer Price Inflation (%) |

|

|

| Sources: Central Banks, Various Academic Studies, CE |

The cycle turns

Economic growth is now slowing across the emerging world, and several EMs are experiencing mild recessions. But the major EMs have come through this tightening cycle without experiencing substantial financial stress. This has confounded those analysts who predicted a wave of EM crises a year or so ago but, as we’ve argued throughout this cycle, balance sheets in emerging economies are better able to withstand US policy tightening these days and banks are in better shape. So while economies are under pressure, they are not collapsing.

EM central banks will also probably be the first to turn towards interest rate cuts. Some, including those in Korea, Chile and Czechia will probably do so by the middle of this year. And given the backdrop of falling inflation and weaker growth, we’re likely to be in a broad-based EM easing cycle towards the end of this year.

The size of the US economy – and the centrality of the dollar within the global financial system – means that markets will necessarily focus on the actions of the Fed. But the early and aggressive action of policymakers in emerging economies during this cycle has flown under the radar. As the debate shifts from tightening to loosening, several EM central banks could once again lead the way.

In case you missed it:

- Our US Economics team explained why January’s stunning jobs report doesn’t change the fundamental story about a US economic slowdown ending in recession

- Tortured debt restructuring negotiations could get even more adversarial in a fracturing global economy, warns Deputy Chief EM Economist Jason Tuvey.

- I discussed EMs in our latest podcast episode, which this week also includes analysis of the Adani Group crisis and how it could expose Indian banking system vulnerabilities.